On Robbie Ray, Gyro Spin, and When a Curveball Doesn’t Curve

Robbie Ray #RobbieRay

I was looking at a chart the other day, and something caught my eye. In an effort to find a good weekly article topic, I’ll usually look at a lot of pitch arsenals, and a lot of leaderboards. Here’s a fun fact. Of the 105 pitchers who have thrown at least 50 curveballs and 50 sliders on the season, there are just five of them who have run a swinging strike rate above 20% on both.

Sliders + Curves w/ 20%+ SwStr

That’s a pretty dang solid group! Sounds like an excuse for some GIFs. You’re reading PitcherList, so you might have some idea of what those pitches look like. For the most part, in a word, they’re nasty. Here’s Glasnow’s deadly combo, seen back to back.

Yikes. Yikes indeed. And if you’ve been paying attention to baseball at all over the past twelve months or so, you’ve certainly seen this pair of breakers more than a few times.

Meanwhile, Burnes’ slider doesn’t quite have the pure filth factor of those two — its movement is just a hair above average on the vertical side, and a couple of inches below average horizontally — but his curveball can definitely hang with the rest of the league.

And then there’s Robbie Ray.

That honestly might be one of the straightest sliders I’ve ever seen, and the Tropicana Field camera angle is usually not one that deceives us. Even though Ray fits in well with that crew in terms of pure swing-and-miss and strikeout ability, this is clearly a “one of these things is not like the other” situation. The eye test isn’t lying to us in those GIFs. With the exception of Márquez’s curveball, which spends two-thirds of its time in the movement-reducing high altitude, everyone on that list gets pretty hellacious movement in at least one direction on their breaking balls, making their effectiveness fairly intuitive. You probably wouldn’t need to look at the movement numbers to ascertain that Tyler Glasnow‘s secondary pitches are really hard to hit.

It’s a commonality that rings true even when you expand the list. Lowering the swinging strike threshold on the curveballs in that first list to 15% (curveballs run lower swinging strike rates than sliders anyway), the lack of movement on Ray’s pitches—especially his curveball—is impossible to not notice.

Sliders w/ 20% SwStr + Curves w/ 15%+ SwStr

Once again, we’ve got some easily identifiable nasty pitches on there. Musgrove had himself a no-hitter throwing 55% curves and sliders. In spite of his struggles this season, nobody is doubting the potency of Blake Snell‘s stuff. Sims has some of the highest spin rates in the entire league, and makes up for his lack of drop with some ridiculous glove-side cut. Jimmy Nelson is looking pretty dang good these days too.

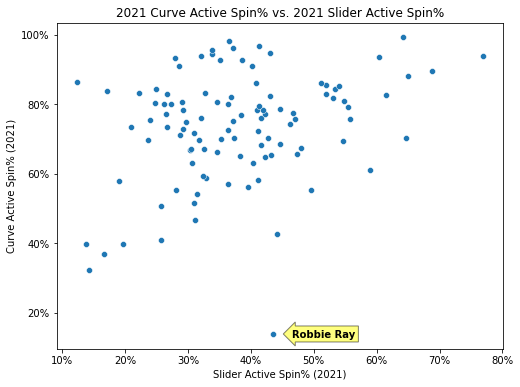

All of this is long-windedness is a lead-in to a peek at Robbie Ray‘s curveball and slider, which, as it turns out, are pretty weird! At least, relative to each other. Looking at the spin data on his Baseball Savant page, there was one aspect of his arsenal that stuck out like a sore thumb. Acting on that suspicion, I took all 105 of those pitchers who have thrown at least 50 sliders and curveballs in 2021, and had our wonderful data people plot their active spin percentages against each other. Guess which one is Robbie Ray?

Viz courtesy of Jeff Nicholas (@JeffFNicholas)

Well, spoiler. All in all, Ray’s curveball has an active spin rate of just 14%, ranking 317th out of 318 qualified pitchers, with only Jesús Luzardo checking in any lower. Before I dive a little deeper into that, let’s do quick primer on spin, active spin, and movement. All of the information that’s being shoved at us about spin and pitching can be a lot, but one concept is pretty simple. A curveball, by nature, is going to have more active spin than a slider. If you were to draw a diagonal line with a slope of one cutting that chart in half, you’ll notice that almost without exception, every dot would fall on the top half of the chart, indicating that they’re getting more active spin on their curve than their slider.

