Two football players and activists died this week. Here’s the story of one: Rice’s Rodrigo Barnes

Rodrigo #Rodrigo

Whether heroes of sport deserve the level of adulation they receive has long been debated.

Still, excellence on the field has its rewards.

Making a difference off the field, away from the games, isn’t typically celebrated as loudly, but the work is more important.

Two noted athletes who stood up when it was dangerous to do so, passed away this week.

You almost certainly have heard of one of them, the great NFL running back Jim Brown. You probably have not heard of the other.

Let me tell you about Rodrigo Barnes, one of the first Black students and athletes at Rice University. Barnes died Tuesday at the age of 73.

In 1968, Barnes, Stahle Vincent, and Mike Tyler, became the first three scholarship football players at Rice. They along with basketball player Leroy Marion formed what is known as the “First Four” at Rice.

They opened the door.

Barnes, who grew up in segregated Waco, had limited interaction with whites before he arrived on campus at Rice in 1968, a place he said was like another planet at first. A planet where not all were welcoming.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

1of8

1of8

Rodrigo Barnes is flanked by Rice athletic director Joe Karlgaard (left) and President Reginald DesRoches (right) at the Ion in September 2022.

Paul R DavisShow MoreShow Less  2of8

2of8

Rodrigo Barnes, Rice University linebacker, besides being named The Associated Press Southwest Conference Defensive Player of he Week, had his name go up on the Owl’s Bluebeast Award in the locker room in Houston, Texas, Sept. 14, 1971.

