History’s most incredible drag queens and kings

Noirs #Noirs

Thanks to Ru Paul, drag has never been more popular – so why isn’t its rich history better known? It’s time we saw more novels, plays and films taking the artform seriously, suggests Matt Cain.

F

From RuPaul’s Drag Race to live cabaret and theatre shows, drag has never been more popular. In case you’ve been hiding under a wig block for the last 10 years, drag is the art of gendered impersonation, with performers exaggerating and heightening aspects of femininity or masculinity for the sake of entertainment.

As it takes the world by storm, drag is changing our language, our ideas about gender, and even the way we see ourselves.

More like this:

– The gay love affairs being uncovered

– Is Drag Race good for drag?

– Has culture finally embraced LGBTQ+ people?

I’m a huge fan of drag, so much so that it has inspired my latest novel, Becoming Ted. It’s a contemporary story about a 43-year-old man who’s dumped by his husband but takes this as an opportunity to pursue his long-suppressed dream of becoming a drag queen – in the process discovering an inner strength he hadn’t known existed. For me, drag can be about self-discovery and self-fulfilment. I’ve also put it at the heart of my first theatre project, which hasn’t yet been announced but will open in Manchester in July.

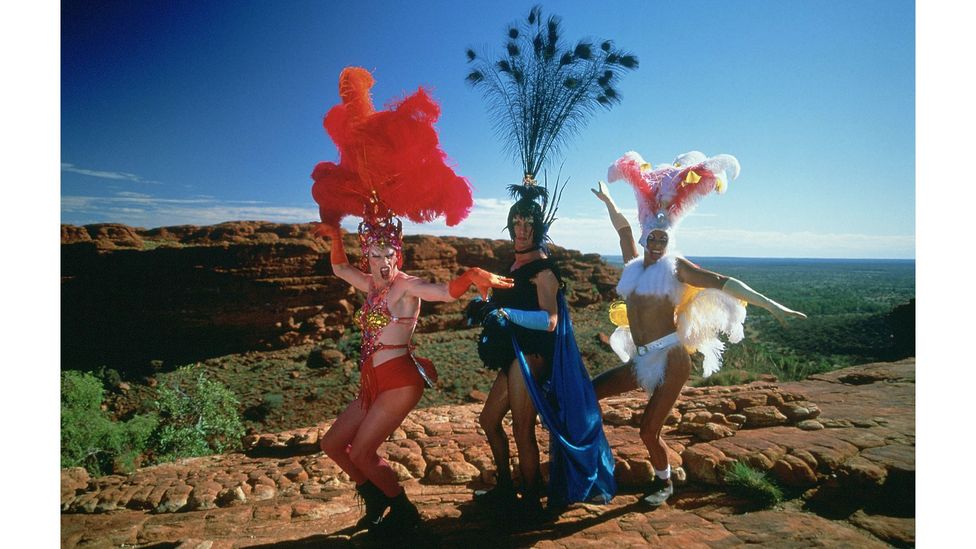

Priscilla, Queen of the Desert is one of the most famous drag-centred films – but there should be more (Credit: Alamy)

But I’m shocked to discover that there are very few other drag-themed novels, plays or films scheduled to come out over the next year. To use drag vernacular, if the library’s open, there aren’t many books to read. In particular, the art form has a rich history that is not as widely known as it should be – something that, as we enter LGBT+ History Month in the UK, feels particularly glaring.

For years, despite drag’s ubiquity in popular culture, it has been poorly represented in the narrative arts. Other than the musical Everybody’s Talking About Jamie and the TV series Pose (which, arguably, focused much more on the trans experience), you’d have to go back to 1990s films The Birdcage and Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, and 2003’s Kinky Boots (as well as its stage offshoot), to find high-profile stories that centre drag – and even then, it’s predominantly used as fun window-dressing for stories about the gay experience and its clashes with straight culture, or merely as a comedic device. But drag can be so much more; its transformative power presents writers with a unique opportunity on the level of both plot and characterisation.

Why drag gets ignored by writers

So why haven’t more writers been inspired? Divina de Campo, runner-up on the first season of RuPaul’s Drag Race UK, argues that drag has been the victim of cultural snobbery: “Because drag is rooted in comedy it gets treated like much of the rest of comedy, in that the work isn’t seen as serious or rather worthy. Drag pulls all art forms together – singing, dancing, acting, costuming, creation, writing, directing – but because it’s so often funny it’s seen as less somehow.”

