The far-right wins big in Italy. Here’s what that means for Europe

Italy #Italy

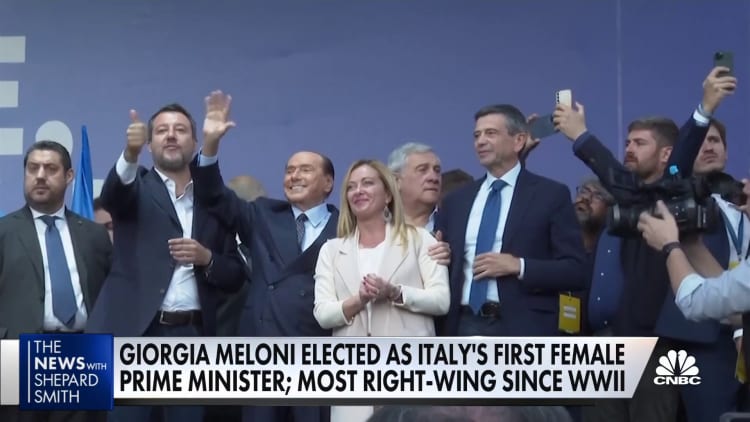

Giorgia Meloni seen speaking during the campaign. Giorgia Meloni, leader of the right nationalist and conservative party Brothers of Italy (Fratelli dItalia, FDI) held the conclusive electoral rally at Arenile, in the left-oriented district of Bagnoli, Naples.

Sopa Images | Lightrocket | Getty Images

Early results from Italy’s snap election on Sunday indicate that a right-wing coalition, led by the far-right Fratelli d’Italia party, had scooped a majority of the vote — and this could have major implications for Europe.

The alliance, made up of Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia party, as well as Matteo Salvini’s right-wing Lega party and Forza Italia, Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right party, looks set to claim victory with around 44% of the vote in both the lower and upper houses of parliament, data from the Interior Ministry showed. That compares to 26.2% won by the center-left coalition led by the Democratic Party.

As a single party, the far-right Fratelli d’Italia (or Brothers of Italy) won 26.2% of the vote, far ahead of its coalition partners Lega and Forza Italia which each gained around 8% of the vote. Turnout was low at the election, however, at 64%, compared to 74% in 2018.

watch now

Fratelli d’Italia’s runaway success means that Giorgia Meloni is likely to become Italy’s next prime minister and the country’s first female leader. The vote also ushers in the most right-wing government Rome has seen since World War II and fascist leader Benito Mussolini.

Speaking as the results emerged, Giorgia Meloni said the party would “govern for everyone” and would not “betray” the country’s trust. She also spoke of the need to unite Italy and make its people proud.

How that plays out, especially when it comes to the European Union, is now a big question for analysts, who say the coming weeks and months will determine “which Meloni” turns up to govern — the pro-NATO, pro-Ukraine Atlanticist, or the political renegade who has expressed a willingness to challenge the EU’s rules, like others on the euroskeptic right-wing.

Atmosphere during Giorgia Meloni’s rally in Cagliari to launch her campaign for Italy’s next general election at Cagliari on September 02, 2022 in Cagliari, Italy. Italians head to the polls for general elections on September 25, 2022.

Emanuele Perrone | Getty Images News | Getty Images

Politicians in that bracket certainly see Fratelli d’Italia’s success as a boost to their cause, with Europe’s right wing — from Geert Wilders in the Netherlands to Marine Le Pen in France and Viktor Orban in Hungary — hailing the party’s win on social media.

Meanwhile, there’s been a stony silence from Brussels so far, with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen yet to comment on the win for yet another right-wing faction in Europe, just two weeks after a Swedish general election saw a far-right majority get the largest share of the vote.

Still, just how far Meloni will take Italy to the right remains to be seen. Analysts note that Meloni has also cultivated a close relationship with outgoing Prime Minister Mario Draghi, who resigned in July after he failed to unite a fractious coalition around his economic policies.

“We are dealing with a right-wing coalition and we need to understand what type of right-wing coalition,” Francesco Galietti, chief executive and co-founder of political risk consultancy Policy Sonar, told CNBC Monday.

“Meloni is quite the charmer and everyone believes they have a special relationship with her, but in reality we also know that Meloni is quite close to Mario Draghi so her ascent to power is a balancing exercise. She has not ditched her old road companions but she is talking to Mario Draghi. So the question will eventually present itself: Who is the real Meloni?”

Fratelli d’Italia has experienced a meteoric rise in popularity since its founding in 2012, having chimed with sections of the Italian public concerned by immigration, the economy, jobs and living standards — ongoing challenges for Italy (and indeed Europe) that the party has pledged to tackle.

Both Fratelli d’Italia and its coalition partner Lega are nationalist parties at their core and have expressed various euroskeptic proposals in the past, even advocating for leaving the euro at one stage (although their stance on that has since softened). Fratelli d’Italia has argued for a slimmed down, less bureaucratic EU and has championed the primacy of Italian law in domestic issues.

The party has also said it would seek to renegotiate Italy’s Covid recovery funds from the EU (around 200 billion euros, or $193 billion, in loans and grants) given rampant inflation and soaring energy bills in the wake of the Ukraine war.

watch now

Ettore Greco, executive vice president of the Istituto Affari Internazionali, told CNBC that Meloni has managed to soften her past anti-EU rhetoric, but could find it hard to establish a good rapport with her counterparts in the bloc.

“For many years she campaigned on a platform that was very critical of the EU, even arguing for Italy’s exit on the euro from time to time, but now she has changed her position reflecting in a sense this strong widespread support for Italy in the EU,” he told CNBC in Rome on Monday.

“The problem she may have is that she’ll have to find a way of establishing a working, effective relationship with the EU on many difficult fields, like economic policy, because her coalition and her party have always been in favor of different rules, particularly budgetary rules and this may cause friction, especially if the economic situation worsens.”

When it comes to foreign policy, there could be some internal division within the right-wing coalition.

Fratelli d’Italia takes a pro-Kyiv, pro-sanctions position against Russia, while Lega and Forza Italia are ambivalent about punishing Moscow. Forza Italia’s Berlusconi even went so far last week as to praise Russian President Vladimir Putin and his invasion of Ukraine, saying he had done so to install “decent people” in Kyiv.

The unpredictable nature of this new right-wing coalition is bound to make EU officials nervous and Brussels has already appeared to launch a pre-emptive shot across the bow, warning Italy not to challenge it too far.

During a visit to Princeton University last week, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen was asked whether she had any concerns over the elections in Italy. She replied that if relations went in a “difficult direction” then the EU had “tools” to deal with such crises, appearing to suggest Italy could see its EU funding curbed, as it had done with Hungary, if it broke European treaties.

watch now