This small-town team became the Stanley Cup’s most obscure champion

Ron MacLean #RonMacLean

Eric Zweig, the hockey author and historian, was 10 years old the Christmas that his parents gave him a miniature replica of the Stanley Cup. The words inscribed on the trophy are tiny, but he was able to read them as a kid.

“That was the first time I’d ever heard of the Kenora Thistles,” Zweig said.

The gift stoked a lifelong fascination with the subject of Zweig’s latest book. “Engraved in History: The Story of the Stanley Cup Champion Kenora Thistles” introduces readers to an obscure champ – the speedy band of childhood friends from northern Ontario who claimed the title in 1907.

The Thistles represented a mining and lumber town of a few thousand people that was an outlier even in its era. With almost no exceptions, every Stanley Cup winner going back to 1893 hails from a current NHL city. Powerhouse lineups from Ottawa and Montreal traded Cup victories, except for when Kenora won it in enthralling matchups that redefined what hockey could look like.

“So much about hockey today, even the up-tempo style of play, can be traced to that (1907) Stanley Cup over a century ago,” Ron MacLean wrote in the foreword to “Engraved in History,” which was released nationally this week via Rat Portage Press.

MacLean added, “No story is smaller, which of course is what makes it so big.”

The Thistles leveraged the sport’s bygone quirks to their advantage. They were an amateur team whose top player, Tommy Phillips, lost the ends of three fingers in a lumbering mishap, yet he remained brilliant at stickhandling and shooting. Forward passes were banned, but rather than dump the puck and punt possession under pressure, Kenora’s defensemen preferred to hold onto it to orchestrate a rush.

The Thistles faced Manitoba competition because of Kenora’s proximity to Winnipeg, a shipping hub that sent Prairie grain eastward at the turn of the century and moved farm equipment in the other direction. Winters were frigid, so the region’s many good athletes were always on the ice. Phillips and his teammates rowed in the offseason, enhancing their endurance at a time when substitutions were rare.

“Art Ross would talk about it a lot: Tommy Phillips was the kind of guy who could be just as fresh at the end of 60 minutes as he was when the game started,” Zweig said. “Their fitness levels were better, and it was hard for people to keep up. And even if they tired out – by then, you’re tired, we’re tired, but we’ve already scored four goals.”

Art Ross (in black coat) played for Kenora in 1907 and won the Stanley Cup as Boston Bruins coach, shown here, in 1939. Bettmann / Getty Images

Art Ross (in black coat) played for Kenora in 1907 and won the Stanley Cup as Boston Bruins coach, shown here, in 1939. Bettmann / Getty Images

The Stanley Cup was awarded in challenge series back then: The holder was compelled to face league champions from elsewhere in Canada both during and at the end of the season. The Thistles got to vie for it in 1903 and 1905, falling to the dynastic Ottawa Silver Seven on both occasions.

Ottawa was a skilled, violent squad led by Frank McGee, the Alex Ovechkin of his era to Phillips’ Sidney Crosby. McGee was blind in his left eye and famed for scoring 14 goals in an earlier Cup game. He jabbed and broke Si Griffis’ nose in the second Thistles series, then tallied a hat trick and the late winner in the deciding contest.

Knowing they were fast enough to trouble top teams, the Thistles added ringers from a Manitoba rival – Ross and fellow future NHLer “Bad” Joe Hall – to try to dethrone the Montreal Wanderers in January 1907. They missed a connecting train en route to the series that wound up being rear-ended and wrecked.

Spared disaster, Phillips guaranteed victory in the series to a Winnipeg sportswriter, then netted Kenora’s four goals in a Game 1 win. One was sensational. Per a newspaper report that Zweig found, Phillips sidestepped most of the Wanderers while crossing the ice with the puck and wired a pinpoint shot from the right wing.

Game 2 was electric. Montreal erased a 6-2 deficit before Griffis, carrying the puck from end to end, forced two saves and passed to Roxy Beaudro for the tap-in that clinched the title for the Thistles.

“I’m sure they just thought: ‘Oh, we are the champions.’ Maybe they got cocky and sat on (the lead) a little bit,” Zweig said. “But it must have been tremendously exciting. I would love to have been at that game.”

Kenora’s reign as Cup victor lasted nine weeks. Ross and Hall returned to the Brandon Wheat City club, but the Thistles swept Brandon in the Manitoba playoffs in mid-March. Montreal visited the next week and outscored Kenora in a two-game rematch, prevailing on aggregate to head home with the chalice.

“(The Thistles) played four games against the Wanderers and won three of them. But that’s only enough to win a series and lose a series,” Zweig said. “If that’s a best-of-seven series, they’re up 3-1 at that point. Which never gets talked about, because it just wasn’t a possibility at that time.”

