‘He has saved countless lives’: US scientists on Fauci leaving NIH role

Fauci #Fauci

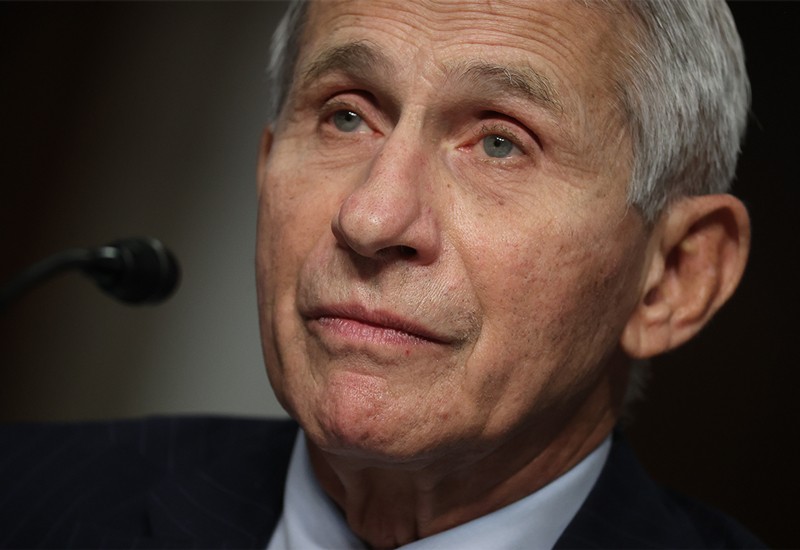

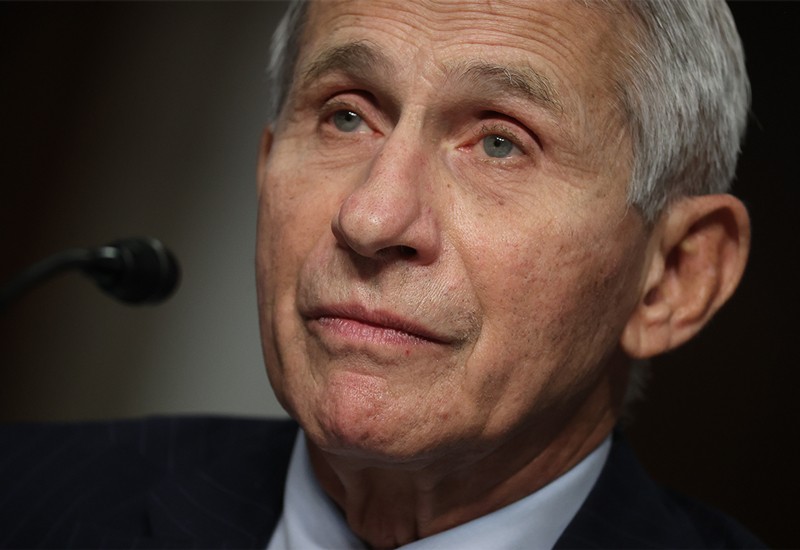

Chief US medical adviser Anthony Fauci has testified before Congress numerous times throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.Credit: Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Anthony Fauci, who has been the top infectious-diseases adviser in the United States for almost 40 years, announced on 22 August that he would resign from his leadership roles in December. Although many scientists are saddened to lose his guidance, they understand his desire to step down. No other federal scientist has held a top position for as long as Fauci has.

“Dr. Fauci is the most dedicated public servant I have ever known,” says former US National Institutes of Health (NIH) director Francis Collins, who has worked closely with Fauci over the years. “His contributions have saved countless lives from HIV/AIDS, Ebola and SARS-CoV-2, and will stand as profoundly significant gifts to humanity.”

US President Joe Biden, who elevated Fauci to be his top medical adviser, echoed Collins’s sentiments. “His commitment to the work is unwavering, and he does it with an unparalleled spirit, energy, and scientific integrity,” Biden said. As vice president, Biden worked with Fauci on the US response to outbreaks of the Zika and Ebola viruses.

Researchers that spoke to Nature say that Fauci will be best remembered for his unwavering dedication to research and the development of treatments for HIV, as well as for his uncanny ability to communicate directly and clearly to the public. Whenever there was a difficult public health emergency, “the government would trot out their best weapon — Tony Fauci”, says Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. She joked with colleagues that it was clear if a pathogen was worth worrying about based on the number of times Fauci appeared on television, nicknaming the phenomenon the ‘Tony Fauci index’.

‘Determined and aggressive’

Fauci has helmed the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland, under seven US presidents, starting with Ronald Reagan in 1984. Most recently, he became the face of the US response to the COVID-19 pandemic and a trusted voice worldwide that helped millions to make sense of a rapidly-evolving threat. During his tenure, he transformed NIAID from a lesser-known NIH institute with a US$350 million annual budget to a global role model in infectious-diseases research with a budget of over $6 billion.

Although Fauci is one of the most highly-cited scientists of all time for his work on HIV immunology and has been well-known in the infectious-diseases research community for decades, his role as a leading expert has at times been tumultuous. During the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and early 90s, activists felt that NIAID’s clinical trials were moving too slowly to help people with HIV gain access to life-saving therapies that were still in testing. They blamed him for unnecessary deaths, staging protests in front of his office. Fauci began a dialogue with the activists that within years led to effective treatments to suppress the virus that would become the global standard of care. This type of collaboration with the community was unprecedented and became a model for future health-care leaders, says Steven Deeks, an HIV clinician at the University of California, San Francisco. “But Tony was the first,” he says.

Working with former president George W. Bush, Fauci also helped to design the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a global programme launched in 2003 to provide treatment for people with HIV. PEPFAR, which is probably Fauci’s greatest and most impactful accomplishment, Deeks says, has “unequivocally saved millions of lives”. Bush awarded Fauci the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2008 for his “determined and aggressive efforts”.

In 2014, at a time when people worried whether the Ebola outbreak in West Africa would become a pandemic, Fauci notably hugged a nurse who had been infected with the virus and treated at the NIH — which Fauci later said he did to show his staff he wouldn’t ask them to do anything that he wouldn’t do himself. That “extraordinary level of empathy” will be difficult to replace, Nuzzo says.

Fast-forward to 2020, and Fauci once again came under fire — this time from the president whom he was serving. Dissatisfied with Fauci’s guidance to curb the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus’s spread by implementing interventions such as masking and social distancing, former president Donald Trump attempted to silence Fauci by, at times, preventing him from speaking publicly. Trump also hinted that he might fire him (Fauci is a civil servant in the US government, not a political appointee, so it is unclear how Trump might have done this). Fauci has received death threats and has had federal guards overseeing his safety.

“Because of the sustained attacks on him and failure of our political leaders to rebuke those attacks, his ability to communicate was lessened,” Nuzzo says.

The next generation

Although he did not detail his future plans, Fauci was clear when announcing his departure that he would not be retiring. “I plan to pursue the next phase of my career while I still have so much energy and passion for my field,” he wrote. He indicated that whatever he does next, it will involve advancing science and public health, and mentoring the next generation of science leaders.

Fauci’s mentorship has helped shape Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, to be the scientist she is today. Although Iwasaki says she was just a “lowly postdoc” at the NIH in 1998, Fauci took time out of his schedule to meet with her on several occasions. “He has this way of elevating scientists around him,” she says.

NIAID did not respond to an e-mail inquiring when Fauci’s replacement might be named. But Deeks hopes the new director will have the same desire to continue trying to end the HIV epidemic. “Tony has carried this on his shoulders for 40 years,” he says.