Not Ray, though! To understand why this is so weird, bear with me for a dive into the nitty-gritty of breaking ball spin and why pitches behave the way they do. First, know that the technical term for active spin is transverse spin, which is a fancy way of calling spin that’s moving in the same direction as the ball is traveling. When this happens, the ball’s spin axis — the imaginary pole around which any spinning object rotates; think of the earth and its north and south “poles” — is perpendicular to the direction it’s moving. If you’re having trouble picturing a ball’s spin axis, just think of the way the earth rotates, and how it does so at an angle.

Now, try to picture the spin axis on a spinning baseball as it’s traveling to the plate. We just change the name from transverse spin to active spin because, thanks to a physics phenomenon called the magnus effect, transverse spin is the kind that generates movement. On the other side of it, the opposite of active/transverse spin is gyro spin, of which a common illustration is a spiraling football. When a ball is spinning on an axis that points in the same direction that the ball is traveling in — again, think of how the pointed end of a football is (ideally) always aiming towards its target — the spin doesn’t create movement. For a much more in-depth (though jargon-y) explanation of how all this works, check out the work of Alan Nathan and David Kagan, actual physicists, who have written some excellent primers on the subject.

Back to the point: why does a curveball usually have more active spin than a slider? It’s pretty simple. When throwing a curveball, a pitcher is trying to put topspin on the ball, essentially the opposite of the backspin you see on a fastball. Just like you need a lot of active spin to throw a good “rising” fastball, to get a pitch to plunge down nearly 60 inches from its release point like Glasnow does, you have to get a decent amount of spin that’s actively pushing the ball downward.

With a slider, however, the pitcher is trying to do something a little different. In theory, the ideal slider will have perfect sidespin, transverse spin that goes perfectly right to left for a right-handed pitcher and left to right for a lefty, creating the sweeping, side-to-side movement typical of a classic slider. However, this is much easier in theory than in practice. If you can, go pick up a baseball and pretend to throw it. Simply put, it’s a whole lot easier to throw a ball forward with topspin than sidespin. Seriously, try it. You can’t! You’d have to start across your body and throw it like a frisbee. It’s just not really possible.

The result of that is when pitchers are trying to throw a slider, they’re never going to be able to get that perfect sidespin, just because of the way our hands and wrists work while throwing a round ball. As a result, most sliders are going to have a ton of gyro spin, because this is how things look when you try to push a baseball’s spin to the side when you throw it.

This tweet right here helps demonstrate why there are so many different kinds of sliders that move in a million different ways. If a pitch is all gyro spin, then it’s not going to move at all — like a football, remember? But there’s still a little more to it. The matter is complicated by the fact that there’s little consistency from pitcher to pitcher as far as how much gyro they have on their sliders.

Most fastballs fall into a relatively small range of active spin rates. 408 of 484 qualified pitchers have four-seamers with between 80% and 100% active spin. The amount of active/gyro spin on a slider, however, can vary wildly depending on an individual pitcher’s grip and release. For example, with more than 65% active spin, 16th-highest among qualified pitchers, Shohei Ohtani‘s slider gets an absurd 18 inches of horizontal movement.

On the other end of the spectrum, you have Luis Castillo and his slide piece, which is on the very low end of things with just 17% active spin. It gets just a single inch of horizontal movement on average, but with a solidly above-average 39 inches of vertical movement, it still gives hitters fits.

With all of that being said and shown, let’s make our way back to Robbie Ray. Again, remember that with all of the different ways that one can throw a slider, one thing is generally true across the board: a pitcher’s slider is going to have more gyro than their curveball. When throwing a curveball, a pitcher is usually trying to get as much active spin on the pitch as possible, because that what creates your classic curveball movement. Sliders are a lot more nuanced, as we saw, but the nature of the way the pitch is thrown means that it’s almost always going to have a heavier gyro element than the same pitcher’s curveball.

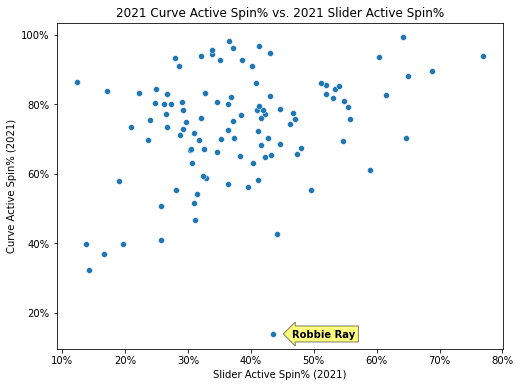

Robbie Ray seems to be a rule breaker. Here’s that chart one more time, to save you the trouble of scrolling up.

