Visual Mandela Effect: You Don’t Know Iconic Images As Well As You Think

Mandela #Mandela

Pop quiz, hotshot: does the guy on the Monopoly box (standard edition) wear a monocle? Next question: does the Fruit of the Loom logo involve a cornucopia? And finally, does Pikachu have a black-tipped tail? If you answered yes to any of these, I am sad to say that you are wrong, wrong, wrong.

So, what’s the deal? These are all examples of the visual version of the Mandela effect (VME), which is named after the common misconception/mass false memory that anti-Apartheid activist Nelson Mandela died decades ago in prison, despite leading South Africa in the latter half of the ’90s and living until 2013. Many people even claim having seen TV coverage of his funeral, or say they learned about his death in school during Black History Month. The whole thing has VICE wondering whether CERN is causing these mass delusions somehow with the LHC.

The more attention VME gets, the more important it seems to be to study it and try to come to some conclusion. To that end, University of Chicago researchers Deepasri Prasad and Wilma A. Bainbridge submitted an interesting and quite readable study earlier this year purporting that the VME is ‘evidence for shared and specific false memories across people’. In the study, they conducted four experiments using crowd-sourced task completion services.

Experiment One: Characterizing VME

First, the team generated sets of images using forty different image concepts (e.g. Pikachu-the-idea and not surprised_pikachu.jpg or some other specific image). Of these forty, six of them had already been casually reported to elicit VME — including C3PO, the Fruit of the Loom logo, Curious George, the Monopoly Man, Pikachu, and the Volkswagen logo. The rest were image concepts like the Bluetooth icon, Hello Kitty, and Bugs Bunny.

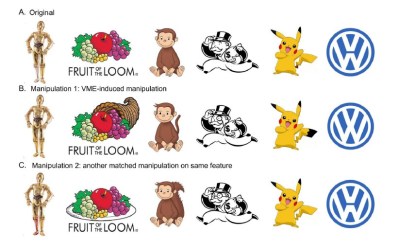

Then they made an image set comprised of three images of each concept — one unaltered, and two manipulated in GIMP. For the six VME-inducing image concepts, one of the altered images represented the reported VME version.

Then they made an image set comprised of three images of each concept — one unaltered, and two manipulated in GIMP. For the six VME-inducing image concepts, one of the altered images represented the reported VME version.

The participants were instructed to choose the canonical image from the set. In addition, they were asked to rate their familiarity with the image concept, and estimate the number of times they’d encountered it in their lifetime.

The team determined that for an image to exhibit VME, it must have five characteristics:

Their results suggest that people are just as likely to commonly mis-remember the same images as they are to correctly remember the same images. What’s interesting about Experiment One is that they picked up a seventh image concept that people commonly misremember: Waldo of Where’s Waldo? fame carries a simple brown cane, which people frequently forget about when asked to draw Waldo from memory. The team labeled these seven images as ‘VME-apparent’.

Experiment Two: Understanding the ‘V’ in VME

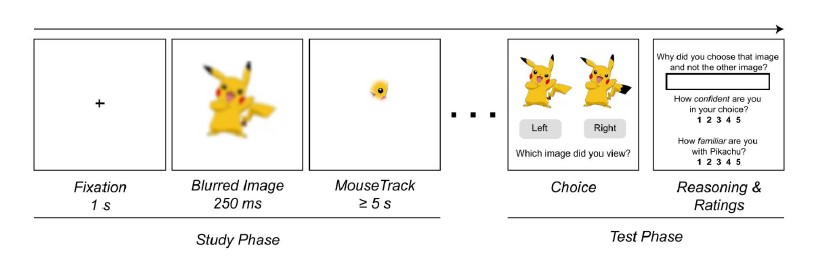

Here, the team tried to understand why the VME-Apparent Seven do what they do — induce a memory that is specific, shared, and false. They tested the study participants’ attention and perception using a program called MouseView, which is analogous to eye tracking.

The participants viewed the canonical versions of the VME-Apparent Seven one at a time on a computer screen. Each 500×500 image was obscured with a white overlay, except for a small aperture (5% of the viewing window) that moved with the mouse — move the cursor around, and you see a little bit at a time.

The participants viewed the canonical versions of the VME-Apparent Seven one at a time on a computer screen. Each 500×500 image was obscured with a white overlay, except for a small aperture (5% of the viewing window) that moved with the mouse — move the cursor around, and you see a little bit at a time.

