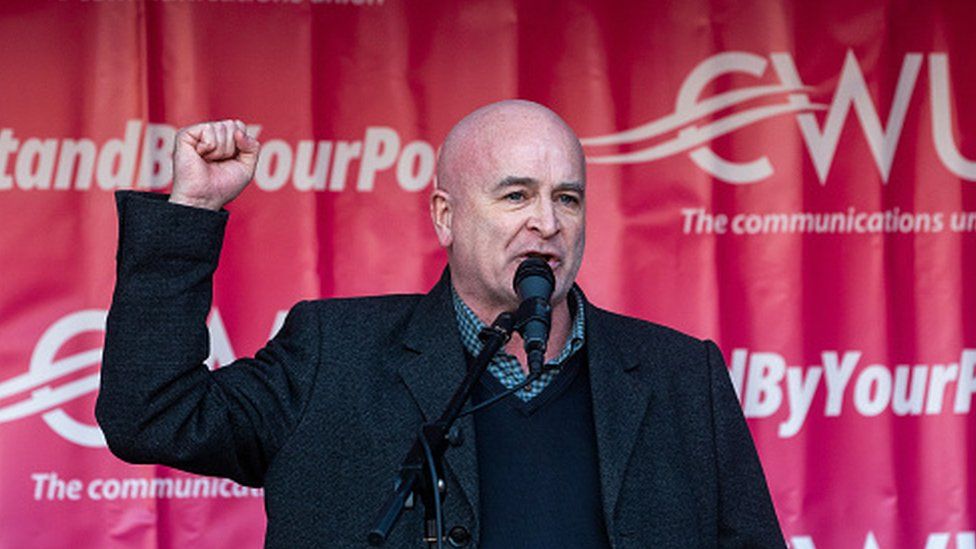

Mick Lynch: The union firebrand accused of stealing Christmas

Mick Lynch #MickLynch

Image caption,

RMT general secretary Mick Lynch has become a figurehead of the trade union movement

By Joshua Nevett

BBC Politics

One is a cynical grump whose cold-hearted plot to steal Christmas dampens the festive mood.

The other is Mick Lynch, the general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT).

When he announced a blitz of winter rail strikes last month, Mr Lynch denied being the mean-spirited green monster. “I’m not the Grinch, I’m a trade union official, and I’m determined to get a deal,” he said.

In unflattering media coverage, the bogeymen comparisons veer from the Grinch to the Hood, the bald-headed, bushy-eyebrowed baddie from 1960s puppet TV series.

Welcome to the world of Mick Lynch, where adoring fans and outspoken critics form orderly queues to take selfies with or pot shots at the union boss.

![]()

