Terry Venables, colourful figure in English football who coached the national side to the semifinals of Euro 96 – obituary

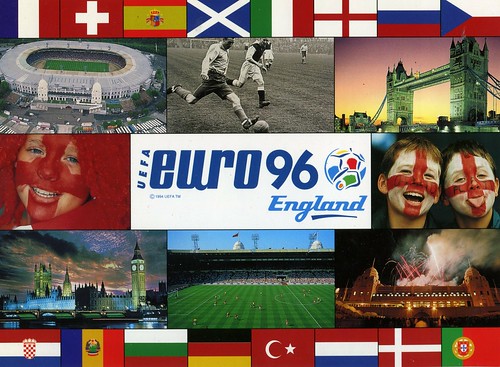

Euro 96 #Euro96

Terry Venables, who has died aged 80, competed at every level for the England football team and went on to manage the national side, leading his players to the semi-finals of Euro 96.

His character and talents radically divided opinion: to some he was an unjustly overlooked saviour of the English game, to others a footballing snake-oil salesman who promised far more than he could deliver.

Subscribers to the latter opinion could point to a trophy cabinet that hardly groaned with honours: as a player Venables won one League Cup and one FA Cup, while as a manager he led Barcelona to a single La Liga title. His critics also underscored Venables’s decidedly dodgy track record in business, a record that saw him accept 19 charges of serious misconduct in 1998 and led to a seven-year ban on being a company director.

But for fans, such run-ins with authority only served to cement Venables’s reputation as a charming East End boy-made-good, a roguish but essentially decent bloke who stuck it to the stuffed shirts at the Football Association or in the City in the finest traditions of Arthur Daley or Del Boy Trotter.

There was no denying his affability. In the early days of Venables’s career most players were largely anonymous figures – “Saturday men” who would appear before fans at the weekend, only to disappear from view again.

He wanted to carve out a much higher profile for himself, and did so often through his off-pitch activities. Aged 17, shortly after being signed by Chelsea, a well-Brylcreemed Venables took to the stage of the Hammersmith Palais to sing with the Joe Loss Orchestra.

Rapport: Venables got the best out of players including Paul Gascoigne, left – Darren Walsh/Action Images via Reuters

His determination to stand out irked some, but Venables had a crucial ability to get on with his fellow players, and later, as England manager, developed a rapport with those in the dressing room utterly lacking during the reign of his predecessor, Graham Taylor, or his successor, Glenn Hoddle.

It was not solely rapport, however, that allowed him to mould England into a team that came within an inch of reaching, and probably winning, the final of Euro 96.

Venables had already demonstrated genuine technical ability while at Barcelona, where he introduced a high-tempo pressing game at odds with the languorous style he had inherited.

With a squad full of talented midfielders and the Euro 96 tournament being staged at home, he encouraged the England side to play fluid, enlightened football, dependent on pace and width and speedy passing interchanges. As “Cool Britannia” revelled in the Britpop age, here was a new and self-confident brand of the national game to match, nowhere better displayed than in a 4-1 victory over the Netherlands.

Venables also seemed to extract the best from the notably self-destructive midfielder Paul Gascoigne. It was Gascoigne who pulled England through a turgid display against Scotland with an audacious overhead flick and volleyed goal. And against Germany in the semi-final it was Gascoigne who stretched out a leg, apparently to send his country through to the final, only to miss by an inch. Germany, inevitably, went on to win on penalties.

For Venables, who was already facing allegations of financial impropriety, which meant that his contract was not renewed by the Football Association, Euro 96 was to prove the high watermark in a career that had lasted 35 years.

Venables consoles Gareth Southgate as England’s dream of victory was ended in Euro 96 – Television Stills

Despite his troubles, however, he was still linked to almost any managerial vacancy that came up: after a brief stint with Australia, popularity alone seemed to propel him into moves to Portsmouth, Crystal Palace, Middlesbrough and Leeds. All lasted barely a year. But his enduring appeal, to players if not chairmen, was obvious.

“He’s great,” said Steve Archibald, the Scots striker who was Venables’s first signing at Barcelona. “He treats everybody like an adult, which isn’t a very common thing with football managers. He talks to you on your own level, about many things, and he makes sense. He’s confident, but not over-confident. He doesn’t brag. But I’ve never come across anyone in the game who knows more than Venables.”

