The Mainstream Media Is Failing Trans People. These Journalists Are Fighting Back.

Trans #Trans

Society / February 22, 2024

A small but influential group of trans journalists are covering trans issues in a way that too many leading outlets refuse to do.

Ad Policy

Erin Reed.

(Marvin Joseph / The Washington Post via Getty Images)

When Erin Reed first started monitoring the spread of anti-trans legislation across the United States, she kept getting the same question from trans kids and their parents: How long is our state going to be safe for us?

In response, Reed created a map that tracks the risks that a state will pass laws targeting trans youth. But, she says, that map is no longer that useful, because just about every state seeking to ban gender-affirming care for minors has already done so. So instead, she began mapping the risk that laws targeting trans adults would pass—and 2024 is not looking good.

Predicting the future isn’t an exact science, of course. But if anyone is qualified to make an educated guess, it’s Reed. She has probably spent more time watching hearings on anti-trans bills than anyone else, and her daily newsletter has reported every detail of the fight against them for the past year and a half.

Reed’s profile—and that of other trans journalists working independently—has risen even as the mainstream media’s failures to report fairly on trans issues have become clearer than ever. Her project and others like it have filled the gap that those failures created, becoming some of the most reliable sources for information on the exploding campaign against trans rights.

This was not something Reed predicted. She says she “fell into” her current role about five-and-a-half years ago while looking for a clinic using the “informed consent” model—which allows adults to take the lead in decision-making around their gender-affirming care—so she could access hormones. The closest one she could find was over three-and-a-half hours away, in a different state; when she later discovered that several such clinics actually already existed in her area, she decided to create a map of informed consent providers in the US. It attracted attention right away, both good and bad. An anti-trans group plagiarized the map and used it to target clinics with protests and threats. But Reed says that many of the over seven million people who have viewed it since then have also used it to access healthcare.

And some of those people started keeping Reed up to date—at first with mundane information like which clinics were moving, then with bigger and scarier changes. She began sharing that information widely, first on Twitter and then on TikTok. In February of 2022, she went viral with the news that Texas Governor Greg Abbott had decided to treat people who helped minors get gender-affirming care as child abusers.

That was the moment when Reed realized that her role had changed. “People suddenly were looking at me and depending on me to know what’s going on,” she says. Unable to ignore her sense that 2023 was going to be even worse for trans people than 2022, she quit her day job with two months of savings and started publishing her newsletter full-time.

Unfortunately, Reed was right: Things in the past year have gotten a lot harder for many trans people across the US. If you’re trans and live in Florida, you now risk arrest for using many public bathrooms, and it’s illegal for your nurse practitioner to prescribe you hormones. In Tennessee and Kansas, you can no longer update the gender on your driver’s license. If you’re a trans kid, there’s a good chance that your state has made your medication illegal or banned you from playing sports.

And in every state, trans people and their families and allies have fought such legislation. Reed’s partner, the Montana lawmaker Zooey Zephyr, was one of them. When Zephyr was barred from the statehouse for saying fellow representatives supporting a gender-affirming care ban had “blood” on their hands, Reed wrote about that in her newsletter, too. Her pieces stuck to their usual tone: passionate, sure, but definitely newsy (although she was careful to disclose their relationship). On May 8, Reed wrote something different, something she called “a personal story of queer joy.” Zephyr had proposed, and Reed said yes.

In the spring of 2023, accumulating headlines continued to disregard the flood of anti-trans legislation to focus on other questions: whether all trans kids were really trans, or if the gender-affirming healthcare some of them received was really safe, or whether too many of them were getting access to such care.

Much of that coverage was showing up on the front page of The New York Times, and in April, over 1,200 contributors and 34,000 media workers and Times readers sent a letter criticizing what they saw as biased coverage at the paper of record—a letter the Times dismissed as “advocacy,” with the implication that no “advocate” could be a proper journalist.

But Reed says that her trans identity—and her deep connections within the trans community—are sources of strength for her journalism, not sources of bias. She’s able to talk to people who will not talk to any other journalists, because they know her work and they trust her. She doesn’t pretend to be neutral. Instead, she says, her work occupies a middle ground, “where my reporting itself, of the facts, is a form of advocacy.”

