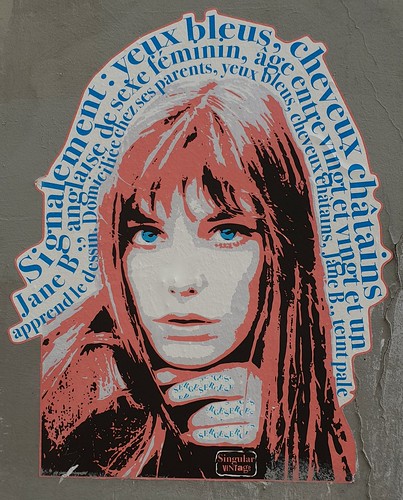

Jane Birkin made the simple things feel luxurious

Jane Birkin #JaneBirkin

Comment on this storyComment

Jane Birkin, who died Sunday at 76, was a quixotic fashion muse. Unlike society figures such as Nan Kempner or Loulou de la Falaise, who landed on best-dressed lists because they had scores of the most rarefied couture, Birkin preferred khakis from Army surplus stores, men’s jackets and baskets as handbags.

The story of how she came to inspire the most famous handbag in fashion history — the Hermès Birkin bag — paints the picture of her peculiar influence well. The actress and singer was upgraded to first class on a flight from Paris to London in the 1980s, with one of the wicker baskets she used as a purse in tow. (She wore them from the 1960s onward, pairing them with see-through crochet minidresses as well as jeans and T-shirts.)

When she put her basket in the overhead compartment, as her retelling went, her stuff spilled onto the floor. She told her seatmate, Jean-Louis Dumas, who was chief executive and artistic director of his family’s brand, Hermès, that she’d had trouble finding a good weekend bag, and he had the atelier rework their existing haut à courroies into something more streamlined.

Such is the Birkin mystique: Her pastoral idiosyncrasy, picked up at a London street fair, inspired the pinnacle in luxury design and desire, which sells for upward of $8,500. She knew how to make the simplest things feel special, even extraordinary in a private way, which was what drew luxury houses like Hermès to her, as well as our great modern designers, such as Hedi Slimane, A.P.C.’s Jean Touitou and Martin Margiela. (The punchline: Birkin rarely carried the bag because of her tendinitis. Part of her attraction to men’s blazers was their enormous pockets, perfect for stuffing, and in her last years, she usually wore belt bags and straw market bags. One of her later partners, filmmaker Jacques Doillon, eventually ran over the original basket with his car.)

The house of Hermès shared a statement Sunday afternoon on Birkin’s passing. “With a shared sensitivity, we grew to know each other, we discovered and appreciated the extent to which Jane Birkin’s soft elegance revealed an artist in her own right, committed, open-minded, with a natural curiosity of the world and others.”

Born in 1946 in London, Birkin became synonymous with “French girl style” — a term now so overused it feels meaningless, but a study of Birkin’s look reinforces why it endures. In the 1960s, she was a Swinging London heroine of psychedelic cinema, winning the lead role in the French film “Slogan” alongside Serge Gainsbourg. It was in that film that Birkin would come to know Gainsbourg, and the world would come to know her charmingly broken French. (She was cast in the film despite not speaking the language.)

Her appearances alongside the Lothario Gainsbourg, in crochet dresses with her nipples exposed and her little basket on her arm, codified her as a paradoxical ingénue: childlike and boyish, yet somehow wildly sophisticated. Her duet with Gainsbourg, “Je t’aime moi non plus,” released the same year as “Slogan,” embodies her shocking appeal: Her voice is breathy and at times pip-squeaky, eventually succumbing to orgasmic whispers.

With Gainsbourg, she had one child — Charlotte, who, along with her younger sister, Lou Doillon, is renowned as an actor and muse; her first daughter, Kate Barry, died in 2013 — and although they never married, she would be associated with Gainsbourg for the rest of her life. (He died in 1991.)

It was an alliance she encouraged herself; when I first interviewed her in 2016, she brought up Gainsbourg and his unsavory reputation without my even asking, saying: “I have to defend him. And so I will.” Gainsbourg struggled with alcohol addiction, once demeaning Whitney Houston to her face on live television in the 1980s, and his eager provocations about sex made him a legend in France but reviled elsewhere. In 1984, he recorded “Lemon Incest” with his and Birkin’s daughter, Charlotte, with both appearing half-dressed in bed in the music video. (It spent 10 weeks on France’s Top 10 chart.)

Birkin seemed to understand his reputation but also saw how, in a country like France in the 1960s and ’70s, he represented a sublime amount of freedom. Her ease with her strange sexual appeal, at first, and later her unstudied casual style, that seemed so quintessentially French. She had a mind that could seem, in passing conversation, simply quirky, then, a flash later, delightfully original. She thought women were at their prettiest after 40, she told me, saying that her daughters weren’t old enough yet but would then “probably be at their most sumptuous.”

By the 1980s, when her romance with Gainsbourg ended and her relationship with Doillon began, her style had shifted from mod, glam and libidinous to understated and casual. Gainsbourg had always told her “to lick your lips and toss your hair back,” she told me last year. “And one day, I said, ‘No, I won’t do that anymore!’” She adopted a uniform of jeans, men’s cashmere sweaters, scoop-neck T-shirts with overstretched necklines and workmen’s trousers, with men’s jackets thrown overtop. (To view the look in its most glorious form, see Agnès Varda’s meta-tribute, “Jane B. par Agnes V.”)

It was this sensibility that has inspired nearly every designer of the past 30 years, because her way of wearing, say, oversize men’s pants and fastening them with the right belt to make them paper-bag-like, was so original, so unstudied and cool. She came to embody the often-discussed but little-understood line between fashion and style: Style is a representation of pure originality, of some interior strangeness and individualism.

For all her influence, Birkin only did one collaboration — last fall, with A.P.C.’s Touitou. The pieces were almost alarmingly simple, drawn from that uniform of worn basics. For anyone who knows Birkin solely through old pictures posted to Instagram and fashion-magazine throwback stories, they might have been surprised, expecting Proust’s madeleines and instead getting plums in the icebox.

But Birkin, Touitou texted me Sunday while sailing off the west coast of Italy, “had that sense of perfect proportions that only few people have. Her casualness was extremely precise.” She was exacting in how fabrics felt against her body, over her arms and legs as she moved through the world, whether she was attending movie premieres or buying fruit at markets. What woman doesn’t envy understanding her own desires, her own comfort?

The truth is that the fashion world cannot exist without such characters — those who see something we all see, all wear, and go about our days assuming is just to be worn and thought about one way, but who somehow see that thing as a funky possibility. Birkin reminds us that style is not merely a frivolous chase to all adapt the same agreed-upon look; the most lasting legacies begin with one person with outrageous, delicious courage who cannot help but express herself.

correction

A previous version of this article incorrectly said that Jane Birkin and Jacques Doillon had married. They did not. This version has been corrected.

Gift this articleGift Article