Ed Kolenovsky/APShow MoreShow Less  3of8

3of8

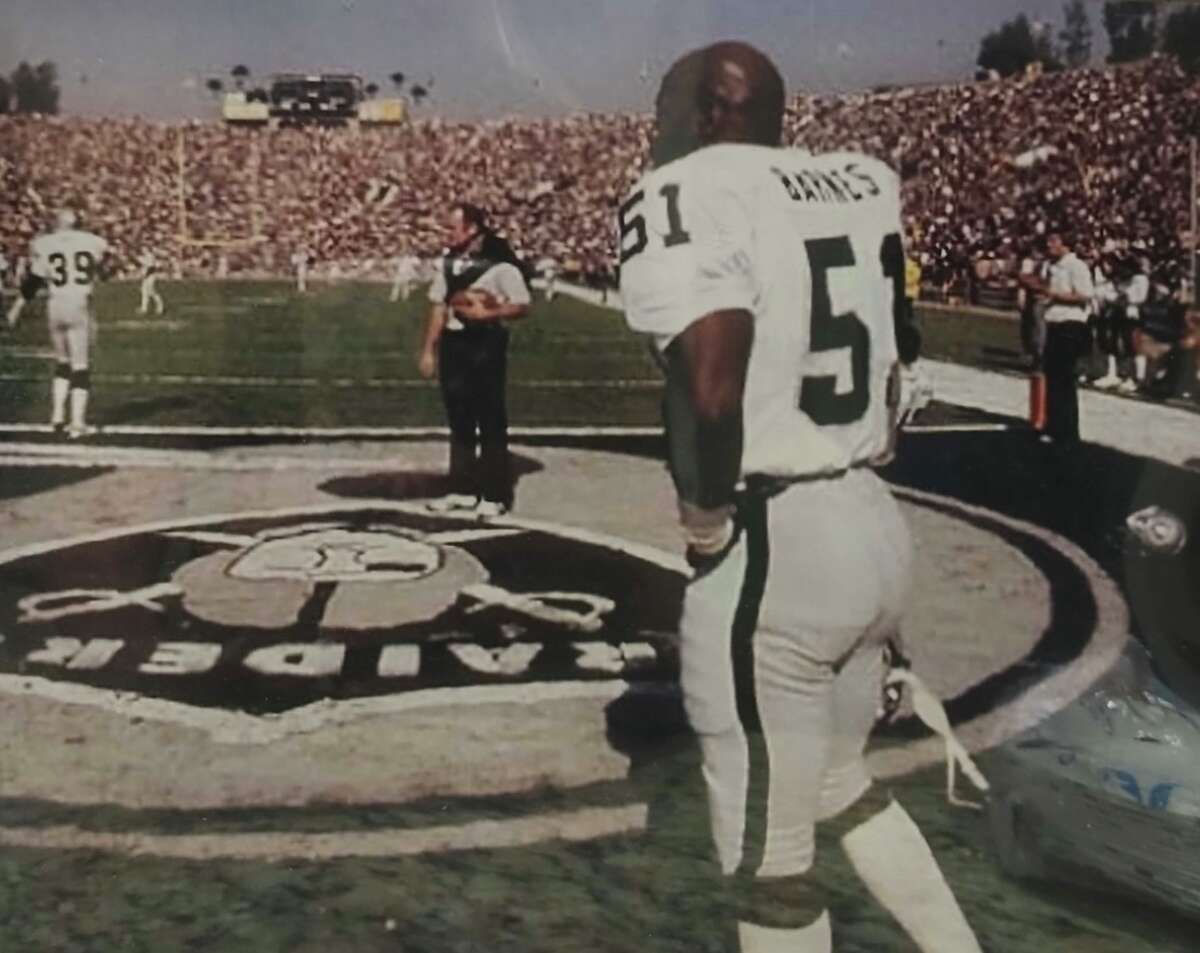

Oakland Raiders linebacker Rodrigo Barnes before Super Bowl XI against the Minnesota Vikings on Jan. 9, 1977 at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California.

Courtesy photo/Rodrigo Barnes familyShow MoreShow Less  4of8

4of8

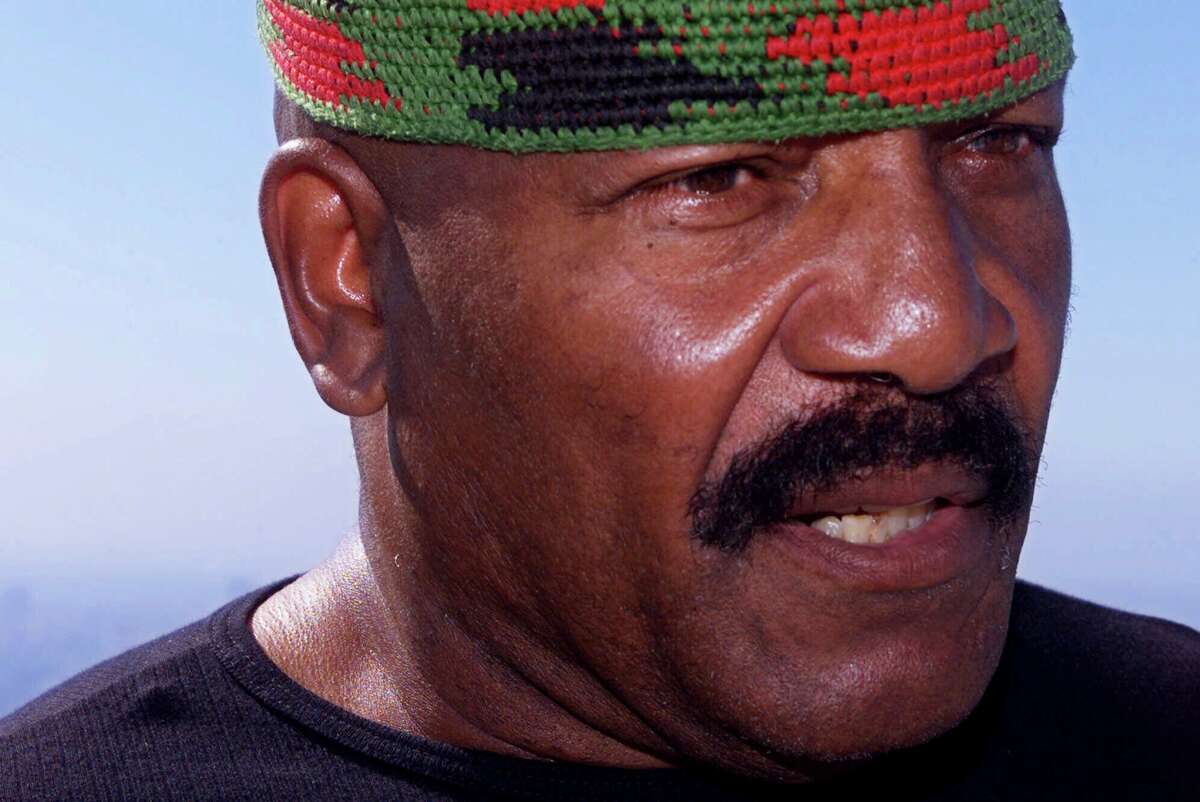

NFL legend, actor and social activist Jim Brown passed away peacefully in his Los Angeles home on Thursday night, May 18, 2023, with his wife, Monique, by his side, according to a spokeswoman for Brown’s family. He was 87.

