Prince Andrew Helped Deepen UK Relations with Gulf Regimes for 8 Years After Epstein Scandal

Prince Andrew #PrinceAndrew

The queen’s second son held many meetings with repressive Middle East monarchies long after his role as official trade envoy ended in 2011, Phil Miller reports.

Prince Andrew in 2008. (World Economic Forum, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Phil Miller Declassified UK

In early December 2010, with the Middle East on the cusp of revolution, the Queen of England’s second son, Prince Andrew, went for a walk in New York’s Central Park. With him was Jeffrey Epstein, the U.S. billionaire and convicted paedophile, who committed suicide in prison in 2019.

When a photo of their meeting emerged in 2011, it engulfed Andrew in a scandal which forced him to give up his prestigious role as an official U.K. trade envoy by July of that year.

Yet, for much of the last decade since losing that role, he continued to represent Britain and its royal family in the highly controversial Gulf region. Andrew participated in 70 meetings with Middle Eastern monarchies notorious for repressing their own people in the wake of the Arab Spring of 2011, research by Declassified has found.

As recently as September 2019, Andrew met the new Saudi ambassador to the U.K., Prince Khalid bin Bandar, at Buckingham Palace, a year after the regime had used its diplomatic network to dismember Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

It was Andrew’s notorious interview about Epstein with BBC Newsnight in November 2019 that forced him to “step back from public duties for the foreseeable future,” putting a stop to his quasi-diplomatic meetings with Middle East monarchies, including an imminent trip to Bahrain.

While there has been media scrutiny of Andrew’s relationship with Epstein, less reported is that he retained a key role in British foreign policy long after a former U.K. official publicly raised concerns in 2010 about his “boorish” behavior in Bahrain and reputation among diplomats as “His Buffoon Highness.”

Andrew’s Arab Spring

Bahrainis expressing solidarity with the 2011 Egyptian revolution on Feb. 4. (Mahmood al-Yousif, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

In March 2011, with uprisings under way in most of the region’s eight monarchies and doubts building over his personal conduct, Andrew postponed a planned trip to Saudi Arabia to promote arms sales in his role as a trade envoy.

Buckingham Palace had to defend his suitability for the job, saying:

“Middle East potentates like meeting princes. He comes in as the son of the Queen and that opens doors. He can raise problems with a crown prince and we later discover that the difficulties have been overcome and the contract can be signed.”

The Arab Spring and the Epstein photo provoked scrutiny of Andrew from two flanks, with revelations he had entertained the son-in-law of Tunisian dictator Zine ben Ali at Buckingham Palace shortly before the North African regime fell.

Yet, Andrew was determined to maintain relations with Arab autocrats, visiting Crown Prince Salman of Bahrain at his residence in London one evening in mid-April 2011.

Bahrain’s security forces, supported by neighboring Saudi Arabia using British-made military equipment, had just crushed massive pro-democracy protests, killing more than 40 people.

Although able to meet Andrew in private, the crackdown generated so much international controversy that Salman had to decline an invitation to attend Prince William’s wedding later that month. Human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell said the invite from Buckingham Palace had displayed “shocking insensitivity to the suffering of people who have been persecuted.”

Bahraini protesters shot by military, Feb. 18, 2011. (Shaffeem, video screenshot, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

In July 2011, Andrew also succumbed to pressure and said he was standing down from his trade envoy role. Despite the announcement, little changed, with government ministers allowing him to honor “a number of pre-existing overseas diary commitments” until the end of the year.

These included a rescheduled trip to Saudi Arabia plus sessions in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Palace accounts show his flights for those trips cost the public purse £95,000, with the Foreign Office and trade ministry covering his accommodation and other expenses.

For the Saudi trip, he was accompanied by his aide, a former director of the Conservative Middle East Council, Laura Hutchings, who the Telegraph called “one of David Cameron’s most glamorous lieutenants.”

The pair landed at Dhahran military airbase, in Saudi Arabia’s eastern province where 160 members of the Shia minority had been arrested for staging Arab Spring protests. Andrew met Saudi oil executives in Al Khobar along with Saudi ministers and four princes, including Prince Al Waleed Al Talal, whom Timemagazine dubbed the “Arabian Warren Buffett” due to his enormous wealth. Al Waleed owns the Savoy Hotel in London.

By delaying the trip until after the peak of the Arab Spring protests, Andrew avoided significant controversy, although he was meeting officials from a regime which continued to suppress almost any dissent, not just domestically but also in a neighboring state.

Two months later, in November 2011, Andrew landed in Qatar for a week of meetings with other Gulf royals and business figures, accompanied by his aides Hutchings and Major-General Richard Sykes, a former British army officer.