Terence Frederick Venables was born on January 6 1943 in his grandparents’ house in Dagenham, east London; the house where his mother Myrtle had been staying until then was flattened by the Luftwaffe on January 7. Terry’s father Fred, a former goalkeeper for Barking Town, had been inclined to christen his son Duncan, only (so legend has it) to spot an advertisement for Terry’s Chocolates on the side of a bus and change his mind.

Young Terry grew up on housing estates in London and in Wales, where his mother had been born. In his autobiography he recalled playing football as a child in Wales with some friends when the ball smashed through a window. His London instincts propelled him to run, but when he looked back he saw his Welsh friends pooling their pocket money to help pay for the breakage. The guile of his urban upbringing was to compete with the generosity and innocence of Wales for the rest of his life.

Venables was a star of Tommy Docherty’s Chelsea – Sports press pictures

He loved playing football from an early age and established himself as one of the best players at Valence primary school, then at Lymington School – both in Dagenham. “I was already very much ‘the General’ on the field, a bit of a busybody, organising everyone,” he said. When required to identify “What I want to be when I grow up”, his response was simple: “I am going to play professional football.”

His industrious mother was dubious about this proposed course of action, and eventually the two came to an agreement: Terry could pursue a career in football if he managed to get selected for England Schoolboys. From Lymington, Venables was selected for Dagenham in 1956, then for Essex and then, finally, for England.

By the time he was 16 he was considered one of the brightest prospects in the game, a utility player in midfield who was being pursued by a host of clubs. “It seemed like half the clubs in England were chasing me,” he said. The Daily Mirror described the hunt for his signature as “the hottest since Stoke City captured Stanley Matthews”.

Though he was a Tottenham fan – aged 12 his autograph book contained the signatures of all Tottenham’s players, plus, prophetically, his own scrawl: “Terry Venables, manager of Tottenham” – Venables chose Chelsea, where he quickly broke into the first team.

There, the manager Tommy Docherty did his best to keep the youngster’s attention exclusively on football. It proved an impossible task. Venables showed a restless urge to pursue several ventures at once, backing them with enormous enthusiasm, if not similar quantities of common sense.

Only such a doomed entrepreneurial spirit could explain The Thingamywig – a hat with artificial hair mounted inside – which Venables marketed to women who wanted to go out without embarrassment when they had their curlers in.

Success with QPR – Colorsport.

Another plan saw Venables plunge into men’s tailoring. One partner was his fellow player George Graham, another the sportswriter Ken Jones. “We ended up with good suits and bad debts,” Jones noted.

There were the continued singing engagements and, in the most unlikely move of all, writing. At 18 Venables took a secretarial course to learn how to type. It was a skill that would prove useful before the end of his playing career, when he co-wrote a string of detective novels. These were eventually adapted by ITV into the television series Hazell.

Meanwhile, Venables had been made Chelsea’s captain in 1963, organising the team on the pitch in the manner he had been accustomed to doing from primary school days. This led to conflict with Docherty, and though Venables won his two international caps in 1964 (against Belgium and Holland), he was offloaded to Tottenham in 1966, having won only the League Cup (in 1965) with Chelsea.

He was not so influential at his new club, but won the FA Cup with Spurs in 1967, helping them to defeat Chelsea in the final. He then moved to Queens Park Rangers in 1969, playing 179 games and scoring 19 goals, before making his final move, to Crystal Palace.

There it became clear over the next two years that Venables’s leadership and vision could be more effectively applied from the manager’s bench than on the pitch. He was 33 when he officially made the transition, taking over from Malcolm Allison, and it was as a manager that Venables would become best known.

His first season in charge was capped by the most dramatic game of his career. Palace needed to win by two goals to win promotion to the Second Division, but were drawing 2-2 as the game moved into injury time. Two goals within 90 seconds saw them run out 4-2 winners. “It’s the most memorable game for me out of all the clubs and memories I have,” Venables said later. “It was just eerie, amazing, just like it was meant to be. It was quite amazing.”

Only two years later Venables won the Second Division title with a youthful, skilful Palace side, but after a successful start to life in the First Division, results tailed away, despite his prediction that they would be “the team of the Eighties”. In October 1980 he moved to replace his old manager, Tommy Docherty, at QPR. Venables irked some at Palace by taking many of his back-room staff with him, a practice that is now common. But he was pioneering in other, less successful, ways too.

Under his management, for example, QPR became the first club to lay down a plastic pitch (his first venture into fiction was a tale set in the future entitled “They Used to Play on Grass”). Seen as a potential owner, he was also appointed managing director of the club. He took QPR, then a Second Division side, to the FA Cup final in 1982, and the following season they were promoted to the top flight as champions. There, Venables cemented his fast-growing reputation by leading them to fifth place, and qualification for the Uefa Cup.