DAMIAN DOVARGANES/Associated PressShow MoreShow Less  5of8Jim Brown runs for a gain against Washington in Washington, D.C., on July 15, 1966. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by Charles Del VecchioCharles Del Vecchio/The Washington PostShow MoreShow Less

5of8Jim Brown runs for a gain against Washington in Washington, D.C., on July 15, 1966. MUST CREDIT: Washington Post photo by Charles Del VecchioCharles Del Vecchio/The Washington PostShow MoreShow Less  6of8

6of8

Heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali, right, visits Cleveland Browns running back and actor Jim Brown on the film set of “The Dirty Dozen” at Morkyate, Bedfordshire, England. NFL legend, actor and social activist Jim Brown passed away peacefully in his Los Angeles home on Thursday night, May 18, 2023, with his wife, Monique, by his side, according to a spokeswoman for Brown’s family. He was 87.

Associated PressShow MoreShow Less  7of8

7of8

Cleveland Browns running back Jim Brown (32) with the football in a game against the New York Giants at Yankee Stadium, in New York, Dec. 18, 1960. In the fraternity of NFL standouts, Brown was revered for his dominance on the field and for his willingness to walk away on his own terms.

ERNEST SISTO/NYTShow MoreShow Less  8of8

8of8

Jim Brown, who set the National Football League rushing record of 12,312 yards while playing for the Cleveland Browns, sits pensively in his home, Tuesday, Sept. 19, 1984, Los Angeles, Calif. NFL legend, actor and social activist Jim Brown passed away peacefully in his Los Angeles home on Thursday night, May 18, 2023, with his wife, Monique, by his side, according to a spokeswoman for Brown’s family. He was 87. (AP Photo/Lennox McLendon, File)

Lennox McLendon/Associated PressShow MoreShow Less

After starring in football and track at all-Black Waco Carver High School, Barnes signed with Rice the day before Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed in Memphis.

He arrived in Houston to find that he was one of only 12 Black students at Rice.

“It was normal and natural at that time for a lot of white kids to say something derogatory to you, that’s all they knew,” Barnes said in a 2021 interview. “I’d dealt with a little of that in high school, when schools desegregated my senior year.”

Barnes said he was determined to handle whatever came his way, but knew he couldn’t get into a fight every time he heard a racial slur. Not if he wanted to stay in school.

“You’re gonna face adversity, how are you going to react?” Barnes said. “And back then, (Blacks) that were assertive, with an aggressive, leadership type personality, were usually denied.

“Racial problems were really at the main front, and I felt as though I had to prove something, so there was a little chip there. But it was about standing up and being a part of the change, a part of the development.”

A natural leader, Barnes started the Black Student Union and was the organization’s first president. The group picketed the school, calling for the university to hire Black professors and coaches for the first time.

Barnes chuckled at their audacity in being so small in number, but demanding monumental change. By the time Barnes graduated in 1973, Rice had hired its first Black professor and first Black coach.