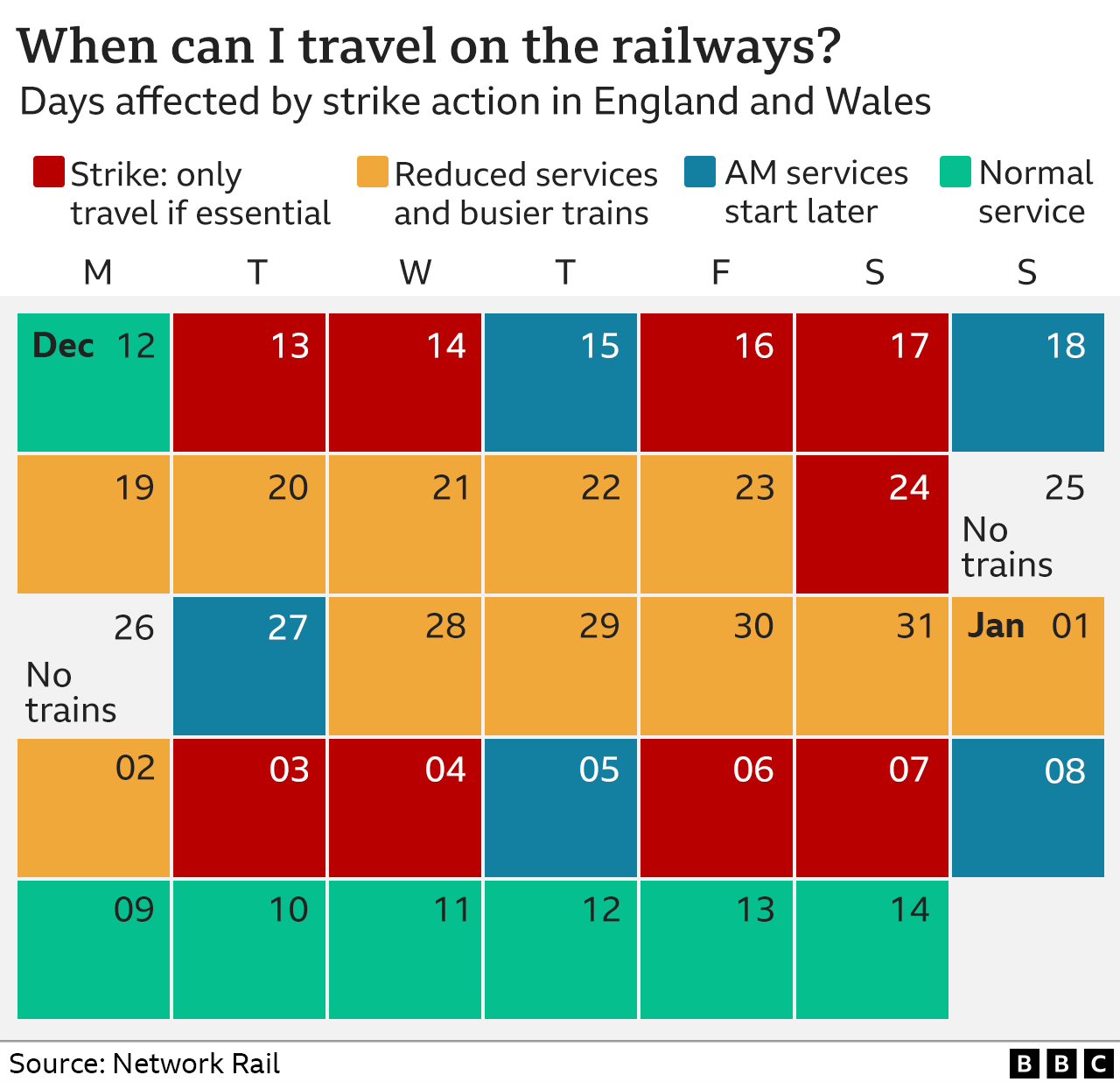

Seeking a deal on jobs, pay and working conditions, the RMT has escalated its industrial action, bringing the total number of strike days to 12 over the festive period.

As the RMT’s top official, Mr Lynch is the chief spokesman and negotiator for the union, which represents about 80,000 members from the transport industry. Some of those members elected Mr Lynch to that position in May 2021, giving him a mandate to protect and further their interests.

In a year of heightened industrial strife, this influential role in a critical sector has become a matter of national interest, along with the personality of the career trade unionist who wields its power.

Known for his meme-friendly tirades in front on TV cameras, Mr Lynch has the kind of name recognition unattainable to most union leaders.

For those who haven’t heard of him, his warm reception at a recent rally for postal workers would give you few clues as to why he was once labelled “one of the most hated men in Britain” by the Daily Mail newspaper.

In a packed Parliament Square, hand-shakers and selfie-takers are sucked into his orbit. Their problems are ours, says Mr Lynch, whose dad was a postal worker.

Never mind the Grinch “nonsense”, he says. Seen through his lens, Mr Lynch is supporting workers in their struggle against an exploitative government and a greedy super-rich.

“I’m a working-class bloke who’s elected by the ordinary men and women of the railway to articulate their case and represent them,” he tells the BBC.

Energised by a friendly crowd, Mr Lynch saves his most venomous invective for his stump speech, delivered after walking on stage to chants of “RMT, RMT”.

