Matthew Perry was much more than an addict. Don’t let his death overshadow that

Matthew Perry #MatthewPerry

When I heard the news about Matthew Perry, there was a moment of quiet, of inner collapse, like the moment a soufflé gives up on itself. I wasn’t thinking about Friends, and without wanting to sound like an emotionless sociopath, it’s rare for the death of a celebrity I don’t know to prompt anything more in me than the sadness felt about the loss of any life.

But I was thinking about his life viewed through the lens of addiction, and what he carried with him, and how it never left him. How his friends and family must have felt, having wanted the best life for him, having been caught in the maelstrom of chaos only to see his life snuffed out at the age of just 54. It is a feeling that only those who live with addiction themselves, or who love those who do, will know.

About 10 years ago, my late husband Rob told me something earth-shattering, something that finally made sense of the increasingly bizarre behaviour I had been noticing. He seemed constantly out of money despite working, he’d fall asleep when we visited people, he would spend days sick in bed, unable to move, and he’d go to the corner shop at odd times of night. This happened over months, then years, and when I finally snapped and said he had to tell me what was going on, he confessed that he was a heroin addict and had been for years.

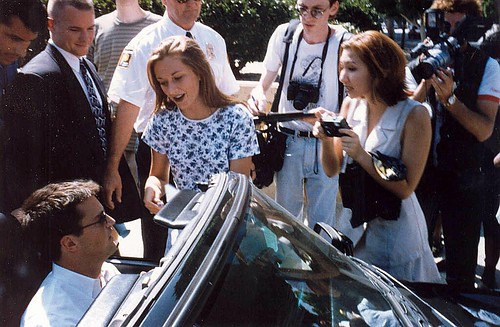

Poorna Bell’s husband Rob

I remember rushing downstairs to my study and hyperventilating. The only way I can describe the sensation was that it felt as if the contents of my body were now on the outside. People often say in scenarios like this that the partner “must have known”, but I truly didn’t know. I had no idea what heroin addiction looked like, and I certainly didn’t believe that the man I had married was lying to me. I knew something was wrong, but since mind-reading doesn’t exist, I couldn’t force Rob to tell me until he was ready.

I made the decision to help him get clean and to provide love and support. It changed everything I thought I knew about addiction. Previously I had moralised about it from on high, a strong subscriber to the “if they loved you they’d just stop” philosophy, not at that time understanding anything about how addiction works.

In one of the first support group meetings I went to in the early days of helping Rob, I was told addiction results in one of three things: recovery, jail or death. Everyone, whether recovering addicts of longstanding, or loved ones who’d been going to meetings for many years, agreed with this.

I have written a lot over the years about suicide prevention (it is how Rob died), depression (which he had, chronically) and addiction, and, while we have moved the needle in terms of how we understand and talk about mental health, I don’t know how much we have progressed when it comes to addiction. We still ask: why them and not me? Why can’t they just do what I do? Instead of thinking: what is this formidable thing that will compel a person to do something that damages them, to the point where they may lose everyone in their life who loves them?

Rob died by suicide, but addiction played an enormous role in how he got to that point. There are statistics that show that when depression is also present, particularly if it is chronic, and particularly for men, it can be a lethal combination. Not only does it carve out the things you may value about yourself, but it replaces them with shame and guilt, and then, at the end of a long, dark tunnel, offers you a temporary solution. That cycle continues over and over again.

Floral tributes for Matthew Perry outside the apartment building which was used as the exterior shot in the TV show Friends, New York 29 October 2023. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

The best insight I had to this was in a speech Rob showed me, which he delivered when asked to chair a Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meeting. First he quoted from the NA manifesto: “An addict is a man or woman whose life is controlled by drugs. We are people in the grip of a continuing and progressive illness whose ends are always the same: jails, institutions and death.”

Then, he added: “This statement both resonates and rankles. I struggle to agree with the idea of my addiction as an ‘illness’. Is this the last of my pride? Or am I turning my back on an easy excuse? It doesn’t really matter.

“Growing up in a devoutly Christian household, the passage in the New Testament that meant the most to me was Jesus, a man, alone and about to die, crying out on the cross ‘My God, why have you forsaken me?’

“Drug addicts don’t live in hell, that bustling metropolis of souls united in torment, but hang helpless on a lonely hill, facing a tomorrow over which they have lost control, of more lies, shame, betrayal – a tomorrow of abasing themselves once more before a god whose only currency is death, but who cannot be denied or abandoned without great suffering.”

Over the next week, many things will be said about Perry. I imagine they will not all be of his choosing. In his recent memoir, he wrote about trying to help other addicts, which included setting up a sober-living facility in Malibu, and said: “When I die, I know people will talk about Friends, Friends, Friends … but when I die, as far as my so-called accomplishments go, it would be nice if Friends were listed far behind the things I did to try to help other people.”

It reminded me of how strongly Rob felt about helping other people. How far he would go if someone needed it. How he’d help out at Crisis, the homeless shelter, over Christmas, to be there at the point of the year when the disparity between the have and have nots was at its most acute.

It reminded me that when addiction is part of a person’s life, it is used to define who they were, when the reality is that, like everyone, they had good and bad parts, and the stigma of it should never be used to scrub away the good. What a shame, what a waste, we say. And while it is, it’s important to not lose sight of the very best parts of them. Today, I am thinking of anyone who heard this news and felt the fluttering of a ghost, or the hairs on the back of their neck rise.

A version of this piece first appeared on As I Was Saying, Poorna Bell’s substack newsletter. Poorna Bell is the author of four books, including Chase the Rainbow

In the UK, Action on Addiction is available on 0300 330 0659. In the US, call or text SAMHSA’s National Helpline is at 988. In Australia, the Opioid Treatment Line is at 1800 642 428 or call the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline on 1800 250 015

Comments on this piece are premoderated to ensure discussion remains on topics raised by the writer. Please be aware there may be a short delay in comments appearing on the site.