Most reporters couldn’t embrace the “advocacy” label, even if they wanted to. In the wake of Trump’s election in 2016, Lewis Raven Wallace, a trans journalist who worked for the public radio giant Marketplace, wrote a Medium post titled “Objectivity is dead, and I’m okay with it.” That post got him fired. But he expanded his thesis into a book, The View from Somewhere, arguing that standards of journalistic objectivity are applied unevenly. Cisgender white men are permitted to have opinions, Wallace wrote, “while the rest of us are expected to remain ‘neutral’ even when our lives or safety are under threat.”

Ad Policy

Evan Urquhart, the founder of Assigned Media—a site producing “daily coverage of anti-trans propaganda”—has published many detailed critiques of Times articles over the past year. Unlike Reed, he doesn’t identify as an activist or an advocate.

That doesn’t mean that he aims to separate his identity from his reporting. “I see myself as being in service of the trans community, and the reason that I care about serving the trans community is because I’m trans,” he says.

Urquhart launched Assigned Media in October 2022. “Like all great journalistic endeavors, [Assigned Media] was started originally out of spite,” he says. After losing out on a role as a staff writer elsewhere, he founded the site to fill what he saw as a gap in quality coverage of trans issues, even as gender was becoming an all-consuming preoccupation of the right wing.

Popular “swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Despite his habit of ripping apart biased and transphobic news coverage line by line, Urquhart got into the business because of a love of journalism—e-mailing editors at Slate until they finally let him try his hand at writing—and his work, he says, aims to hold journalism to its own professed standards. In the summer of 2023, he raised over $16,000 for a new project—the Trans Data Library—which tracks anti-trans individuals and organizations.

“The work that Evan’s doing has some really crucial tools for reporters who are just trying to understand the landscape,” says Kae Petrin, executive director at the Trans Journalists Association, a professional society of gender-expansive media workers promoting better coverage of trans communities. The TJA has created a style guide that aims to be more of a “persistent resource,” Petrin says, addressing perennial questions about reporting best practices, while the Trans Data Library gets more specific—helping reporters who would not otherwise be able to dig into the background of people pushing anti-trans legislation.

Petrin is also a data and graphics reporter at Chalkbeat, where last summer they reported a story focusing on restrictions affecting trans students in K-12 education. While they based the maps in that piece on the ACLU’s more well-known legislation tracker, Erin Reed’s more extensive and up-to-date spreadsheet was crucial to Petrin’s fact-checking and reporting process. While valuable in its own right, Petrin says, independent reporting “can support the whole ecosystem of coverage.”

But despite the available resources, people can be hesitant to report on trans issues, says Adam Rhodes, a journalist and TJA board member—either out of a fear of getting it wrong, or, more charitably, because they can’t afford to invest in the nuanced coverage they want.

But you don’t need to be an expert in trans healthcare to do this work, Rhodes says. It just takes general journalism skills: listening to sources, cutting through rhetoric, and building accurate and complex narratives. “There shouldn’t be a pantheon of five or six really good trans journalists telling trans stories,” they say. “Everybody should be doing this.”

Instead, as newsrooms everywhere continue to shrink, the people full-time reporting on the threats to trans rights—rather than debating whether trans people should even have rights—are few and far between.

That’s created an opportunity for independent journalists, Urquhart says. If you just keep doing it—“putting one foot in front of the other, every single day”—it doesn’t take much to write a big story once in a while, one that gets national attention.

When I ask him about other people doing similar work, he names plenty of names—but it can be hard to keep track, he says. People burn out, and he assumes he’s not immune. For now, he plans to keep going as long as he can.

“I wish there were 10 people doing what I do,” Reed says. Instead, she hears the same thing from people again and again: ‘I need to take a step back. This is too much, I don’t even know why I’m doing this when nothing seems to change.’”

As the anti-trans laws continue to rack up, Reed has had to reframe the way she thinks about her own work. Most of the time, she isn’t trying to change the outcome of a particular bill. Instead, she says, the goal is to document what happened, and how it happened. “Even if the bad things happen, the worst laws happen,” she says, “I’m writing for the future.”

Emmet Fraizer

Emmet Fraizer is a writer and fact-checker living in Brooklyn.

More from The Nation

America eats its young through legislation that valorizes bullying.

Dave Zirin

Republicans are working hard to destroy our public health infrastructure. Too many Democrats are helping them. It needs to stop now.