Andrew met four Qatari royals, including the Central Bank governor, the trade minister, the prime minister and his deputy. In addition, he attended a reception given by the Anglo-Dutch energy company Shell, which owns huge gas fields in Qatar.

He then proceeded to the UAE for a visit lasting four days, giving him time to have lunch with Sheikh Suroor bin Mohammed Al Nahyan, a senior Emirati royal and owner of the Abu Dhabi trade center. On Sunday, Nov. 27, 2011, Prince Andrew met the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ), at his Bateen Palace.

That same day, a court sentenced five UAE political activists to up to three years in prison for charges that included insulting the country’s leadership. Among those convicted were the prominent blogger Ahmed Mansour and Dr. Nasser bin Ghaith, an economics professor from Sorbonne University in Paris.

Although they received a presidential pardon the day after their conviction, both men would continue to be harassed and heavily surveilled.

To round off the year, Andrew met the king of Bahrain at the luxurious Four Seasons hotel in London in mid-December. By then, the leaders of Bahrain’s pro-democracy movement had been sentenced to life imprisonment by a military court, and 559 Bahrainis were accusing the regime of torturing them.

Supporting the Saudis

Prince Andrew, The Duke of York, in a carriage procession on June 16, 2012. (Carfax2, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

After meeting four of the region’s eight monarchies during 2011, Andrew continued to play a prominent role in maintaining British relations with these regimes, even if he was no longer a formal U.K. business envoy.

In 2012, the government’s trade department praised Andrew in its annual report, explaining that,

“The Duke continues to be a strong supporter of British business and may still undertake overseas visits on behalf of this cause in the same way as other members of the Royal Family do.”

The only difference was that from April 2012, the trade department no longer held “a specific budget” to fund Andrew’s work. It said:

“In future, the associated costs of official overseas travel by The Duke will be met by the FCO [Foreign Office] in the same way as for other members of the Royal Family.”

Over the next few years, the Foreign Office would send Andrew on official tours of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, with flights costing the public at least £122,000. He also held dozens of other meetings with Middle Eastern monarchies in the U.K. and on trips abroad with his Pitch@Palace scheme for young entrepreneurs, which were supported by British diplomatic and military assets.

The afternoon session of #pitchatpalace 11.0 Boot Camp gets started with a welcome from @TheDukeOfYork – who founded Pitch@Palace in 2014.

The 42 Entrepreneurs will now Pitch their Businesses for 3 minutes in front of today’s Audience of Business, Technology & Academia. pic.twitter.com/RSEnVn5zNH

— Pitch@Palace (@pitchatpalace) May 8, 2019

Andrew flew to Jeddah in mid-June 2012 shortly after the death of Crown Prince Nayef, to present “condolences to the Saudi Royal Family” – one of the U.K. ’s closest allies in the Gulf. Nayef had served as interior minister since 1975, making him responsible for decades of crackdowns in Saudi Arabia, including the kingdom’s response to the Arab Spring protests the year before his death.

Despite the controversy surrounding Andrew’s personal life, he was greeted in Saudi Arabia by the U.K. ambassador and when he returned home the next day, Foreign Secretary William Hague went to meet him at Buckingham Palace in the afternoon.

Two years later, in November 2014, Andrew returned to Saudi Arabia at the behest of the Foreign Office, with flights costing taxpayers £43,000. By that time the human rights situation in the country had deteriorated, with the regime increasing the sentence on liberal blogger Raif Badawi from 600 to 1,000 lashes and sentencing leading Shia cleric Nimr al-Nimr to death on Oct. 15.

Protesters outside the Saudi Arabian embassy in London on Jan. 13, 2017, to mark the birthday of imprisoned blogger Raif Badawi. (Alisdare Hickson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Flickr)

During his trip, Andrew called upon the deputy crown prince, Muqrin bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, the former head of Saudi intelligence during the Arab Spring. He also visited the Saudi stock exchange with the British ambassador and retained access to U.K. diplomatic offices such as the ambassador’s residency and the consulate in Jeddah.

The month after his Saudi trip, in December 2014, Andrew’s reputation suffered a further blow when court filings in Florida showed a U.S. woman, Virginia Roberts, had alleged the Prince had sex with her when she was a minor during his friendship with Epstein.

The allegation did not go away, but Andrew continued to participate in U.K. diplomacy with Saudi Arabia. In March 2018, he joined a major Foreign Office public relations drive to welcome Saudi Arabia’s new Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), to London and portray him as a moderniser.

