Jean-Luc Godard, daring French New Wave director, dies at 91

Godard #Godard

Jean-Luc Godard, the defiantly iconoclastic and stylistically adventurous filmmaking giant who rose to prominence as part of the French New Wave movement in the 1960s, has died.

He was 91.

Godard’s death was confirmed by French President Emmanuel Macron, who praised the director for having “invented a resolutely modern, intensely free art.”

“We are losing a national treasure, a look of genius,” Macron wrote on Twitter.

Godard upended filmmaking conventions at every turn. He delighted, provoked, and sometimes puzzled audiences with art-house classics like “Breathless” (1960), “Band of Outsiders” (1964) and “Alphaville” (1965).

He experimented with handheld camera work, jarring “jump cuts” and other radical techniques that freely mixed fiction and documentary styles, inspiring legions of filmmakers around the world to boldly defy artistic traditions.

“A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end,” Godard once said, “but not necessarily in that order.”

Godard, along with peers such as Francois Truffaut and Eric Rohmer, pioneered a movement known as the French New Wave (or La Nouvelle Vague), an explosion of innovative, narratively loose-limbed and wittily self-reflexive movies.

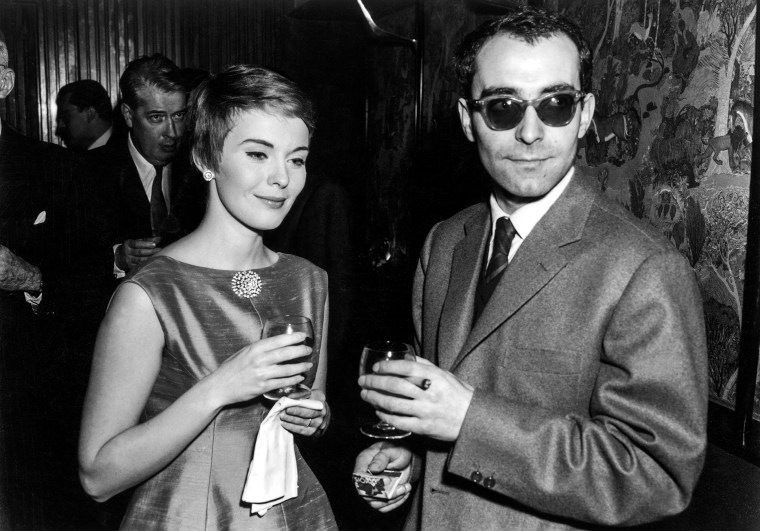

American actor Jean Seberg and Jean-Luc Godard in 1960 in Paris.Keystone-France / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

American actor Jean Seberg and Jean-Luc Godard in 1960 in Paris.Keystone-France / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“Breathless,” Godard’s first feature-length film, embodied the verve of the French New Wave: jazzy, rough-edged, fearless. Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg starred, but Godard was practically an invisible third character, leaving his imprint on every frame.

He started out as a critic at the 1950s. In daring, highly influential work for the journal Cahiers du Cinéma, Godard dismissed the staid traditions of European art cinema and advocated instead for American directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks.

Godard was known for his leftist politics, and his views — informed in part by his study of Marxism and existentialism — shaped many of his early films and occasionally made him a magnet for controversy.

In recent years, Godard continued to work steadily, exploring the new possibilities of digital technology in artistically rigorous and elusive works like “Film Socialisme” (2010), “Goodbye to Language” (2014) and “The Image Book” (2018).

“Godard is a director of the very first rank; no other director in the 1960s has had more influence on the development of the feature-length film,” the late critic Roger Ebert wrote in 1969. “Like Joyce in fiction or Beckett in theater, he is a pioneer whose present work is not acceptable to present audiences.”

“But his influence on other directors is gradually creating and educating an audience that will, perhaps in the next generation, be able to look back at his films and see that this is where their cinema began,” Ebert added.

Jean-Luc Godard was born on Dec. 3, 1930, to an affluent French-Swiss family in Paris; his father was a doctor who ran a clinic on the Swiss side of Lake Geneva. In time, Godard rebuffed the bourgeois comforts of his upbringing, lurching towards views that rejected the status quo.

He studied for a degree in ethnology, participated in countless conversations at Parisian student cafés and soaked up the countercultural scene that emerged after World War II. The young artist’s cerebral interests would eventually lead him to art cinema.

In infectiously enthusiastic writing for Cahiers du Cinéma, Godard and his New Wave peers made what was then an unorthodox argument: Hitchcock, Hawks and other American studio filmmakers were artistic giants on par with the European masters.

The young critic — like many of his fellow writers for Cahiers — soon turned to making his own films.

Godard’s reverence for U.S. commercial cinema was plain to see in “Breathless,” where a freewheeling sensibility drawn from European neorealism mixed with the iconography of midcentury America: guns, fedoras, cigarettes and tabloid newspapers.

He was prolific, making at least a film a year in the ’60s, including art-house essentials like “A Woman Is a Woman” (1961), “Contempt” (1963), “Pierrot le Fou” (1965), “Masculin Féminin” (1966) and “Week-end” (1967).

He entered a confrontational and politically militant period in the ’70s before returning to what some critics considered a more conventional style in the ’80s.

Godard’s films are considered key influences on liberated, rule-breaking directors such as Martin Scorsese, Bernardo Bertolucci, Steven Soderbergh and Quentin Tarantino, as well as many experimental talents working outside the Hollywood system.

He was married twice, to Anna Karina and then Anne Wiazemsky, both actors who starred in many of his films.

“The seven and a half films that [Karina] made with Jean-Luc Godard constitute, arguably, the most influential body of work in the history of cinema,” Filmmaker magazine wrote in 2016.

He later began a romantic relationship with Swiss filmmaker Anne-Marie Miéville, who was with him at the time of his death.

In the course of his career, Godard received accolades such as the Venice Film Festival Golden Lion in 1983 and an honorary Academy Award in 2010. The Oscar was inscribed: “For passion. For confrontation. For a new kind of cinema.”