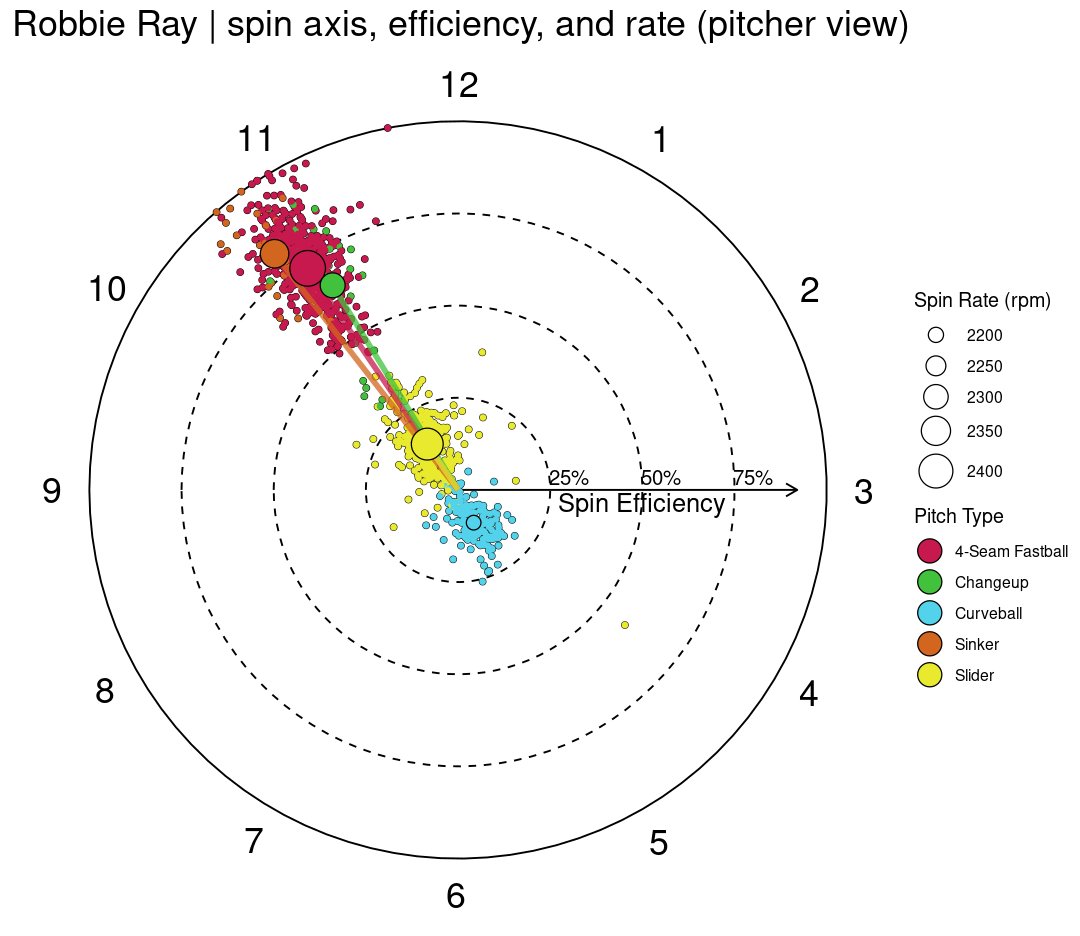

Anytime you have a point on a graph that looks like that, my first assumption is that there’s some kind of labeling error or other malfunction. That is quite the outlier. My first instinct was to think that Savant was simply getting his slider and his curve mixed up. Picking the brain of Max Bay (@choice_fielder), one of the smartest public-facing people in the baseball world working on spin, movement, and quality-of-pitch modeling, he offered that it probably doesn’t even matter what Ray calls his pitches — in terms of actual function, his slider is more of a cutter, and his curveball more of a slider. Objectively, he’s correct. Using some of Bay’s super cool pitch arsenal visualizations, we can see that handedness and fastball variation aside, the difference between Ray’s arsenal and Blake Treinen‘s arsenal last season is more about semantics than any actual difference in the way the pitches spin and move.

Further research indicates that this isn’t just a pitch classification snafu, though. It’s not some kind of recent adjustment that’s gone hand-in-hand with his year-over-year turnaround. His pitch profile is more or less unchanged since 2020.

Even though it seems like it might be significant that the pitch was reclassified from a regular curve to a knucklecurve, there’s not any public evidence that anything has actually changed. 2020 is the only season that Savant has called the pitch a regular curveball instead of a knucklecurve, and as recently as 2019, Ray was still using the same spiked grip that he developed way back in 2017. There’s just something unique about his wrist action when he releases the pick that gives it more gyro and less active spin than almost any other in the game. I’d love to see some slo-mo footage of his hand at release, but until that’s a possibility, I’ll have to settle for accepting that it’s just unique in a way that will remain mysterious.