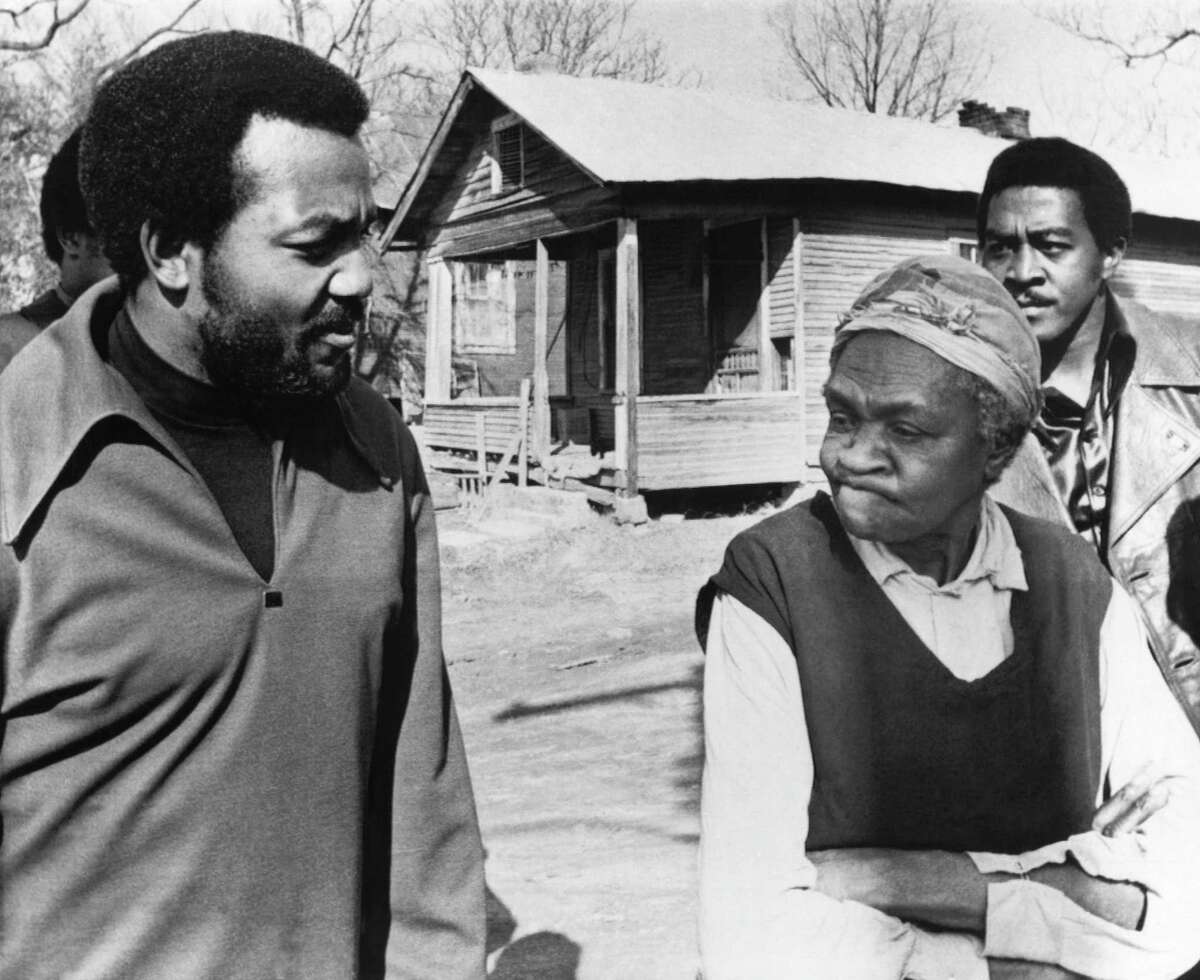

Former football great Jim Brown, left, President of the Black Economic Union, confers with Mrs. Anne Faulkner, 74, in her poor neighborhood at Holly Springs, Miss., Feb. 11, 1970. Brown led about 25 black athletes for the firsthand look at conditions his BEU hopes to improve. In background is Leroy Kelly of the Cleveland Browns. NFL legend, actor and social activist Jim Brown passed away peacefully in his Los Angeles home on Thursday night, May 18, 2023, with his wife, Monique, by his side, according to a spokeswoman for Brown’s family. He was 87.

Anonymous/Associated Press

That is one area in which Barnes and Brown had quite a bit in common. They were unapologetic in their advocacy, with an “if not now, when?” approach.

Barnes was also an outstanding player. An immediate starter at linebacker, he was a two-time Southwest Conference defensive player of the year, and the first Black defensive player named to the All-SWC squad.

After struggling early, including dealing with what he described as mistreatment by some instructors, Barnes earned a degree in sociology, behavioral science and Health & P.E. from Rice. After his NFL career ended, he returned to school at Prairie View A&M where he got a Master of Education degree.

Barnes was prouder of the work he did in education than of anything he did on the football field. He said he had more to give football, but it was beyond his control.

Barnes was certain that his draft stock fell after teams received reports from Rice that he was an activist.