Drag can also be subversive – and in particular can challenge gender stereotypes. “Drag can work on a deeper level, challenging expectations, social constructs, gender norms and identities,” continues de Campo. “That’s what my drag is about; doing and being what you want rather than what we’ve been conditioned to do and be… That makes the world too complicated for some people to even contemplate so they dismiss and deride it.”

Drag’s potential to subvert and disrupt is at the heart of the gloriously anarchic show Sound of the Underground, currently playing at London’s Royal Court Theatre, which is part-cabaret, part-political manifesto. Writer Travis Alabanza brings together several of London’s most exciting drag performers, all of whom put queerness at the centre of their work. It’s a long way from the pantomime dame. And it serves as a reminder that drag has always been closely associated with gay – or queer – culture.

Jacob Bloomfield is a Brooklyn-born historian who’s currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Konstanz in Germany, performs under the drag name Cupcake, and has written the upcoming book Drag: A British History. He tells BBC Culture: “Just as the genre of disco – which, like drag, is often associated with gay fans and artists – has been dismissed and even openly derided, drag too has often been dismissed. There is bigotry at play here.”

Fanny and Stella, aka Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park, were 19th-Century drag queens whose story and infamous trial was the subject of a 2013 non-fiction book (Credit: Alamy)

This bigotry has helped suppress from the mainstream historical record a whole queer subculture. And there are some compelling real-life stories that have been all but forgotten – that would surely make for brilliant novels, films, plays or otherwise.

For example, there’s John Cooper, the 18th-Century Englishman who dressed up as his drag alter ego Princess Seraphina and frequented London taverns known as “molly houses”, flaunting himself through the streets with a remarkable degree of openness for a time when gay sex was punishable by execution. Cooper is widely accepted to be the first drag queen in English history – sorry, herstory – or at least the first man for whom dressing up as a female alter ego was a key part of his identity.

Then in 1880, a drag ball took place at the Temperance Hall in Hulme, a district of Manchester. This was attended by 47 men, half of whom were dressed in women’s clothing, all of whom gained access by whispering the code word “Sister”. But the venue was raided by the police and all the men were arrested, prosecuted, and named and shamed in the press. Many of them were ruined. Imagine telling this story to modern-day audiences – imagine the empathy it could ignite, the emotional impact it could make.

Despite fierce persecution, drag culture blossomed around the world. In Berlin between the late 19th-Century and the 1930s, countless cross-dressing balls – known as Urningsballs or Tuntenballs – took place at various venues. The star queen of the scene was Hansi Sturm, whose act as Miss Eldorado culminated in him throwing his fake breasts into the audience.

In the US, the first person known to describe himself as a “queen of drag” was William Dorsey Swann, a former slave born in Maryland. In the 1880s, Swann hosted several drag balls in Washington, DC, at which he’d be accompanied by his partner, Pierce Lafayette. But after a police raid in 1896, Swann was convicted and sentenced to 10 months in jail.

It was during the early days of these balls that the term “drag” started to be used, although its origins are uncertain. It may have been inspired by the dresses worn by male performers wanting to exaggerate their expression of femininity, wearing dresses that were so heavy they literally needed dragging across the floor.

One story that is widely known is that of 19th-Century English drag queens Fanny and Stella, which was turned into a 2013 bestselling non-fiction book by Neil McKenna – and subsequently, a stage musical. Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park spent years dragging up to perform and sell sex on the streets of London. But in 1870 – after a wild night at the Strand Theatre – they were arrested and charged with conspiracy to commit sodomy. The trial whipped up public outrage, although Boulton and Park were eventually found not guilty because of a lack of evidence that sodomy had occurred.

New Yorker Gladys Bentley was a pioneering drag king and a key figure in the 1920s Harlem Renaissance (Credit: Alamy)

McKenna believes that the trial captured the public’s attention because: “there were all kinds of anxieties about masculinity, about decline, about the shrinking of Empire, about effeminacy, and a lot of stuff about women not being submissive or invisible anymore. Drag was seen as a manifestation of sodomitical behaviour, of effeminacy, of degeneracy.”

But even this story very nearly stayed buried as a historical footnote. “I struggled to find a publisher,” McKenna reveals. “And when I finally got Faber to publish it, certain phrases had to be cut from the book because they were considered too rude and too improper to publish.”

Drag kings as well as queens

If little is known about the drag queens of the past, even less is known about drag kings – or women impersonating men. And they’ve been almost entirely absent from the narrative arts, other than in the novels of Sarah Waters, most notably Tipping the Velvet, which was adapted into a popular BBC series back in 2002.

