Scientists detect oxygen on Venus’s dayside for the first time ever

Venus #Venus

Scientists have now captured direct detections of oxygen on the daylight side of Venus. This discovery could teach researchers more about the atmosphere on Venus. Scientists previously discovered direct detections of oxygen on Venus’s nightside, and theoretical models have long shown that atomic oxygen should exist in the planet’s atmosphere.

Tech. Entertainment. Science. Your inbox.

Sign up for the most interesting tech & entertainment news out there.

By signing up, I agree to the Terms of Use and have reviewed the Privacy Notice.

Discovering direct detections of oxygen on Venus’s dayside is exciting, especially as scientists have long yearned to learn more about “Earth’s evil twin.” Where Earth is lush and verdant, Venus is a hellscape. A hot planet with choking clouds that are composed of carbon dioxide.

One good way to look at Venus is to imagine a greenhouse environment with average temperatures up to 867 Fahrenheit. That’s so hot that all the probes sent to the surface have melted within minutes, making it difficult to learn more about Venus’s surface.

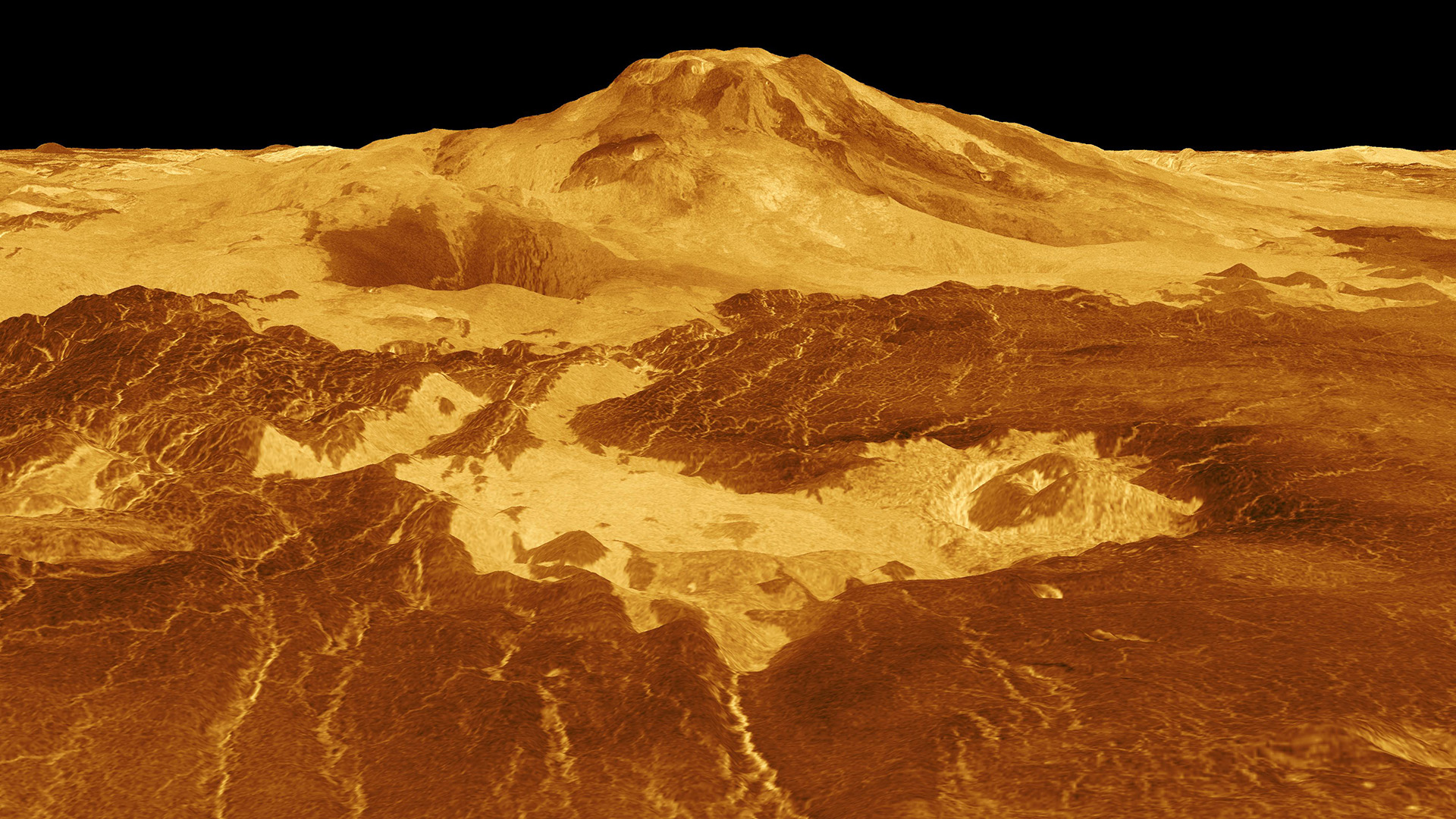

Venus is a hellscape made up of a rocky surface overlooked by a deadly atmosphere. Image source: NASA/JPL

Venus is a hellscape made up of a rocky surface overlooked by a deadly atmosphere. Image source: NASA/JPL

But atomic oxygen isn’t like the oxygen we breathe, so Venus isn’t a planet that we can breathe on or anything – even if we could survive the extreme heat. Instead, atomic oxygen is highly reactive and usually bonds to other atoms. It’s abundant at high altitudes on Earth, but it seems to be much more abundant on Venus.

Directly detecting oxygen on Venus’s dayside could teach us more about how the carbon dioxide that fills Venus’s atmosphere is created. Based on the data, scientists believe that when the carbon dioxide atoms travel to Venus’s dayside, they separate, becoming atomic oxygen and carbon monoxide. However, when it travels back to the nightside, the molecules connect again, creating carbon dioxide.

Learning more about Earth’s sister planet will help us better understand how Venus came to be the hot death pit that it is today. And it could help us better understand how climate change and other global effects may change the way that our planet looks and operates for thousands of years to come.