Willie Thrower made history for the Chicago Bears as the modern NFL’s 1st Black QB. 70 years later, his family hopes for recognition.

Willie #Willie

Willie Thrower lived his life as a footnote in the history books of one of professional football’s most storied franchises.

A quarterback whose “name is synonymous with his skill as a player,” as the Pittsburgh Courier declared in 1953, Thrower was the first Black quarterback to play at a Big Ten school and in the modern NFL. He made his professional debut for the Chicago Bears on Oct. 18, 1953, with less than five minutes left in a game against the San Francisco 49ers at Wrigley Field — six years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

Thrower relieved future Hall of Famer George Blanda with the Bears trailing 35-21. He completed 3 of 8 passes for 27 yards with an interception before being removed. Coach George Halas explained the decision the next day, according to the Chicago Defender: “We had a particular play we wanted to call next and Thrower has not learned all of our offenses. He just didn’t know the play.” The Bears lost 35-28.

The game was Thrower’s lone NFL appearance after notable high school and college careers. Now, 70 years later and 21 years after his death, his family and historians want people to know his name — and his story.

Overcoming obstacles

Born in 1930 in New Kensington, Pa., outside Pittsburgh, Thrower was a highly touted and skilled high school player. He led New Kensington to two Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League (WPIAL) championships and a runner-up finish for the state title.

In 1946 the team was invited to play in the Peanut Bowl, an annual showcase of top high school teams at the Orange Bowl stadium in Miami.

“Because of the Jim Crow laws there, they told New Kensington High School’s coach (he) could bring (the) white players, but they would have to leave the two Black players — Willie Thrower and Flint Green — behind,” recounted George Guido, a retired journalist and New Kensington historian.

According to Guido, Thrower’s teammates declined the invitation because everyone wasn’t allowed to attend. It was then Thrower started to get national recognition. He was voted an All-American his senior year and named to the Pennsylvania All-State team. As part of the All-America honor, Thrower was invited to play in a national all-star game for high school players in Corpus Christi, Texas.

“He was named captain and then the people down there found out he was Black,” Guido said. “And they said not only are you not captain anymore, you can’t come and play because Texas had a law against interracial sports teams playing against each other.”

It wouldn’t be the last time Thrower’s race would become an obstacle to his football aspirations.

“My dad had a lot of offers from the South,” Thrower’s son Melvin said. “He had scholarship (offers) from Georgia, Miami, Kentucky … but once they found out he was Black, they didn’t offer him the scholarship. Once they realized his name and who he was and his ethnicity, that’s when they pulled the scholarship and that’s why my dad went up North.”

From 1949-52, Thrower was a backup quarterback at Michigan State, which joined the Big Ten in 1950 (though the Spartans continued to play football as an independent until 1953). He was one of four Black players on the team along with safety Jim Ellis, halfback Leroy Bolden and end Ellis Duckett, who was named to the Chicago Tribune All-America team in 1951.

Thrower didn’t see much playing time at Michigan State, but in the second-to-last game of the Spartans’ 1952 national championship season, quarterback Tom Yewcic was injured and Thrower was called upon to finish the game against No. 6 Notre Dame.

Entering the game with the host Spartans holding a tight 7-3 lead, Thrower helmed two touchdown drives in a 21-3 victory that extended the nation’s longest winning streak to 23 games.

“My dad had an arm,” Melvin said. “While he was at Michigan State, the coach would have him line up at the 40-yard line and throw the ball down the field. That’s how they would practice their punt returns and kick returns.”

Though only 5-foot-11 and 170 pounds, Thrower is said to have had large hands and incredible arm strength, able to throw a football 60 yards. His hands were so large, in fact, they were featured in “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” and were the source of his nickname, “Mitts.”

A brief career

The NFL was integrated from its inception. In 1920, Fritz Pollard became the first African American to play in the league.