“All the right-wing media, all the commentators, they all hate us,” he says. “Why do they hate us? Because they’re scared of us.”

Image caption,

Mr Lynch posed for photos with striking postal workers

Them-versus-us has been a common theme in Mr Lynch’s life. The son of Irish-Catholic parents, he grew up in London during the Troubles in Northern Ireland and the industrial discord of the 1970s. His parents moved to the capital during World War Two and he was raised on a council estate in Paddington, in what he’s described as “rented rooms that would now be called slums”.

At 16, he left school and trained to be an electrician, before finding work in construction.

As industrial action ebbed and flowed in the 1980s, Mr Lynch became involved in a breakaway union with a mark against its name. He was secretly blacklisted by constructions companies, leaving him struggling to find work for years.

When the blacklist was exposed decades later, Mr Lynch was compensated with a cheque for £35,000, a copy of which hangs framed on his office wall today.

In the meantime, Mr Lynch found work on the railways with Eurostar and founded an RMT branch for its employees. From there, his rise to the top of the RMT was “almost an accident of history”, says Gregor Gall, a professor of industrial relations.

Image source, Getty Images Image caption,

Mick Cash (C) retired after six years as general secretary of the RMT

With the RMT riven by factionalism, Mr Lynch’s predecessor as general secretary, Mick Cash, retired in 2020 after six years in the job, blaming a “campaign of harassment” by elements of the membership. Mr Lynch was appointed acting general secretary, but soon stood down himself, accusing senior union members of “bullying” and creating “an intolerable, toxic atmosphere”.

Despite this, Mr Lynch returned and won election to the role permanently in May 2021.

“The executive is now united around him,” says Professor Gall.

Mr Lynch was elected with the support of Broad Left, a socialist group in the union.

Conservative MP Chris Loder, who was an RMT member when he worked in the rail industry, says Mr Lynch has a “dependency” on the group, which is “egging him on” to take a more militant line on strikes.

Well-paid RMT officials like Mr Lynch – who says he earns £84,000 a year – are “leading the charge for ideological reasons”, Mr Loder says. He says Mr Lynch is “between a rock and a hard place” because “most sensible members of the RMT do not agree with the level of strike action he’s taking”.

![]()

Meanwhile, there have been signs of waning public support. Last month, a YouGov poll found some of the RMT’s winter rail strikes were opposed by 47% and supported by 41% of those surveyed.

Will the Christmas rail strikes dint Mr Lynch’s popularity?

Former shadow transport secretary and Labour MP Andy McDonald doesn’t think so. Whenever they crossed paths, Mr Lynch “struck me as a rock-solid, working-class fella who was very clear about what he believed”, Mr McDonald says.

He says he had a positive experience working with him and others on plans to nationalise the railways under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party. Like the left-wing MP, Mr Lynch is seen as straightforward and authentic by his admirers, a working-class firebrand for the TikTok age.

Now Sir Keir Starmer has shifted Labour to the right, Mr Lynch has filled a void on the left. “There’s clearly a constituency for that,” says Professor Gall.

At the Parliament Square rally, My Lynch appeals directly to that constituency, as Mr Corbyn watches on backstage.

“I’m saying to Starmer and Reeves and anyone else who seeks to represent working people: whose side are you on?”

Image source, Getty Images Image caption,

Mr Lynch challenged the Labour leader to join him on the picket line

Pointing indignantly to Parliament over the road, My Lynch challenges the Labour leader to “come over here and get on our picket line”.

Mr Lynch is channelling the disaffection felt among workers, just as it was during the 1978-79 Winter of Discontent. Then as now, widespread strikes paralysed the economy, as the government wrestled with high inflation.

From one perspective, it was a time of chaos, made worse by muscular trade unions with too much power.

Not so in Mr Lynch’s world.

“We had a more balanced society,” he says. “The bosses couldn’t get away with whatever they wanted.”

Raising his voice to be heard over the din of angry strikers, he adds: “We need that now.”