Restoring Pearl Harbor’s Indigenous past in Hawaii

Pearl Harbor #PearlHarbor

Looking across Pearl Harbor, the military presence in Hawaii is evident. An active navy and air force base operate on its shores. Large ships and submarines dock in its controlled harbor. Two million people per year visit Pearl Harbor to see the USS Arizona Memorial, but few know more than its military history.

This large body of water, stretching 10 square miles with lochs touching the central and leeward sides of the island, was once pristine. Freshwater streams ran down from the Waianae and Koolau mountain ranges and drained into the harbor, creating a thriving ecosystem for sea life. Pearl Harbor is named for the pearl oysters that were once so abundant that they featured in Hawaiian songs and legends, but Puuloa is its traditional Hawaiian name.

Inside the harbor’s borders were 22 hand-built, rock-walled fishponds — more than any other location on Oahu. Some of them are so ancient that traditional stories say they were built by gods.

“It was easily one of the most productive and abundant areas in the state in terms of food resources created,” Rhiannon Terearii Chandler-Iao, executive director of Waiwai Ola (formerly Oahu Waterkeeper), tells SFGATE.

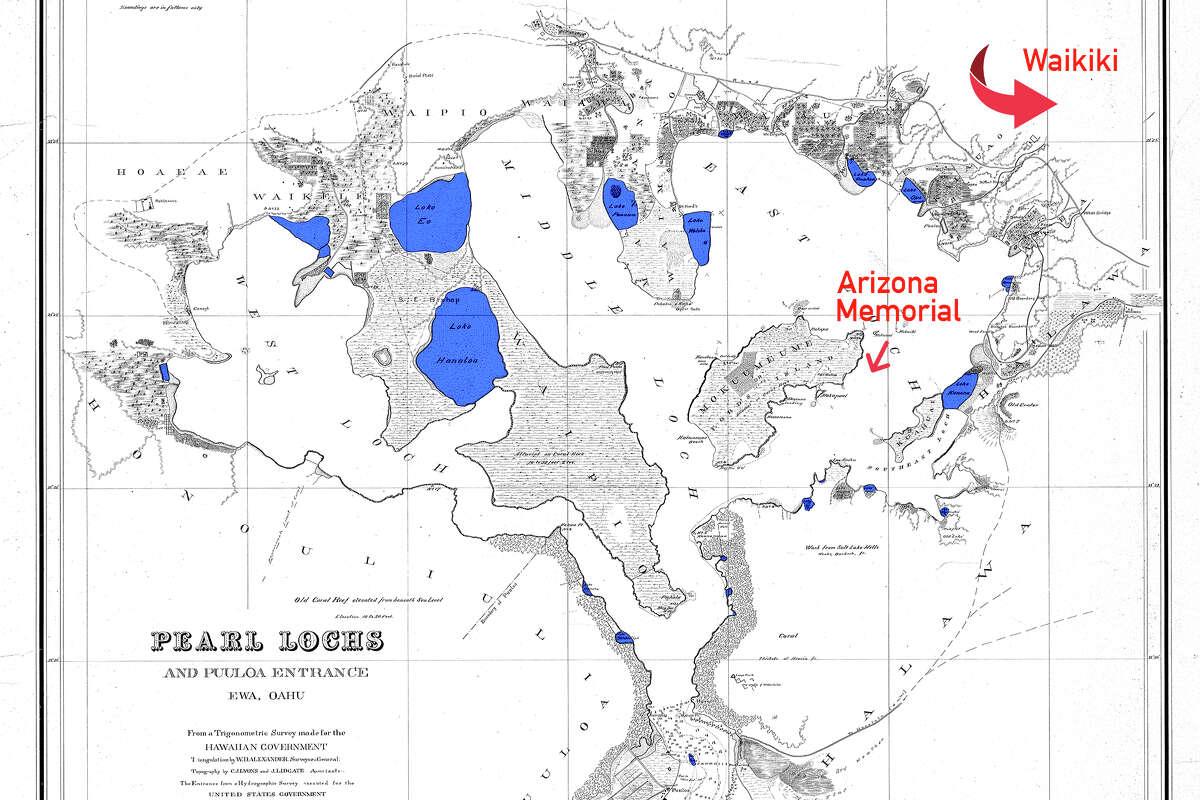

A map of Pearl Harbor in 1873 with the 22 fishponds colored in blue. Most were destroyed or filled in and, today, only three remain.

Courtesy of Hawaii.gov

Western contact disrupted Pearl Harbor’s ecosystem, and pollutants have turned a once-pristine environment into a contaminated bay.

“After contact, that area got completely exploited by the plantations,” Chandler-Iao says. “The water quality has suffered significantly over the last, I would say, 200 years.”