For its first decade teams signed Black players, but after the 1933 season they disappeared. An unofficial ban — or “gentleman’s agreement” — during the Depression era prevented Black players from participating in pro football from 1934-46, a year before MLB integrated. Team owners denied the existence of a ban, but there’s little explanation otherwise as to why Black players suddenly vanished from NFL rosters.

During the 1946 season, after the Los Angeles Coliseum threatened to evict the Rams unless they signed a Black player, they signed Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. A few months later, Bill Willis and Marion Motley joined the Cleveland Browns. The four men reintegrated pro football permanently. Today, nearly 70% of NFL players are Black.

Thrower went undrafted and signed with the Bears for the 1953 season for $8,500. At that time the NFL had 12 teams and only 15 Black players; Thrower was the only one on the Bears roster.

Dr. Louis Moore, a historian and author of the upcoming book “The Battle of the Black Bombers: Doug Williams, Vince Evans and the Making of the Black Quarterback,” noted it was Washington who was the first Black quarterback in 1946. The Rams tried Washington as a T-formation quarterback in the preseason and the season opener, in which he went 1-for-7 passing before being switched to fullback.

“But it’s Thrower who gets remembered as the first,” Moore said, “and that’s still really important because through understanding what happened to Thrower, we can see how pro football used the stereotype of the ‘unthinking’ Black quarterback as a way to protect the position from Black men.

“From the beginning of training camp, word from the press and players was that Thrower could not handle the position and struggled with the key aspects of learning the plays and commanding the offense. In other words, he had the physical tools — everyone marveled at his arm strength — but lacked the intangibles of brainpower and leadership to replace white men at the position and lead white men.

“When it was time to show and prove, however, he came in and played well enough to lead the team on a drive that eventually led to a touchdown. Of course, that glory was reserved for the white quarterback as the coach pulled Thrower out of the game.”

Thrower wouldn’t see action in another game that season, and then his NFL career was over. He played pro football in Canada for a few years, but a shoulder injury caused him to retire at 27.

He returned to New Kensington, where he married Mary, a woman who had grown up next door during their childhood. They moved to Yonkers, N.Y., where Thrower worked as a social worker, Mary said.

Though his playing career didn’t pan out as he’d hoped, football never really left Thrower.

“He was a humble man, loved children … he helped them wherever he could,” Mary told the Tribune. “We would go on vacations and he would see the children playing ball and he would actually stop the car and show them how you should do it this way or do it that way. That’s the kind of person he was.”

Hidden history

He and Mary returned home to New Kensington in the late 1960s to raise their children. With football now in his rearview, Thrower worked as a construction worker and entrepreneur. One of his businesses was The Touchdown Lounge, a bar whose name paid tribute to his short career.

No one in his town was really aware of the history Thrower had made, though, and the people he did tell didn’t believe him.

Even his children weren’t fully aware of what their father accomplished. Thrower rarely spoke of it, and when he did, they could sense there was a bit of pain behind the memories.

“I didn’t even realize my dad was the first Black quarterback until I was in eighth grade,” Melvin said. “If you knew my dad, he was very humble, very quiet. He didn’t walk around with an ‘S’ on his chest. A lot of people around here called him a liar. I really believe that hurt my dad, and he really never spoke about his accomplishments unless you knew him.

“I remember watching the Washington Redskins (in Super Bowl XXII against the Denver Broncos). I (was) a kid and I remember sitting on the couch with my two older brothers. When Doug Williams hoisted up that Lombardi Trophy, I heard my dad softly say: ‘Finally, finally. But one day they’ll know who I am.’”

Thrower told the Tribune in 1988 he knew “it was a Jackie Robinson-type thing,” just without the recognition.