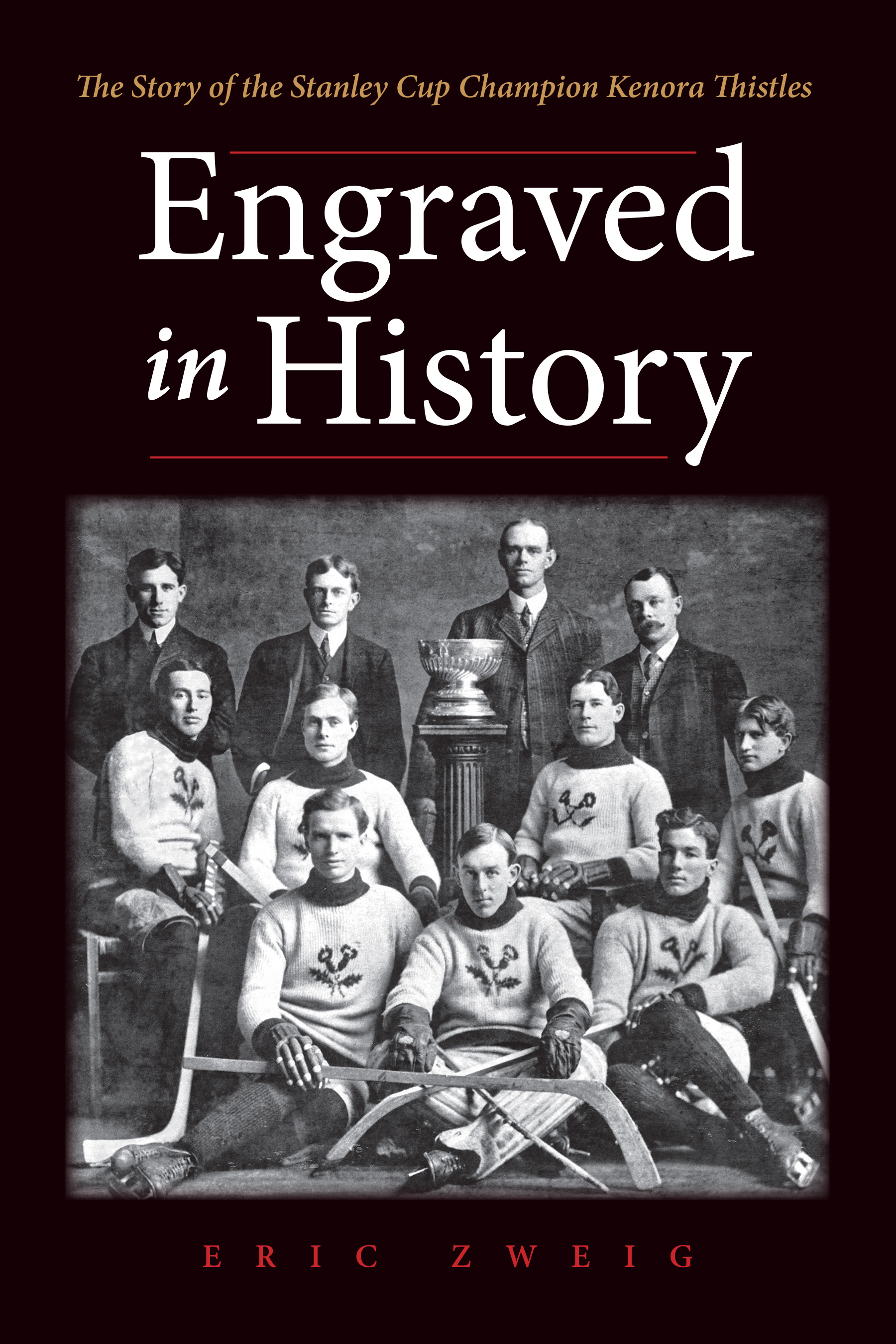

Courtesy of Rat Portage Press

Courtesy of Rat Portage Press

The dissolution of the Thistles was imminent. Most guys on the roster quit hockey or left town in the offseason, hoping to make career headway in a bigger city. A scarcely recognizable Kenora lineup lost by double digits in the 1907-08 season opener. The team folded without playing another league game.

More than a century later, Zweig compares the Thistles to the Edmonton Oilers of the 1980s. An unstoppable offense powered that franchise to several championships before it traded Wayne Gretzky for cash.

“Edmonton’s not small like Kenora’s small, but by NHL standards, it’s tiny,” Zweig said. “It’s a small, sort of underdog town playing a style of hockey that people haven’t seen before. And winning. And then going: Well, we can’t really afford to keep this team together.”

The arc of Kenora’s rise and fall raises what-ifs. Had the Thistles matured quickly enough to beat Ottawa in 1905, Zweig said, they might have held onto the Cup for three seasons. Instead, they inspired the concept of a trade deadline: Cup trustees in 1908 banned the last-minute additions of ringers like Ross and Hall.

The Thistles didn’t endure, but the prize they won did.

“The Super Bowl trophy is a cool-looking trophy, but it has no real history and they make a new one every year. The World Series trophy is a kind of dopey-looking trophy and they make a new one every year,” Zweig said. “But the Stanley Cup, even though it’s been remodeled and redone and there are different versions of it, in a sense, it’s the very same trophy that goes back to 1893 and 1907.”

“The history of this game is something we in Canada still attach ourselves to,” he added. “It’s all part of the link. And I think the fact that one small town did win is a neat part in that link.”

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.