The Duke of York joined his mother and MBS for lunch at Buckingham Palace, followed by a private meeting with MBS at the Saudi ambassador’s residence in London.

Later that year, Andrew received the Saudi ambassador, Prince Mohammed bin Nawwaf, at Buckingham Palace on Sept. 25. A week on, Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi was killed and cut up in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, in retaliation for his criticism of MBS.

Istanbul protesters outside Consulate General of Saudi Arabia following the murder of Khashoggi. (Hilmi Hacaloglu, VOA via Wikimedia Commons)

However, Andrew said he wanted to expand his Pitch@Palace scheme into Saudi Arabia, sparking criticism from Amnesty International and others. Labour MP Lloyd Russell-Moyle told The Independent: “Prince Andrew’s open call for doing business with a man who has just ordered the murder and dismemberment of a journalist hits a new low, even for him.”

The following year, in September 2019, Andrew welcomed the new Saudi ambassador, Prince Khalid bin Bandar, to Buckingham Palace, in what appeared to be his last official meeting with a Gulf monarchy.

Boosting Bahrain

Graffiti in Bahraini village depicting eight victims of the crackdown labelled as “martyrs.” (Mohamed CJ, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

While Andrew played a notable role in maintaining ties between the House of Windsor and the House of Saud, it is in Bahrain where his presence has been most significant since the Arab Spring.

Together with his mother, he has attended the Royal Windsor Horse Show seven times since 2013, and routinely sat with Bahrain’s King Hamad.

In January 2014, he flew to Bahrain where he was received upon arrival by Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad Al Khalifa, King Hamad’s second son. Both Andrew and Sheikh Abdullah have ties to controversial celebrities. Sheikh Abdullah had a “close personal relationship” with Michael Jackson, paying millions of dollars for the singer to live in Bahrain after his acquittal on child molestation charges in the U.S. in 2005.

Andrew met Sheikh Abdullah three times during his 2014 visit to Bahrain, including at an airshow where British arms companies and aircraft were exhibiting. The event coincided with ”GREAT British week”, which marked 200 years of U.K. -Bahrain relations.

Although Andrew was no longer a U.K. trade envoy, the week was explicitly intended to boost British commercial opportunities in the Gulf and he “attended a Luncheon for the Bahrain-British Business Forum at the Radisson Diplomat Hotel”.

While in Bahrain, Andrew also met King Hamad and Crown Prince Salman, and visited the Royal Navy’s minesweeper base.

A week before Andrew’s arrival, Bahraini police had fatally shot 19-year-old driver Fadhel Abbas Muslim Marhoon. Bahrain’s police said he was shot from the front in self-defence, but evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch suggests he was shot in the back of the head.

The Duke of York returned to Bahrain in April 2018, when he inaugurated a new U.K. naval base and an academic course in “security science” for Bahraini police officers. The course is provided by Huddersfield University, of which Prince Andrew was then the chancellor.

The course is taught in Bahrain at the Royal Academy of Police’s campus, adjacent to a maximum security prison where the leaders of the country’s pro-democracy movement are serving life sentences.

According to the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), inmates have been taken from the prison to the police academy and subjected to interrogation and torture.

During his 2018 trip, Prince Andrew again met King Hamad and other leading members of the royal family including Bahrain’s interior minister, Lieutenant-General Rashid bin Abdullah Al Khalifa.

BIRD’s director, Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, has said it “sickened” him to see Prince Andrew “jovially greeting” the interior minister, given his department’s track record of systematic torture.

Andrew returned to Bahrain in March 2019 for another visit to the naval base, dinner with King Hamad and a session with Sheikh Abdullah. He then met King Hamad again in May at the Royal Windsor Horse Show.

Throughout Andrew’s engagement with Bahrain’s ruling family since the Arab Spring, the human rights situation in the country has severely worsened with most of the opposition in jail or having fled overseas.

