Music Reissues Weekly: The Beatles – Get Back

The Beatles #TheBeatles

And the point of view with director Peter Jackson’s interpretation of the 60-plus hours of film and over 150 hours of audio from The Beatles’s January 1969 attempts to make a film or television special and an album is his – and those who signed-off the 468 minutes first seen via streaming and now available on Blu-ray or DVD. None of this is to say the new Get Back is redundant but that it, like any other new Beatles release, arrives with caveats centring on the degrees to which history has been re-written. Or erased.

The album which emerged a year later was Let It Be. The film of the same name was also seen in cinemas. Even though the source footage (and audio) drawn from in Jackson’s Get Back is what was captured in January 1969, it is not an upgraded version of 1970’s Let It Be film. A full viewing confirms it does not replace that, but instead complements it.

The album which emerged a year later was Let It Be. The film of the same name was also seen in cinemas. Even though the source footage (and audio) drawn from in Jackson’s Get Back is what was captured in January 1969, it is not an upgraded version of 1970’s Let It Be film. A full viewing confirms it does not replace that, but instead complements it.

What Jackson and his team have arrived at is astounding. Astounding as it brings shape to what was going on in Beatle-world in January 1969, and astounding as the quality of the visuals and audio is stunningly crisp without being inauthentic. There is a lack of gloss, yet the massive amount of technical work is evident.

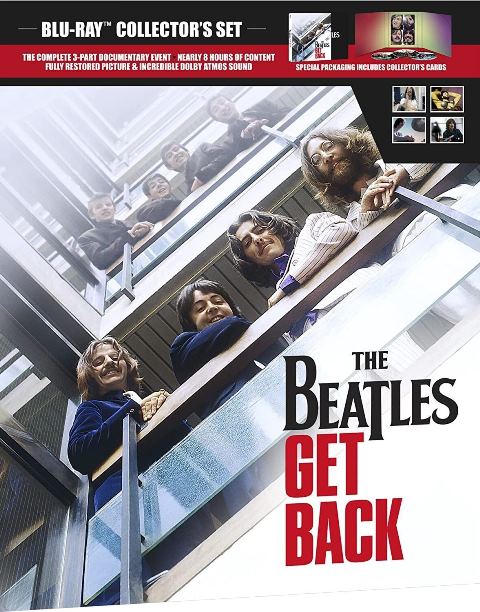

Memories of the original Let It Be film indicate that for The Beatles January 1969 was dismal, especially during their initial stint at Twickenham Film Studios. The 1970 film of what went on was murky: visually and spiritually. A miserable band either bitched with each other or was morose. OK, they thrillingly played the rooftop of their Savile Row headquarters but nothing looked as if it was fun. An initial scan of the Blu-ray package’s positive imagery suggests such recollections are to be determinedly upturned. Nonetheless, despite the smiles in the photos used it’s all here, all the bad stuff: even more so than in the 1970 Let It Be film. There’s good stuff and upbeat vibes too – a balance – but this is no snow job or whitewash.

By adopting a day-by-day approach to the footage and, when it covers the same ground as the Let It Be film, using alternate camera perspectives, the wretched is not sidestepped. Harrison leaves. Beforehand, McCartney badgers him. No one seems interested in the songs Harrison brings to proceedings. Multiple instances of McCartney lengthily and tediously questioning what it is they are doing are tiresome, even though the band needed direction after the death of manager Brian Epstein. As it’s put, a “daddy” is required. In the main, Lennon sits blank-faced during McCartney’s wearisome expositions probably as a result of his then-current heroin use. Ringo Starr rolls with it. It’s obvious what Harrison thought.

In this context, it is extraordinary that dogged original director Michael Lindsay-Hogg repeatedly pushes the band on what this aiming at; what sort of concert are they going to do, where and how? Some ridiculous ideas are floated, a few of which are very funny. All the while, tapes roll and the cameras run. “We’ve been getting grumpy for the last 18 months,” says Starr. (pictured left, Ringo Starr, Twickenham Film Studios, 7 January 1969)

In this context, it is extraordinary that dogged original director Michael Lindsay-Hogg repeatedly pushes the band on what this aiming at; what sort of concert are they going to do, where and how? Some ridiculous ideas are floated, a few of which are very funny. All the while, tapes roll and the cameras run. “We’ve been getting grumpy for the last 18 months,” says Starr. (pictured left, Ringo Starr, Twickenham Film Studios, 7 January 1969)

Peter Sellers turns up. He and Starr are to appear together in the Magic Christian film, the shooting of which begins at Twickenham after The Beatles have left the studio. It is an uncomfortable encounter. Sellers looks embarrassed by the heavy atmosphere and scuttles off. Also difficult is a visit from unctuous music publisher Dick James. Yoko Ono is there most of the time and no one questions her presence. McCartney says “It’s going to be an incredibly comical thing in 50 years’ time [when people say] they broke up because Yoko sat on an amp.”