The sugar plantations stripped the land of forest and native plants, and streams were diverted, disrupting the harbor’s ecosystem. The Navy dredged the harbor, displacing and smothering the many creatures living there. Then there was a boom in housing development in the mid-20th century from Aiea to Waipahu and Ewa, which added to the pollutants. Most of the fishponds were destroyed or filled in and used as additional land by the military and developers.

For a long time, the native pearl oysters were thought to be lost, but Chandler-Iao and her team at Oahu Waterkeeper found four of them during a restoration project — in collaboration with the U.S. Navy and University of Hawaii at Hilo — that used other types of native oysters to improve the water quality.

Hawaii’s native oysters were used to improve the water quality of Pearl Harbor.

Courtesy of Rhiannon Tereari’i Chandler-‘Iao

“After about four years looking for the pearl oysters, and never able to identify them in the water, we finally got some to actually attach to our cages on their own,” says Chandler-Iao.

Now the pearl oysters are in the hands of UH Hilo, where they are growing and reproducing. The hope is to reintroduce them back into Pearl Harbor with greater numbers.

“Our goal in the future is to bring back the pearl oysters as well as other species of bivalves,” she says.

Of the 22 fishponds that once made up Pearl Harbor, three remain today. Paaiau, the most accessible, is a 400-year-old royal fishpond, one of three owned by a queen of Oahu before Kamehameha I conquered the island.

“My family is connected to the harbor because our great ancestor — his name was Mikalemi — and he was the last caretaker of the fishing ahu [shrine] of Puuloa,” says Kehaulani Lum of the Alii Pauahi Hawaiian Civic Club. “He did so by ensuring the Ku and Hina stones [Hawaiian deities] were honored.”

The civic club works with the U.S. Navy, which controls the land, to restore the 6-acre fishpond that was hidden away until a naval archaeologist uncovered it.

Many fishpond practitioners along Pearl Harbor died in the mid-1800s during the smallpox epidemic, says Lum. Chinese and Japanese immigrants stepped into the space and used the ponds as a fishery or rice field. Following the Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941, the perimeter was off limits. Later, land around Pearl Harbor was condemned for military and government use.

An aerial view of Paaiau fishpond, one of the more easily accessible fishponds still in existence in Pearl Harbor.

Screenshot via Vimeo | Kai Piha: Nā Loko Iʻa

“The plan calls for it to be fully restored to a working fishpond, and to serve as a cultural, educational and traditional healing space,” says Lum. Since 2014, groups of volunteers have been peeling back the layers of mangrove.

“When we remove the pilikia [problems] that has been placed in there, such as the mangrove, the garbage and the invasive species, then the native species, you see them return,” Lum says. “And so we can kind of get a sense of the abundance that was there when she was alive.”

The fishpond has given the community a space to revive the traditional cultural practice, and with continued restoration efforts, the hope is that the fish will return as before.

On the west side of the island, the nonprofit Hui o Hoohonua hopes one day that the fish in the harbor will be safe to eat. It’s one of the newest nonprofit organizations formed to clean up Pearl Harbor’s shoreline.

Its founder, Tony Chance, a retired Navy Seabee, saw the rubbish and neglect happening on the shoreline of Puuloa and wanted to do something about it.

“This is not protecting. You don’t protect people at the cost of their waters and their food,” Sandy Ward, Hui o Hoohonua co-founder and executive director, tells SFGATE.

Volunteers from Hui o Hoohonua are clearing the land for native plants.

Courtesy of Hui o Ho`ohonua

The group and volunteers clear the shoreline from trash and mangrove. It also seeks to create a public food system along the entire Pearl Harbor Historic Trail, which runs from Pearl City to Ewa. The hope, she says, would be reclaim the West Loch Golf Course, once a taro farm, and turn it into a public food system.

“That’s 80 acres of agricultural land that should be agricultural land again in the community’s hands,” says Ward. “We thought that was a crazy idea, but it’s gaining momentum.”

Volunteers from Hui o Hoohonua clear land along the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail.

Courtesy of Hui o Ho`ohonua

This would include food production, a farmers market, a place for individuals to grow their own food to create food sovereignty and food security.

“Learning from moolelo [stories], learning from other Hawaiian kiai [caretakers], it’s such an important part of our mission,” says Ward.

“That’s a really important part of addressing that historical trauma to the lands, the waters, and the people of the moku [district]. And my greatest joy will be creating pathways for young Hawaiians and young community members.”

Editor’s note: SFGATE recognizes the importance of diacritical marks in the Hawaiian language. We are unable to use them due to the limitations of our publishing platform.