Elections Canada launches online disinformation tool to prepare voters for next federal election

Elections Canada #ElectionsCanada

Elections Canada is trying to insulate Canadian voters from false narratives and information during the next federal election by launching an online tool to help voters cut through misinformation and disinformation about the electoral process in Canada.

The ElectoFacts website, launched this week, provides factual information to debunk the most common misconceptions observed by Elections Canada officials in recent years.

“Building resilience against inaccurate information helps strengthen the overall health of democracy,” Chief Electoral Officer Stéphane Perrault said in a statement.

“ElectoFacts is one additional step electors can take to ensure they are informed and have accurate information about the electoral process.”

The ElectoFacts website says that it does not intend to establish Elections Canada as “the arbiter of truth” that will actively monitor the accuracy of statements and information distributed by parties and candidates. The agency said it will instead focus on providing correct information about elections that Canadians can easily access.

Visitors to ElectoFacts can scroll through eight categories where disinformation is taking place:

Each category displays the “inaccurate information observed” with an accompanying and detailed explanation of what is accurate.

Special ballots

On the subject of special ballots, or mail-in ballots, for example, Elections Canada said the two largest misconceptions were that 205,000 mail-in ballots were “lost, ignored” or deliberately not counted during the 2021 federal election.

The agency’s counter-information explains it issued more than one million special ballots in 2021 and 883,000, or 87 per cent of them, were returned on time and were counted.

Ballots that arrived late were not counted but have been preserved for a ten-year period, ElectoFacts website reads.

The special ballots information also explains the checks and balances that have been built into the voting system to ensure that people do not vote by mail and then vote again in person.

Other examples of misinformation and disinformation include whether votes can be bought by bribing Canadians, whether non-citizens can vote, whether ballot machines are used to count votes and whether Elections Canada rigs the vote.

Workers prepare the bins with names of candidates into which special ballots from national, international, Canadian Forces and incarcerated electors will be counted and organized, at Elections Canada’s distribution centre in Ottawa on election night of the 44th Canadian general election, on Monday, Sept. 20, 2021.

Workers prepare the bins with names of candidates into which special ballots from national, international, Canadian Forces and incarcerated electors will be counted and organized, at Elections Canada’s distribution centre in Ottawa on election night of the 44th Canadian general election, on Sept. 20, 2021. (Justin Tang/The Canadian Press)

The Canadian Election Misinformation Project, co-managed by McGill University and the University of Toronto, also looked at the issue of misinformation and disinformation during the 2021 election.

Their report found that while there was “widespread” misinformation and disinformation, its overall impact on the results of the election were minimal.

The report said messages claiming that Canadians who were not fully vaccinated would be unable to vote were widely circulated on social media.

The report also found false messages were being spread on social media claiming that candidates were being removed from ballots and that machines counted all the votes cast, when in fact all votes are counted by hand.

2016 U.S. election disinfo raised alarm bells

Aengus Bridgman, director of the Canadian Election Misinformation Project, told CBC News the 2016 election in the United States, which saw an aggressive and unprecedented Russian disinformation campaign, raised alarm bells in the West over the threat to democracy.

“If our election results are later shown to have been the result of a disinformation campaign that was decisive in an election, it would cause an enormous diplomatic and constitutional crisis,” he said.

Bridgman said it is important to get the right information out there, proactively, where people can access it before the election disinformation begins to spread, because once false information has spread and gained traction, it is much harder to counter.

He said his research has shown that Elections Canada is one of Canada’s most trusted institutions, and so having that information hosted on its website will help establish what is, and is not, factual.

“There’s pretty good evidence that this type of thing should be effective,” he said.

Bridgman said Canadians can also help to fight disinformation in their everyday lives by resisting the temptation to cut family, friends and neighbours off and push them out of their lives if they start espousing views based on disinformation.

“Keeping lines of conversation open is incredibly important,” he said. “One of the things that can happen is that people can join [disinformation] communities and drive their real physical committees away, and then they become isolated and … that becomes very dangerous.”

Make election disinformation illegal, chief electoral officer says

After the 2021 federal election, Perrault published a report that called for a crackdown on hate groups, improved regulation of third parties and new laws to make it illegal to spread disinformation about elections and voting.

The report’s recommendations were based on an analysis of what took place in both the 2019 and 2021 federal elections in Canada.

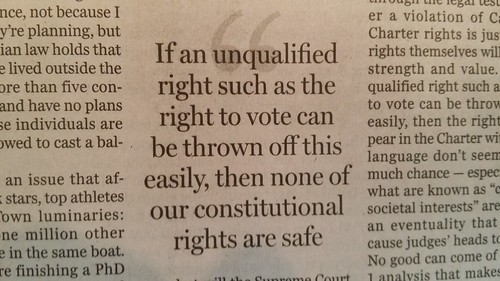

Perhaps most significantly, Perrault’s report called for legislative changes to make it illegal to spread information that disrupts an election or undermines its legitimacy.

The report said that action must be taken because the continued spread of disinformation could “jeopardize trust in the entire electoral system on which democracies rest.”

Perrault said there are laws on the books to deal with disinformation that were used when misleading robocalls were made to voters in Guelph, Ont., during the 2011 federal election.

“But there’s nothing right now in the legislation where there is a deliberate campaign to undermine the process or undermine confidence in the result,” he said in 2022. “This complements a number of existing provisions.”