Admiring the Emirates

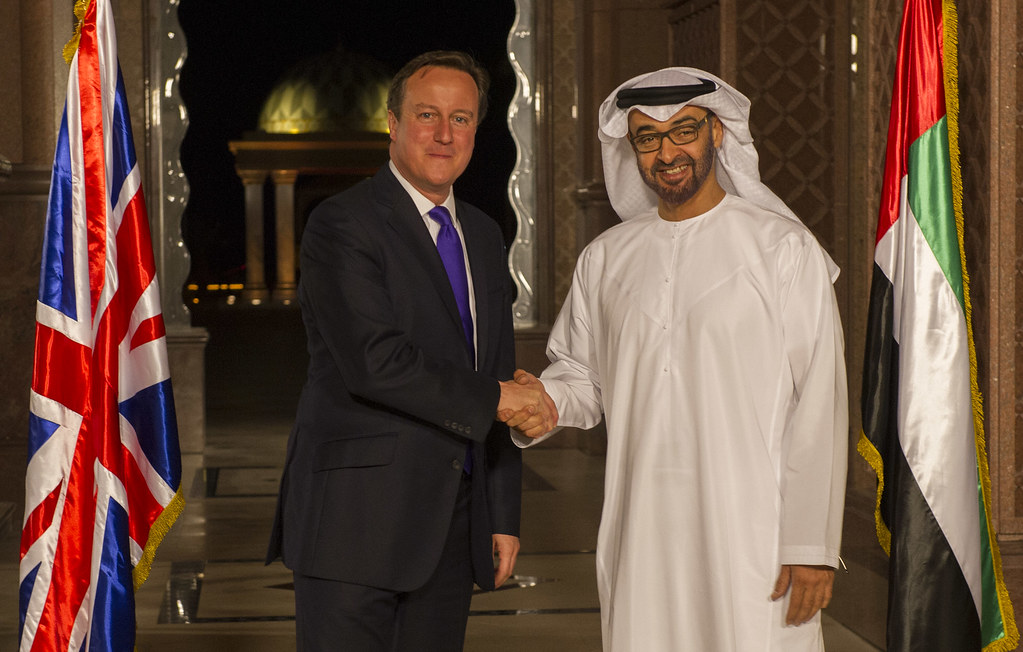

Abu Dhabi’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed or MBZ, at right, with British Prime Minister David Cameron in London, Nov. 16, 2013. (No. 10, Flickr)

Another Gulf monarchy with whom Andrew has helped deepen British relations since the Arab Spring is the UAE. Andrew is a long-term friend of Abu Dhabi’s ruler Mohammed bin Zayed (MBZ), joining him on hunting trips in Africa, according to a leaked U.S. embassy cable from 2003.

In April 2013 Andrew helped host a state visit from MBZ’s older brother, UAE President Sheikh Khalifa, an absolute ruler and graduate of Britain’s Sandhurst military academy. Andrew attended the state luncheon that was held for the Emiratis at Windsor Castle, which also featured Prime Minister David Cameron, Foreign Secretary William Hague, Defence Secretary Philip Hammond and Business Secretary Vince Cable.

Other attendees included Sir Roger Carr, who would soon become the chairman of BAE Systems, Sir John Sawers, then head of MI6, General David Richards, the Chief of the Defence Staff, and Andrew Brown, an executive director of Shell.

The next day, Prince Andrew played a more exclusive role, throwing a lunch for his parents and Sheikh Khalifa at Buckingham Palace.

Later he accompanied Sheikh Khalifa to Westminster Abbey, after the Emirati president had met Cameron in Downing Street to discuss “building a deeper and substantive defence partnership and significant new commercial links”.

The UAE state visit came at a time when Whitehall was trying to secure arms sales for British companies worth billions, during increased repression in the Emirates.

From March to July 2013, the UAE held a mass trial of 94 activists accused of ties to al-Islah, a movement associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which advocated political reform in the country. Some 69 of the men were later convicted of attempting to overthrow the government, with sentences of up to 10 years’ imprisonment.

By March 2017, Emirati authorities had stepped up their persecution of Sorbonne lecturer Dr. Nasser bin Ghaith, sentencing him to 10 years in prison for posting material online “intended to harm the reputation and stature of the state”.

This crackdown did not appear to put Andrew off his friendship with the UAE ruling family, and in October 2017 he visited MBZ at his Sea Palace in Abu Dhabi, next door to a naval headquarters.

Although his trip to Abu Dhabi was part of his Pitch@Palace scheme, he was able to attend a reception in his honor onboard a Royal Navy vessel where the British ambassador highlighted business opportunities for Emirati investors in the U.K. . Andrew was pictured onboard wearing a naval uniform, displaying his rank as a vice-admiral.

Meanwhile, the UAE’s navy had taken on a major role in the Saudi-led war in Yemen, using its relatively powerful fleet to enforce a maritime blockade which has prevented humanitarian aid from reaching millions in need.