Venables leaves the High Court after losing to Alan Sugar in his battle over the Spurs ownership – Phil Coburn

He had become a hot property, but even so, few expected that he would be poached from QPR by Barcelona. His successful interview for the coaching role, which ended with the Barcelona president, Jose Luis Nunez, offering Venables a cigar, has become the stuff of legend. Nunez found to his embarrassment that his cigar box was empty, whereupon Venables produced a pair of Monte Cristos from his socks, where he had been keeping them for later.

He proceeded to endear himself to the fans in typically boisterous fashion, learning to sing My Way in Catalan and winning the nickname “El Tel”, which stuck long after he had left Spain.

He spent three seasons at Barcelona, winning the league title with the club at the end of his first. Having sold Diego Maradona, Venables encouraged English footballing talent to follow him to Spain, notably Gary Lineker and Mark Hughes. The side won the Copa de la Liga in 1986 and faced Steaua Bucharest in the final of the European Cup, only to lose a dire match on penalties.

His fortunes with the club began to decline the following season with a quarter-final defeat to Dundee United; he was fired in September 1987. Two months later, however, he was hired by Tottenham, the club he had supported as a boy, but where his career would ultimately founder.

1991 FA Cup Final, Tottenham Hotspur v Nottingham Forest: Venables, right, and Brian Clough lead their teams out – Sporting Pictures/Tony Marshall

He achieved moderate success there – one third-place finish and one FA Cup win – but it was his lifelong instinct to diversify and get into the boardroom that won him most headlines. The chairman, Irving Scholar, was keen to sell and battle for ownership was fought out between Robert Maxwell and Alan Sugar, whom Venables had persuaded to invest. When Sugar triumphed, he made Venables chief executive. Relations between the two were rarely cordial after that.

The battle between Venables and Sugar was fiercely waged over the next two years, with the two East End lads-made-good slugging it out for control. Though Venables’s popularity dwarfed that of Sugar (described at the time as having a charisma bypass) in the end it was Sugar who had the money, and he who prevailed.

For Venables it was a bitter exit. “People think I have a thick skin,” he said. “That’s not true. I started out very sensitive. I got hurt trusting people.” Three years later he noted: “The club’s in good shape now, but I’m on the outside, struggling.”

Barcelona manager Venables, centre, with coach Allan Harris on his right at Camp Nou watching Barcelona play Valladolid in 1986 – Colorsport/Shutterstock

It was more than a financial and personal blow, however. The fall-out led to scrutiny of his business dealings, not just at Spurs, but also at his company Edennote, and at Scribes West, the Kensington club he had bought in the early 1990s (and where he frequently took to the stage to regale punters with show tunes).

He was the subject of two BBC Panorama investigations, and the Serious Fraud Office considered a case against him over allegations of illegal loans and lying in the run-up to the Spurs takeover. The scandal cast a shadow over his tenure as England coach, and despite the success of Euro 96, it was clear he was not wanted by the FA on a long-term basis.

In the event the Department of Trade and Industry set out 19 charges against him, which Venables chose not to contest in court in January 1998. A week earlier he had left Portsmouth, a club he had bought for £1; though it was in financial disarray, he claimed a performance bonus of several hundred thousand pounds.

“We recognise his great achievement in football coaching,” noted Nigel Griffiths, minister for competition and consumer affairs, “but even our national heroes cannot be allowed to fall below accepted standards of probity when they enter the business world.”

Venables – whose later career also included brief stints with Leeds United and as adviser to the England manager Steve McLaren – certainly was a national hero to many. In 2010, backed by The Sun, he starred in a patriotism-soaked cover of the Elvis Presley classic If I Can Dream to support England during the World Cup in South Africa. The record reached No 23 in the charts, but the England side – like Venables, in the eyes of the DTI – flattered to deceive, and were soon knocked out of the tournament by Germany.

In 1964 Terry Venables married Christine McCann, a dressmaker; they had two daughters, but divorced in 1984. That year he met Yvette Bazire, who went on to manage Scribes West. They were married in 1991, and from 2014 until 2019 owned and ran a hotel in the Alicante region of Spain. His wife Yvette survives him along with his daughters.

Terry Venables, born January 6 1943, died November 25 2023

Broaden your horizons with award-winning British journalism. Try The Telegraph free for 1 month, then enjoy 1 year for just $9 with our US-exclusive offer.