Gregg Gonsalves

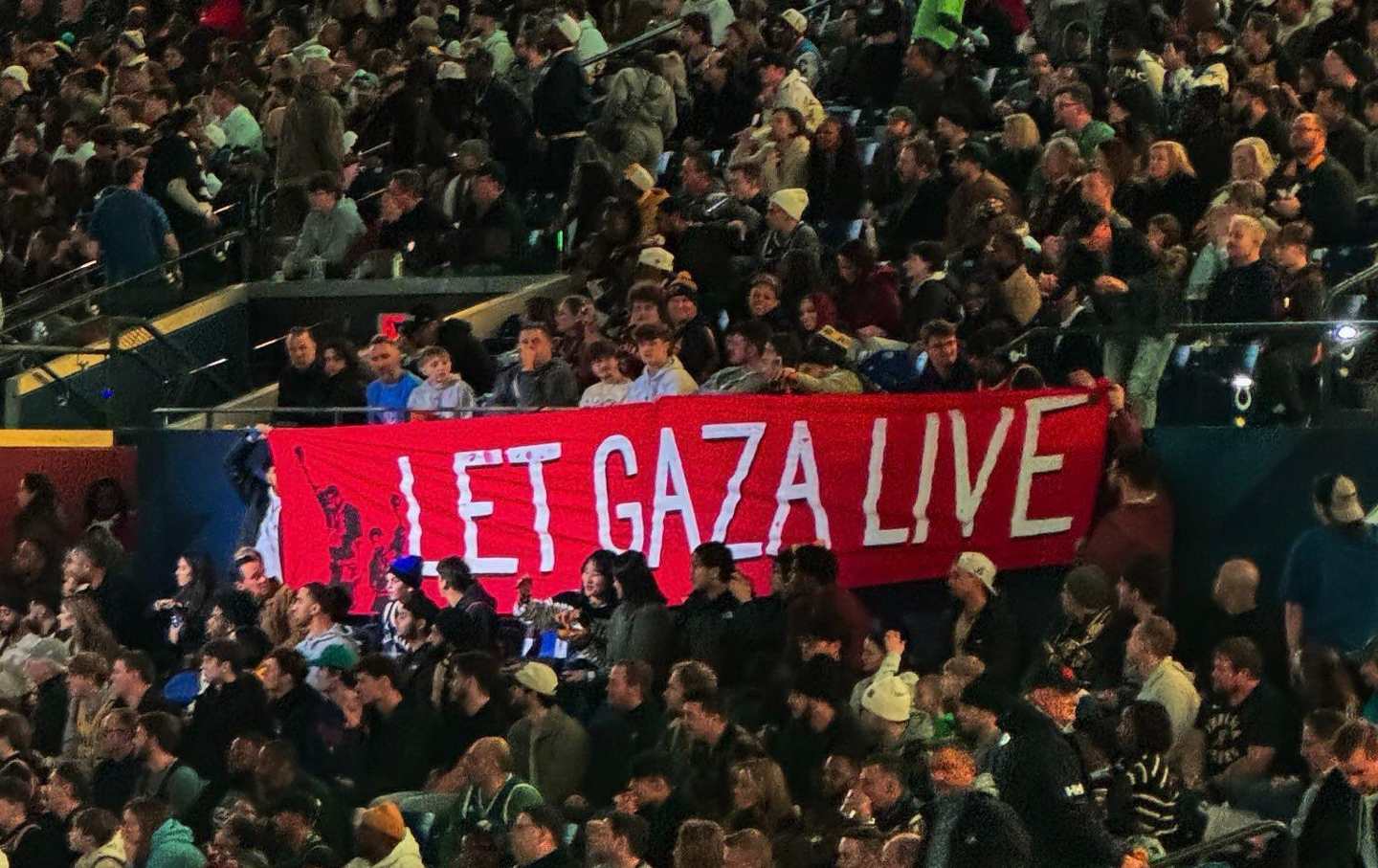

Members of the Palestinian Youth Movement and Jewish Voice for Peace unfurled a banner that read “Let Gaza Live.”

Dave Zirin

Over a dozen states reimburse services provided by these nonmedical professionals before, during, and after birth under Medicaid. But with this coverage comes new regulations.

StudentNation / Kayla Yup

There are few things more important for people in prison than keeping links with the outside world. That task falls overwhelmingly to women.

Rachel Zarrow and Christopher Blackwell

Cameras aren’t just monitoring us in public—now they’re actually yelling at us.

Column / Kate Wagner