1500 words later, we have our explanation for why Ray’s curve and slider don’t have the movement that’s typical of pitches that draw as many whiffs as they do. That doesn’t tell us why they’re still effective, though.

That’s a question that’s more or less unanswerable — Bay says that his proprietary system for measuring pitch quality (he calls it Stuff+) doesn’t think Ray’s curveball should be a good pitch either, in spite of a CSW pushing 40%. There are a lot of potential reasons, some of which may be more relevant than others. There’s the tunneling factor: that is, the fact that neither of his breaking pitches has much movement might not matter if the batter can’t tell which is which until the last second. Looked at in chart form, Ray’s pitch movement is much more clustered than is typical, with John Means demonstrating a more standard curve/slider movement split.

Tunneling and sequencing are quite fungible in terms of what causes success and failure; as my podcast co-host Ben Palmer likes to say, who’s to say what’s good or bad? Sometimes two breaking balls “bleeding” together can be a disaster and make them easier for hitters to see, and sometimes it makes it even harder for a hitter to know what’s coming. It’s impossible to say.

There’s also the dark magic known as seam-shifted wake. You can learn all you need to know about seam-shifted wake from Barton Smith’s excellent PitchCon presentation from earlier this year, but the long and short of it is that there exists another physics phenomenon that can cause a pitch to move in ways unrelated to transverse/gyro spin and spin axis. We still don’t understand much about this kind of movement, but it’s a lot less straightforward than the magnus effect-related movement that comes from spin.

We can detect seam-shifted wake in a pitch by seeing if there’s a disparity between the way the ball should be spinning based on its tracked movement, and the way the ball is actually spinning, as observed by the ultrapowerful Hawkeye cameras installed in MLB parks prior to last season. If there’s a big difference between a pitch’s calculated spin direction and its observed spin direction, it means that a pitch is moving in ways that aren’t solely attributable to spin and the magnus effect. Seam-shifted wake is most commonly detected in sinkers and changeups, because of the grips typically used on those pitches. Ray’s gyro curveball, however, appears to get more seam-shifted wake action than almost any other in the league, as measured in degrees of difference between the observed and calculated spin axes.

Largest Curveball Observed/Inferred Spin Gaps

Again, it’s impossible to say for sure if or how much this has to do with the effectiveness of the pitch(es), but it does tell us that there’s some outlier business going on here, and having an outlier pitch on either end of the spectrum can certainly be a good thing.

It also prompts some reconsideration of what makes an effective curveball. Just as with fastballs, having more active spin on a curveball is usually better than having less, because the goal is generally to get the ball to move as much as possible. Knowing there are other, less straightforward ways of making the ball move suggests that pure movement isn’t necessarily the be-all end-all for pitch nastiness. Critically, with all of the information we have dating back to last season, a sample of 300+ pitcher seasons, there’s a demonstrable relationship between gyro spin and seam-shifted wake that doesn’t exist with other breaking balls.

Viz courtesy of Jeff Nicholas (@JeffFNicholas)

If you remember the first couple paragraphs of this increasingly long-winded article, it might have caught your eye that Luzardo, the only curveball with less active spin than Ray’s, has twice as big of a spin axis deviation as almost any other, including Ray’s. Doesn’t seem like so much of a coincidence now, does it?

But again, as Ben would have it, who’s to say what’s good or bad? None of this tells me much more about Robbie Ray, but it does tell me that we can learn something from him. Many pitchers aren’t blessed with the natural high spin and feel for a high active spin rate on their curveballs. As we learn more about seam-shifted wake, we open up new possibilities for effective and “nasty” pitches beyond the scope of the Glasnow-esque breaking balls that make for good GIFs. If a pitcher is stuck with a middling curveball without any particularly compelling characteristics, why not buck conventional wisdom and start chucking that thing with more gyro spin and less raw movement? Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that the other pitcher on that very first list without exceptional movement on his breaking stuff, Márquez, ranks 307th out of those 318 qualified curveballs with just 32% active spin, although that’s still nearly 20 points higher than Ray. Who knows!

As per usual, this is almost all guesswork. Even the experts still don’t have a perfectly solid grasp on this stuff, and I am far from an expert. But I know an interesting arsenal when I see one, and whatever the root causes for the effectiveness of Ray’s breaking balls are, it’s a wonderful example of how almost everything in baseball contains quite a bit more than what meets the eye.

(Photo by Cliff Welch/Icon Sportswire)