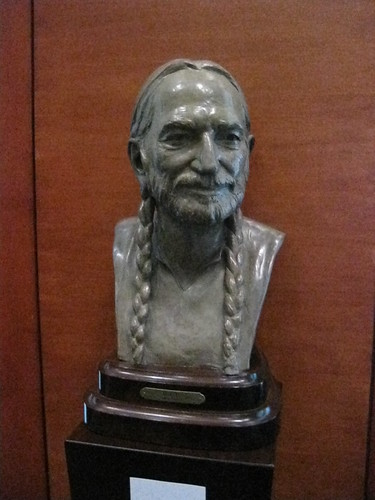

In 2006, Valley High School (formerly New Kensington High School) erected a life-size statue of Thrower. Beginning in 2021, the Willie Thrower Award has been given to the top quarterback from WPIAL and Pittsburgh City League schools. The 29-pound bronze trophy is a miniature version of the statue, made by the same artist. It’s one way the Willie Thrower Foundation has attempted to right the wrongs when no one believed Thrower’s stories.

Melvyn Smith, who isn’t related to Thrower but knew him as an uncle, serves as president of the foundation. He has dedicated much of his time to ensuring the people of southwestern Pennsylvania know who Thrower was.

“You can go through New Kensington, Arnold and Lower Burrell — three contiguous cities all with the same zip code,” Smith said. “The one thing that will remain consistent is you will never hear anybody say a negative word of Willie Thrower. Never.”

This October marks 70 years since Thrower replaced Blanda for the Bears against the 49ers. Smith and the foundation, along with the local community, plan to hold a weekend of events commemorating the occasion.

It starts on Oct. 12 with a homecoming parade, Willie Thrower Community Day, an essay contest, a basketball clinic, horseback riding and a 5k walk to benefit the American Heart Association. On Oct. 15, a local sports radio station will do a remote broadcast from the Thrower statue to conclude the four-day event.

Though the Bears have not yet agreed, Smith hopes they will participate.

“At a time when few Black players got a chance to play pro ball regardless of their position and when teams only kept two quarterbacks on their 33-man rosters, (making the Bears) shows the talent Thrower had,” Moore said. “No team was wasting a spot on a Black man if he was not good.

“I often think about how game-changing it would have been if George Halas kept Thrower and built on his talents. At the time, Halas was still one of the most respected minds in pro football and the co-innovator of the modern T-formation, the same formation that all of the pros used. For him to give Thrower his stamp of approval, and for him to show the rest of the league that you could build with a Black man and let him lead, would have been transformational.”

‘It gives them hope’

When quarterback Warren Moon was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Aug. 5, 2006, he mentioned Thrower in his induction speech.

“A lot has been said about me as being the first African American quarterback into the Pro Football Hall of Fame,” Moon said. “It’s a subject that I’m very uncomfortable about sometimes, only because I’ve always wanted to be judged as just a quarterback. But because I am the first and because significance does come with that, I accept that.

“But I also remember all the guys before me who blazed that trail to give me the inspiration and the motivation to keep going forward, like Willie Thrower, the first Black quarterback to play in an NFL game.”

Moon’s reference gave Thrower’s family validation, but Willie never got to hear his name mentioned. He died of a heart attack on Feb. 20, 2002, at 71.

His family still is waiting for him to get the celebration and recognition they feel he deserves in Chicago. Melvin said a jersey patch or something similar honoring Thrower would be “a blessing.” The Thrower family views current Bears quarterback Justin Fields as part of the legacy that Willie left behind.

“My mom would love to give Justin Fields an autographed picture of my father that not too many people have,” Melvin said. “It means so much, not to us but these other kids that (are) coming up. It gives them hope. It gives them belief that they can do it.”

The autographed photo of Thrower is rare. Melvin said Kansas City Chiefs wide receiver Skyy Moore, a New Kensington native, is the only person who possesses one.

Whether or not the Bears join them in October, the Thrower family plans to continue to honor Willie both in the way they live and in their community.

“One of my dad’s favorite sayings (was), ‘In anything you do, always be a giant,’” Melvin said.

Mary added: “He gave us that nickname and we still use it today. We are his giants.”