I spoke to Mo B Dick, drag king and co-creator of the website dragkinghistory.com. He traces the roots of drag king culture back to the 1660s, when women were first allowed to perform on the English stage. One of the first female playwrights, Aphra Behn, created several male roles that were meant to be played by women. “She specifically wrote ‘breeches roles’ for political reasons,” explains Mo B Dick, “so she could have her voice heard in this way, talking about politics and social mores. That was unheard of for women!”

One woman who excelled at playing breeches roles was Mademoiselle de Maupin, who was born in Paris in 1673. She was a gifted swordswoman, possessed of a fiery temperament, and known for having passionate affairs with both men and women. Her dramatic life – which included convictions for kidnapping and arson – came to an end at the age of just 33.

Les Rouges et Noirs were a hugely successful early 20th-Century drag troupe whose story was told in the film Splinters (1929) (Credit: Alamy)

Another was Charlotte Cushman, who was born in Boston in 1816. Cushman became one of America’s most popular actresses, before moving to Rome, where she set up a household populated solely by female artists. Her personal papers are housed in the US Library of Congress and reveal that all her romantic and sexual relationships were with women.

But it wasn’t until the late 1800s that drag king culture took on the form we recognise now. Gladys Bentley was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, an out-and-proud black lesbian entertainer known for wearing a white tuxedo and top hat and performing songs with bawdy lyrics in speakeasies and underground jazz clubs.

Mo B Dick defines drag king culture as being “about usurping male power and privilege” and adds that this is precisely why so many people found it unsettling – and continue to do so. He makes the point that today, drag kings are nowhere near as popular as drag queens: “Men putting on a dress is comedy, women putting on a suit is still considered threatening. So I think it’s more transgressive and makes people more uncomfortable for women to be in male drag. That is, people who want to uphold PMS – Patriarchy, Misogyny and Sexism.”

Perhaps another reason the history/herstory of drag artists isn’t more celebrated – in the way that historical figures in the fields of acting, writing, art or music are – is because drag’s roots are firmly in working-class culture; the figure of the drag queen as we understand it took shape in music hall in the UK and vaudeville in the US. As Jacob Bloomfield points out, “Working-class entertainment has often been dismissed as being not artistically credible.”

As an example, in his upcoming book Bloomfield discusses what happened in 1975, when an attempt was made to erect a blue plaque to commemorate Arthur Lucan, whose “Old Mother Riley” theatre act had made him a household name. A fierce debate erupted in the Greater London Council, with the Tory councillor representing Chelsea arguing that Lucan “in no way measures up to the criteria for a blue plaque and merely serves to lower the standards applicable in a misguided effort to curry popular favour.” But Lucan’s supporters won the debate, and a blue plaque dedicated to the actor was installed at his former home in Wembley.

However McKenna raises a slightly different point as regards drag and class, noting that the early days of drag culture in fact brought together people from different classes. “Drag was essentially working class but I think it was also classless. And cross-class interactions were taboo. If you read the Oscar Wilde trials, what you come across is the absolute outrage, horror and incredulity that Oscar Wilde could sleep with an unemployed stable boy, an unemployed valet.”

(Credit: Headline Review)

But despite this, Bloomfield stresses how at various points in history drag has crossed over to the cultural mainstream. Contrary to popular belief, the popularity of drag didn’t begin with RuPaul’s Drag Race. He mentions the 1929 musical comedy film Splinters, which told the real-life story of touring drag troupe Les Rouges et Noirs – and was so successful it spawned two sequels. And he quotes two different sources a century apart to show how drag has had huge currency at different times: an article published in The Times on 31 May 1870 which suggests that “in another year or two ‘drag’ might have become quite an institution, and open carriages might have displayed their disguised occupants without suspicion.” And the author Gilbert Oakley, who wrote in his book Sex Change and Dress Deviation in 1970; “In Great Britain today female impersonators are enjoying a vogue unparalleled since the introduction into music hall and pantomime of the comic dame.”

Certainly, today, we are living in another age of drag ubiquity, with drag queens in particular becoming international celebrities. But the stories really exploring what makes drag so fascinating – and in particular the stories of how the art form got to where it is today – are not being told. Why is that? “I would mostly put it down to cultural amnesia,” says Bloomfield, “and the sense that we in the present like to think that we are so much more knowledgeable, open, and aware than people in the past; that our lifestyles, interests, etc have no precedence.”

Whether or not my novel or musical gain critical respect, I hope they at least encourage the public to reflect on why drag is so meaningful to people and our culture. By telling contemporary stories about the impact the art form can have on human lives, I hope they encourage people to ask questions about its history/herstory. Because – not many people know this – but drag has been changing lives for centuries.

Matt Cain is a patron of LGBT+ History Month. His novel Becoming Ted is out now, published by Headline Review.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.