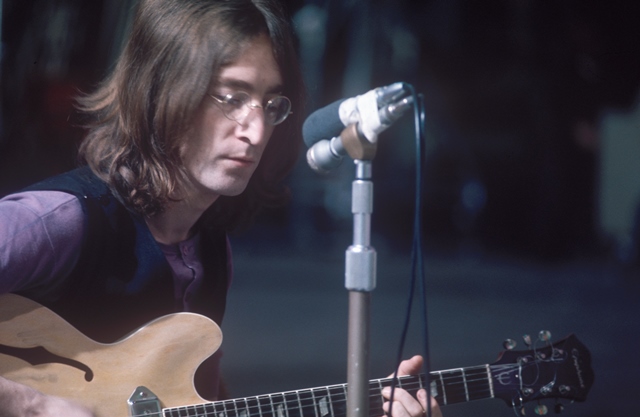

Though the directionlessness remains, the inertia dissipates after they arrive at Savile Row. Good humour is increasingly evident. Lennon livens up, engages and is very witty. Linda Eastman and her lively daughter are not a distraction, even when the latter (like Ono) fantastically has a go at singing (the band dynamics allowing Ono behind a microphone could hardly prevent the younger Eastman doing the same). Billy Preston comes on board: his and an increased presence from producer George Martin help it coalesce – despite not getting it together to rehearse what they are potentially going to play live on the Apple rooftop. When they get up there, the resultant 42-minutes is a wonder. The police response is hilarious. Watching the new Get Back is a joy. (pictured right, John Lennon, Twickenham Film Studios, 7 January 1969)

Though the directionlessness remains, the inertia dissipates after they arrive at Savile Row. Good humour is increasingly evident. Lennon livens up, engages and is very witty. Linda Eastman and her lively daughter are not a distraction, even when the latter (like Ono) fantastically has a go at singing (the band dynamics allowing Ono behind a microphone could hardly prevent the younger Eastman doing the same). Billy Preston comes on board: his and an increased presence from producer George Martin help it coalesce – despite not getting it together to rehearse what they are potentially going to play live on the Apple rooftop. When they get up there, the resultant 42-minutes is a wonder. The police response is hilarious. Watching the new Get Back is a joy. (pictured right, John Lennon, Twickenham Film Studios, 7 January 1969)

The background is tortuous. George Harrison, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr arrived at Twickenham Film Studios on 2 January 1969 to work-up what was conceived as a television special. Cameras were there under director Michael Lindsay-Hogg. He was familiar to the band as he had worked on Ready Steady Go! and directed their promo films for “Paperback Writer,” “Rain,” “Hey Jude” and “Revolution – the latter two made at Twickenham in late July/early August 1968. They had also made a series of promo films at Twickenham on 23 November 1965. The Beatles knew what this place was. As well as Lindsay-Hogg, an ever-stylish Glyn Johns was another constant, on hand to capture the audio.

George Harrison left the band on 10 January – as Starr had done the previous year. Harrison was back when the whole thing shifted to Apple’s Savile Row headquarters. Grand ideas for the TV special were scaled back and the band – with fifth Beatles Billy Preston on keyboards – played the rooftop on 30 January. After a little bit more recording the next day, that was that. Sessions for what became the Abbey Road album began on 22 February. That was issued on 26 September 1969. Apart from the “Get Back” single, the January adventure was put aside.

Nevertheless, while Abbey Road took shape the audio side of the January 1969 material was outsourced to Glyn Johns. His first go at a Get Back album (finalised on 28 May 1969) never came out. His next version (a master tape was made on 5 January 1970) was also shelved. In parallel, Lindsay-Hogg was finalising the Let It Be film, which premiered on 13 May 1970 (the band had rejected his first cut). The accompanying album had arrived on 8 May, the result of Phil Spector’s 13 March to 2 April 1970 work on the January 1969 tapes. Something had to be in the shops alongside the film release. (pictured left, Paul McCartney at Apple Studios, Savile Row, 25 January 1969)

Nevertheless, while Abbey Road took shape the audio side of the January 1969 material was outsourced to Glyn Johns. His first go at a Get Back album (finalised on 28 May 1969) never came out. His next version (a master tape was made on 5 January 1970) was also shelved. In parallel, Lindsay-Hogg was finalising the Let It Be film, which premiered on 13 May 1970 (the band had rejected his first cut). The accompanying album had arrived on 8 May, the result of Phil Spector’s 13 March to 2 April 1970 work on the January 1969 tapes. Something had to be in the shops alongside the film release. (pictured left, Paul McCartney at Apple Studios, Savile Row, 25 January 1969)

Thirty-three years later, the Let It Be… Naked album appeared. What Phil Spector had done was undone, remixed and rejigged. From this point, the albums The Beatles originally issued were no longer the last word. Inevitably, at some point, something along these lines was bound to happen with the Let It Be film. Its last UK TV broadcast was on 8 May 1982 and, since then and a few escapes onto legal VHS tapes, it’s done the rounds on bootleg VHS, laser disc, DVD and Blu-ray. Various official upgrades were made, but nothing was released. Odd bits were filleted for the 1995 Anthology series and the 2015 1+ DVD/Blu-ray set. On the audio side, a Let It Be Special Edition box set emerged in October 2021. It included Glyn Johns’s May 1969 Get Back album. Over all this time, the album and film of Let It Be were The Beatles equivalent of an endlessly long, winding road. Now it looks as if a line is drawn with what became the Let It Be film.

Qualms about the seemingly ceaseless messing with The Beatles’ recorded work are never far though. This feels different to, say, a needless Sgt. Pepper’s remix or even Let It Be… Naked. But with The Beatles, never say never as their organisation’s appetite for reconfiguration appears insatiable. However, this superb release will do just fine. Another point of view is unnecessary.

@MrKieronTyler