Before seeing each image with the overlay, the participant was shown a blurred version of the whole image for 250ms in an attempt to imitate the way people take in the gist of an image at first, and use points of visual interest to guide further inspection. Then the team created a map of the points where participants fixated.

In the testing phase, the participants were shown the canonical image and the VME version and asked to choose between them. Surprisingly, many people chose the VME version to indicate what they’d seen during the trial.

Experiment Three: Quantifying VME

In the previous experiment, the team found no link between inspecting behavior while the canonical images were overlaid with white and false memories. But they believe it’s “possible that these false memories were caused by differences in the accumulated viewing experience of the cultural icons over time.” They don’t show C3PO’s legs that often in the films, so it seems reasonable that a large group of people would mis-remember both legs as being gold.

Another explanation of course is that they’ve been exposed to the VME version of C3PO given the nature of Internet phenomenons and the fact that the Mandela Effect has been covered in the media.

Another explanation of course is that they’ve been exposed to the VME version of C3PO given the nature of Internet phenomenons and the fact that the Mandela Effect has been covered in the media.

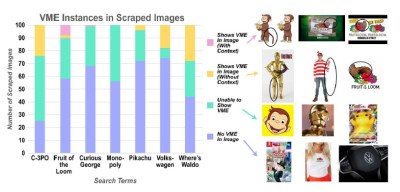

In order to quantify the weight that VME versions have on the public, the team auto-scraped the top 100 images for each of the VME-apparent concepts from Google.

They separated them into three groups — those that don’t show the VME because it isn’t there (e.g. a head shot of C3PO), those that show the whole but have no VME element (a full-body shot of ‘3PO showing the silver leg), and those that show the whole and do contain VME manipulation.

The results of people’s natural experiences varied widely among the seven image concepts. For one thing, most of the images of C3PO (51%) don’t show his legs, or do show the VME (24% have two gold legs). The number of Waldo and Volkswagen images showing VME where substantial, but not as high. Most of the rest do include the full figure, but lack elements of VME. Here, the team concluded that VME can occur even though a person has extensive experience with the canonical image.

Experiment Four: Testing for VME

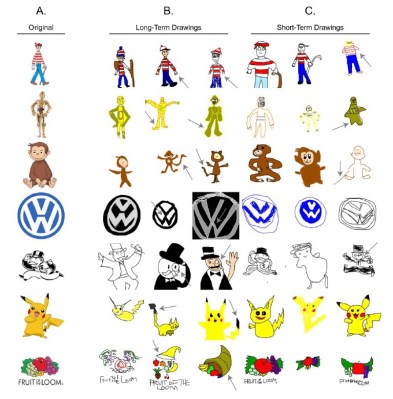

Lastly, the team tested the power of VME across memory paradigms as encountered in the first three experiments. The first two tests were visual, but the team proposes that a stronger test would be to see whether people produce VMEs without prompting. So this time, they had participants complete a web-based drawing task to see if VME occurs during free recall.

Lastly, the team tested the power of VME across memory paradigms as encountered in the first three experiments. The first two tests were visual, but the team proposes that a stronger test would be to see whether people produce VMEs without prompting. So this time, they had participants complete a web-based drawing task to see if VME occurs during free recall.

First, the participants rated their familiarity with an image concept on a scale from 1-5. People with scores less than 3 where shown the correct image for three seconds. After a one-second delay where a white screen with a fixation cross was shown, they were to draw the image from memory, spending as much time as they wanted, but with a minimum of two minutes.

People whose familiarity was ≥ 3 were asked to prove it by drawing the image from memory under the same time frame, but without seeing the image for reference at any point.

In long-term recall, C3PO, Waldo, Curious George, and Volkswagen had the highest instance of VME error in the drawings. If I may interject and defend the participants a bit — most monkeys do have tails, which suggests that Curious George is either an ape or a Barbary macaque. Since drawings from both short-term and long-term recall exercises include spontaneous VME errors, the results suggest that VME is not only an error of recognition, it can also be conjured during recall.

So What Does It All Mean?

We already knew that human memory is often unreliable, but this is usually held up in the context of eyewitness reports of events that people saw occur only one time. To study the impact of false memory among so-called image concepts that we all feel so intimately familiar with is certainly important, and quite interesting to boot. We wait with bated breath to see how the Mandela effect mutates over time, both in the standard sense and the visual.

Speaking of the visual: could you draw the Jolly Wrencher from memory? We mean accurately, of course. Try it, and let us know how you fared in the comments.