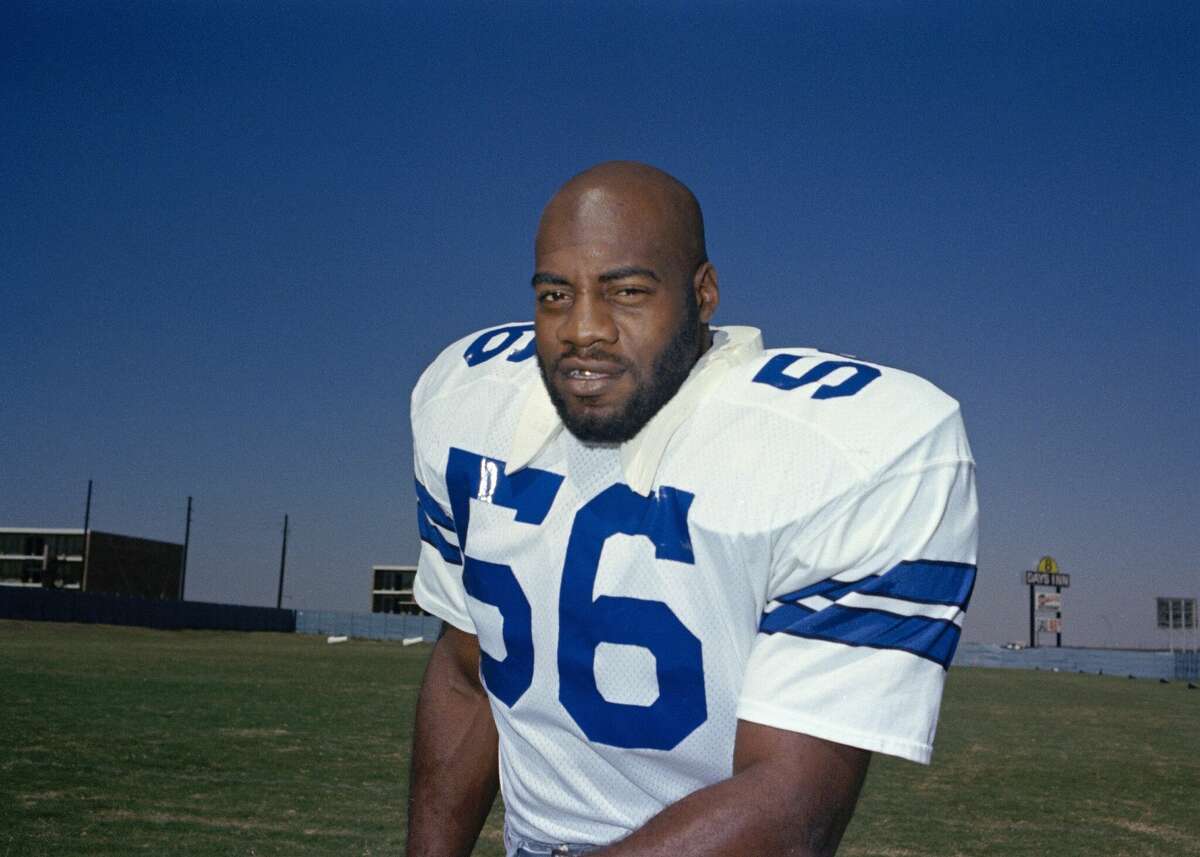

Then after being taken in the seventh round by the Cowboys (176th overall), Barnes butted heads with Dallas coach Tom Landry.

By Year 2, Barnes believed he beat out longtime middle linebacker Leroy Jordan for the starting spot, but the Cowboys weren’t willing to bench a team legend.

Barnes said he was so upset that he wouldn’t even accept the starting position at outside linebacker.

“I wanted to be the first Black middle linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys,” Barnes said. “I should have accepted my role, and been a team player, but at that time I was being selfish.”

After feuding with Landry, Barnes was benched and eventually released. He spent time with the Patriots, Dolphins, and Cardinals in an injury-plagued career.

Just when he thought his playing days were over, the Raiders called. Facing a rash of injuries, Oakland signed Barnes late in the 1976 season. Barnes saw action in the last five games and throughout the playoffs. His last NFL game was the Raiders’ 32-14 victory over Minnesota in Super Bowl XI.

“It was like God blessed me on my way out for all the hard work I’d put in before,” Barnes said.

Linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys Rodrigo Barnes is pictured, 1974.

AP

Drew Pearson, who was a rookie the same year as Barnes, said in the book “Landry’s Boys: An Oral History of a Team and an Era,” that his friend was mistreated by the Cowboys in large part due to his protest history.

“He was just a radical at a time when radicals weren’t popular,” Pearson said.

Barnes released a book in 2021, “The Bouncing Football: Life Lessons on the Gridiron,” in which he took ownership of his mistakes, because learning from them led to many successes, he said.

“I was a bouncing football, didn’t have any leadership or had some and didn’t listen to it,” Barnes said. “But I grew. We all grew. And Rice University, which I love, grew as well.

“I’m just happy I was part of the process.”