Opportunities in Oman

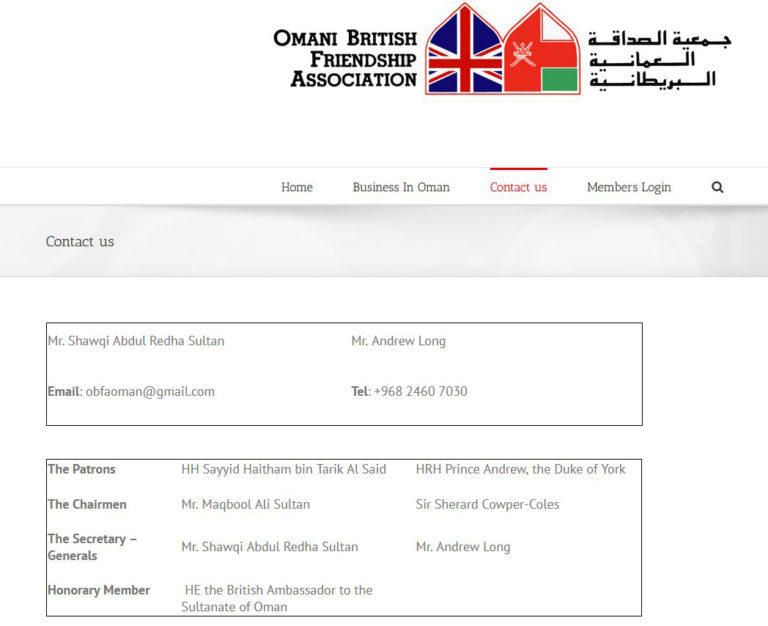

Among Andrew’s numerous honorary roles, he is a patron of the Omani British Friendship Association(OBFA), along with the current sultan of Oman, Sayyid Haitham bin Tariq Al Said. Another senior figure in the association is the U.K. ambassador to Oman, a sign of its important diplomatic and political function.

The group explicitly promotes U.K. business in Oman, highlighting its “pro-enterprise laws” and “liberal investor-friendly policies” such as zero income tax. A tweet from the British embassy in Oman in 2018 confirmed Andrew’s attendance at one event as a “guest of honour.”

.@TheDukeOfYork addressed an Omani British Friendship Association and #Oman British Business Council Reception in London on 12 July hosted by @BritOmani with HH Sayyid Haitham bin Tariq Al Said and HRH The Duke of York as Guests of Honour (via @chris_breeze) #BusinessisGREAT https://t.co/XjSBbrcCAF

— UKinOman ???? (@UKinOman) July 15, 2018

When Declassified viewed the group’s website last week, Andrew was still listed as its patron, despite giving up a slew of other roles over the Epstein scandal in 2019. The website then appeared to be taken offline after our viewing, although an archived version from December 2020 confirms his role.

The OBFA website as seen by Declassified on Feb. 18, 2021.

The group’s secretary-general, Shawqi Sultan, told Declassified that any questions about Prince Andrew’s involvement should be addressed to Buckingham Palace.

However, he did confirm that Sultan Haitham was a patron and it “had been agreed that the British Ambassador in Oman would be [a] member of the organization,” but said the “British end of OBFA was never initially an official Association”.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson told Declassified: “The Duke of York stepped back from public duties in November 2019. As such His Royal Highness currently has no active engagement with any Patronages.”

A statement by His Royal Highness The Duke of York KG. pic.twitter.com/solPHzEzzp

— The Duke of York (@TheDukeOfYork) November 20, 2019

It was partly through his role with the OBFA that Andrew met members of Oman’s ruling family annually between 2015 and 2019. The encounters often took place at Brooks’, an exclusive west London “gentleman’s club.”

Many of the meetings were with Oman’s then culture minister, Sayyid Haitham, who was secretly designated as heir to the throne and became sultan upon the death of his uncle Qaboos in 2020.

Andrew’s sessions with senior Omanis continued despite what Human Rights Watch called “a cycle of prosecutions of activists and critics on charges such as ‘insulting the Sultan’ ” of Oman, which created “a chilling effect on free speech and the expression of dissent.”

A week after Andrew’s dinner with Haitham at the Brooks’ Club in July 2016, the editor of Oman’s only independent newspaper, Azamn, was arrested and in August the paper was ordered to close.

Far from deterring Andrew, the following year he attended a dinner with Oman’s monarchy at the Royal Officer Club in Muscat.

Declassified understands that the club is a lavish leisure venue on Muscat’s seafront, complete with swimming pools, bars and sports courts, which is reserved for the upper echelons of Oman’s regime and guarded by special forces.

A Foreign Office spokesman told Declassified: “Official royal visits are undertaken by Members of the Royal Family at the request of the Government to support British interests around the globe.”

This is Part 3 of our investigation into the British Royals. Read Part 1 and Part 2 here.

Phil Miller is staff reporter at Declassified UK, an investigative journalism organization that covers the U.K.’s role in the world.

Donate securely with PayPal

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button: