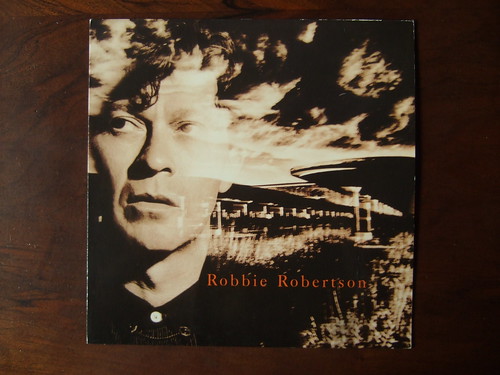

Robbie Robertson Was the Genius At the Heart of the Band’s Communal Vision

Robbie Robertson #RobbieRobertson

If there’s a moment that sums up the genius of Robbie Robertson, it’s the part in The Last Waltz when they play “It Makes No Difference.” All five brothers in the Band perform like they’re reading each other’s minds. Every detail is perfect: Robertson’s guitar, Rick Danko’s voice, Garth Hudson’s sax. They’re singing about loneliness, yet with the sound that only trusted comrades can make together. But you can hear that these guys are already mourning the death of their brotherhood. It’s their famous farewell concert, on Thanksgiving 1976. Robertson peacocks on his axe, as if he adores being on camera, but there’s no vanity at all in his guitar—only a pain as earnest as the twang in Danko’s voice.

Related

That’s why the world is grieving for Robbie Robertson, who died on Wednesday at 80. The Band was the ultimate rock & roll fantasy of friendship, with Robertson’s classic songs lighting the way. No band symbolized community like this one. You can hear that spirit in tunes like “The Weight,” as their voices trade off the line, “Put the load right on me.” They were a “band” as much as Robin Hood’s merry men, five Canadians and an Arkansan living up in Woodstock. Robbie Robertson was the mysterious songwriter at the center—the silent guitar wizard in a band of singers. Bob Dylan called him “the only mathematical guitar genius I’ve ever run into who doesn’t offend my intestinal nervousness with his rear-guard sound.”

There’s a moment in The Last Waltz where Robertson shakes his head and explains why the Band are calling it quits. “The road has taken a lot of great ones,” he tells Martin Scorsese. “Hank Williams. Buddy Holly. Otis Redding. Janis. Jimi Hendrix. Elvis. It’s a goddamn impossible way of life.” He’s talking about the road. But he might as well be talking about friendship. The Band had a unique five-way magic that sustained them, until it became the load they couldn’t carry. For them, all that togetherness really was a goddamn impossible way of life. Editor’s picks

Robertson wrote some of the most indelible songs about America, yet he was a Canadian kid, with a Mohawk mother and a Jewish father. He was just 16 when he hit the road with Southern rockabilly veteran Ronnie Hawkins. He was an outsider, but he looked around at America and fell in love. “Everything gets flatter and flatter, and wetter, and swampier, and you smell the dirt,” he told Musician in 1991. “But the most noticeable thing was the rhythm of the place. People walked in rhythm and talked this sing-song talk; when I’d go down by the river at Helena, the river seemed to be in rhythm, and I thought, ‘No wonder this music comes from here—the rhythm is already there.’ I’d hear something at night and not know whether it was an animal or a harmonica or a train, but it sounded like music to me, everything sounded like music.”

People around the world fell in love with The Band’s friendship. It was a shock for rock fans to see these guys in the photos of their 1968 debut album Music From Big Pink. They even posed with their families, with the line, “Next of Kin,” This was unheard-of in an era of generational warfare. For the cover of Rolling Stone, in 1968, they posed for Elliot M. Landy in a classic image: the five of them squeezed together on a bench, by the riverside, looking out at the snow-covered woods. They’ve got their backs to the camera, wearing their old-man suits. (People just assumed they slept in those.) They summed up that spirit in one of their Seventies album titles: Cahoots.

But as with so many bands, this brotherhood turned bitter over money. As everyone knows, Levon Helm felt burned by Robertson, and complained about him to his dying day. In a poignant 2000 Rolling Stone profile of Helm by Scott Spencer, there’s a scene on the day of Rick Danko’s funeral. Helm sits in the Chinese restaurant next door, unable to make himself go in, knowing that Robertson will be there. He just can’t do it. Levon gives up and bails on Rick’s funeral, while Robbie gives the eulogy. The article notes that there’s a ripple when he says, “I wrote the words you sang.”

“I wrote songs before I ever met Levon,” Robertson insisted in the Helm profile. “I’m sorry, I just worked harder than anybody else. Somebody has to lead the charge, somebody has to draw the map. The guys were responsible for the arrangements, but that’s what being a band is, that’s your fucking job.”

Robertson grew up playing in bands, crossing paths with a cocky Southern drummer named Levon Helm, three years older. When Levon got a gig with Ronnie Hawkins, he told his new boss about this Canadian kid who could play. So Robbie took the train to Fayetteville, Arkansas, where his new bandmates laughed at his winter clothes. Helm was his mentor, teaching him the guitar parts. As Robertson recalled, “He was my best friend, my big brother. He taught me the tricks of the trade.”

