Monday Morning Thoughts: Why Prison Doesn’t Work – In One Graphic

Good Monday #GoodMonday

By David M. GreenwaldExecutive Editor

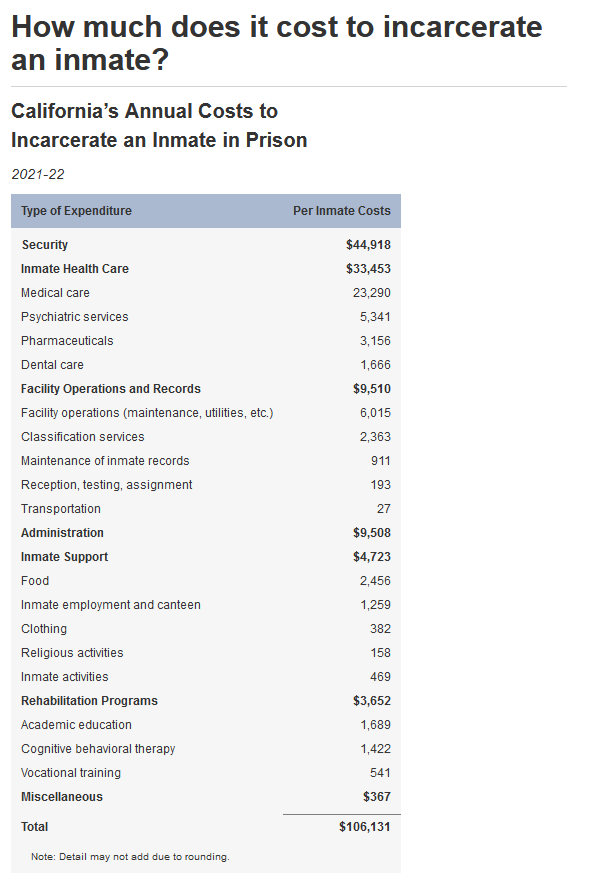

They say a picture is worth one thousand words—a good graphic might be worth even more than that. I pulled this graphic from CDCR because it shows the breakdown of the costs to incarcerate one person for one year in prison.

The number itself is absurd. It costs California around $106 thousand per year per incarcerated person. Think about that. That’s more than it costs for a year at Harvard. That’s 8 to 10 times more than we spent per pupil on K through 12. Imagine reinvesting that money into education, job training, housing, food, and mental health.

Once we start breaking down the costs, we see just how little we are actually getting from this expenditure. The two biggest costs are security (nearly $45K) and health care ($33.4K). Add in $9.5K for facilities, $9.5K for administration, and $4.7K (meager amount) for “inmate support” (food and clothing) and that leaves just $3652 for rehabilitation programs.

Once we start breaking down the costs, we see just how little we are actually getting from this expenditure. The two biggest costs are security (nearly $45K) and health care ($33.4K). Add in $9.5K for facilities, $9.5K for administration, and $4.7K (meager amount) for “inmate support” (food and clothing) and that leaves just $3652 for rehabilitation programs.

Budget is a statement of values. The fact that we spend nearly ten times the amount to incarcerate someone as we do to educate them is troubling. But even within the massive amount that we spend on incarceration, most of the money goes to security, administration and maintenance of the incarcerated rather than toward programs that could help them rebuild their lives.

There are a small number of people who pose a true threat to the safety of the community for whom there really is only one option—incarceration. But that number is very very  small.

small.

I just interviewed Akhi Johnson of the Vera Institute of Justice for an upcoming Podcast. One of the points he made, which has been made by so many other reformers, is if incarceration were the key to public safety, “the US would be the safest country in the world.”

Incarceration might temporarily protect the public at large from the small percentage of dangerous people and larger percentage of people who find themselves struggling with drug addiction or mental illness or trapped in poverty—but incarceration makes things worse often.

The stats speak volumes—fully 95 percent of those incarcerated will be released at some point in time. The number of actual life sentences are small. But our recidivism rate is still between 60 and 70 percent. That means that the system does little to stop the cycle of poverty and incarceration and instead exacerbates it.

And when we look at the spending, no wonder that’s the case.

In 1996, former President Bill Clinton ended welfare as we know it. He imposed caps on how long people could receive aid and food. So instead of the federal government or the states providing food to dependent families, the idea was move them into jobs. Never mind that real wages have stagnated over the last fifty years and their purchase power is greatly diminished.

Never mind that people—over half of whom lack a high school degree—face job insecurity, food insecurity and housing insecurity. We are more than happy—apparently—to replace welfare with prison fair.

Not only do we fail to take care of our incarcerated while they are in custody, but we make it impossible upon release for them to get themselves into a secure position. The vast majority of employers will not hire formerly incarcerated. And often parole agents will call places of work to check in on those still under supervision, putting them at risk for harassment and job loss.

We still give those released on parole just $200 in pocket money and a bus ticket to the county in which they lived at the time of their arrest—if you think about it, why would you want to send them back to the same environment that led them to prison? Most states legally require the formerly incarcerated to reside there as long as they are under supervision.

Most are not prepared for release. At one point, CDCR just had 200 beds in shelter for 10,000 homeless people released. And just four clinics for 18,000 or so released who were in need of serious psychiatric care, and a limited number of drug treatment programs for those who suffer from known drug addiction or alcoholism.

In other words, we house people in a prison where we spent 3.5 cents on the dollar on rehabilitative programs and then release people who are suffering from homelessness, mental illness, or drug addiction without the proper resources to deal with their trauma and substance abuse—and then we wonder why people go out and commit new crimes.

Prison may be harsh, but at least it’s three meals and a cot and crappy health care.

I understand those who argue if you can’t do the time, don’t do the crime. The problem is that we have made it impossible to get those people to a place where they don’t have to commit crimes to survive. And we are spending a boatload of money to do that.

The numbers here don’t lie—there is a reason why this system has failed.