Hawkins picked up more young kids—Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson. They were a handsome crew, which wasn’t accidental. Hawkins wanted the Hawks to be hot young lookers, to attract girls to the show. It’s one of the many wonderful paradoxes of The Band that they were assembled like a boy band, to live out an American fantasy that none of them but Levon knew from the inside.

Robertson stood out as a studious-looking type, fussy and bookish. He killed the long dull stretches of the road with Faulkner and Steinbeck and Camus. Ronnie Hawkins wanted to fire him when he caught him reading. “I was reading this book The Ways of Zen and he saw it, and he just wanted to puke,” Robertson told Musician. “‘The fucking ways of motherfucking Zen. In my goddamn band. Shit, son.’ He was just disappointed.”

To their surprise, the Hawks hit the big time on the road with Bob Dylan—the scruffy garage band who turned into an international scandal, playing his new electrified rock & roll. If you’re a Dylan freak, you can spend years obsessing over every night of the Dylan/Hawks 1966 tour, from Perth to Copenhagen from Dublin to Paris. My favorite nights are Sydney and Liverpool, but the most famous gig is Manchester, where a fan yells “Judas!” Robertson replies with his awesomely monstrous electric racket, for the climactic “Like a Rolling Stone,” obeying Dylan’s command to “Play fucking loud.”

Robertson’s guitar made a perfect foil for Dylan—his painful stings at the end of “One of Us Must Know,” or his ghost-of-electricity howls in “Seems Like a Freeze-Out,” an early draft of “Visions of Johanna.” Dylan loved to hear the boys having fun, as in “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” Bur Robertson put on the chill in the longtime bootleg fave “She’s Your Lover Now,” adding some venom of his own when Dylan sneers, “Yes, and you, you just sit around and ask for ashtrays—can’t you reach?”

Up in Woodstock, the Hawks turned into “The Band,” living communally in the house they called Big Pink. Dylan was really the first fan of the Band—the loner who picked up on their gang spirit, and thrived on it, even though he wasn’t really cut out to join it. The Basement Tapes thrives on that clubhouse spirit, a gang of friends jamming in the summer of 1967 for kicks. As Dylan told Rolling Stone at the time, “That’s really the way to do a recording—in a peaceful, relaxed setting—in somebody’s basement. With the windows open…and a dog lying on the floor.” It’s a place Dylan knew he couldn’t get to on his own.

That’s why the Band symbolized friendship for so many people. The Beatles went a bit daft in their quest to be the Band, even dressing the part for their final photo shoots. Big Pink inspired the Get Back project—as you can hear George Harrison say, when he’s teaching them “All Things Must Pass,” “The thing that I feel about the emotion of it is very, you know, Band-y.”

But Robertson’s songs always had a heart of darkness. There was nothing else in pop music like “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” a song about a 1960s war rather than an 1860s one. It’s one of the Vietnam era’s most explicit—and least comforting—anti-war songs. The Band’s main audience in 1969 was draft-age American youth; nobody was innocent enough to imagine that this was a song about a previous century. It uses Civil War battles as a detail the way Springsteen uses “they blew up the Chicken Man in Philly last night”; the bloodshed is the only way Virgil Kane has to put his story on a historical timeline. Robertson wrote it for Levon to sing, and Levon remains the only voice who’s really done it justice.

After The Last Waltz, Roberston tried movie projects and a long-delayed solo career, while the remaining members of the Band ended up regrouping and touring without him. One of the weirdest but most awesome chapters of his life: He decided to be a movie star, so in January 1977, he moved in with his soulmate Martin Scorsese. What an image: two of the all-time great American dreamers holing up in Hollywood. As one of Scorsese’s exes says in Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, “It was a shame that Marty wasn’t gay. The best relationship he ever had was probably with Robbie.” No furniture in this house—they just put blinds over the windows, and soundproofed the place, to keep the outside world at bay. They stayed awake all hours, in the dark, Hollywood vampires watching movies and devouring drugs in their personal den of sin. As Robertson said, “We had only two problems: the light and the birds.” What fan of movies or rock wouldn’t love to spend a day in that house? In its way, it’s as romantic as Big Pink. Trending

It’s a painful irony that the Band ended with so much rancor, even as the world has spent years listening to the music they made together, hearing the unmistakable warmth they shared. You can hear that friendship in the songs Robertson wrote for them. It’s there in “Bessie Smith,” often dismissed as a Seventies ringer tacked onto The Basement Tapes but a beautiful tale of how music and friendship interweaving, co-written by Robertson and Danko. It’s there in “Ophelia,” kid-friendly enough for the Muppets to sing, Or “Twilight,” a lost but wonderful 1975 single with the lament, “Twilight is the loneliest time of the day.”

The world still listens to these songs to hear echoes of that friendship, one that we fantasize about, dreaming our way into that story and that spirit and that basement. In Robbie Robertson’s songs and guitar, we hear a communal spirit that we all wish we could live up to. The painful resonance in the music is that it wasn’t easy for anyone to live up to—not even the band who made it.