ECHR explained: What does the agreement say and why it’s difficult for Britain to leave

ECHR #ECHR

Conservative calls to quit the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) to tackle the Channel asylum crisis were reignited this week after Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick suggested the Government was prepared to do “whatever is necessary” to stop small boat crossings.

What is the ECHR?

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is an international treaty which came into force in 1953 that broadly protects the human rights and political freedoms of all citizens within the 46 states belonging to the Council of Europe.

These include the right to life, freedom from torture, freedom from slavery, freedom of expression, assembly and thought, the right to a family life and so on.

The ECHR is not a European Union convention so the UK’s adherence to its principles were not affected by Brexit.

The convention is ruled on by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, with binding judgments although some nations have in the past ignored these.

Why is the ECHR in the news again?

There have been repeated calls from within the Conservative Party for the UK to leave the ECHR after an interim order from Strasbourg frustrated the Government’s first attempt to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda last year.

Mr Jenrick on Wednesday once again raised the prospect of leaving amid the Government’s so-called “small boats week” of announcements to crack down on the Channel crisis.

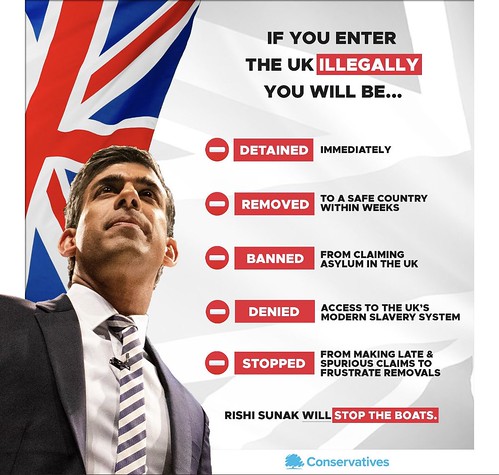

The Government insists it can deliver on Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s pledge to “stop the boats” within the convention but Mr Jenrick’s comments once again sparked a live debate to quit the agreement as a plan B.

The Government has already taken powers in the Illegal Migration Act to ignore the kind of interim injunction that grounded the Rwanda deportation flight last year, but these have not yet been tested as the domestic Supreme Court is yet to rule on the plan.

What are the views on the ECHR within the broader Conservative Party?

There are some Conservative MPs who are strongly opposed to the UK remaining in the ECHR as a matter of principle.

This is because the convention protects the rights of everyone within Council of Europe states, regardless of which country they are a citizen of.

Therefore the ECHR is seen by some Tories, most notably Home Secretary Suella Braverman, as an unreasonable restriction which limits domestic action on not only migration but other politically sensitive issues such as security and criminality.

Others in the party, such as Foreign Secretary James Cleverly, argue it is in the UK’s interests to remain a signatory to the convention to maintain global influence and reputation.

What are the implications for the UK of leaving the ECHR?

For the UK to leave the ECHR, the Human Rights Act 1998 would have to be repealed.

Various other legislation which refers to the Act, including statutes relating to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, would also have to be amended.

There is also the complex matter of a potential violation of internal law relating to the UK’s agreement to be part of the ECHR in signing a number of treaties.

For example, the Good Friday Agreement requires the ECHR to be part of law in Northern Ireland.

Therefore, the UK departure from the convention would be a breach of the Good Friday Agreement, which would still be the case if a new domestic Bill of Rights replaced it.

Furthermore, the overarching Brexit trade deal contains an obligation for both the UK and the EU to continue their commitment to human rights.

However, the removal of the ECHR would not automatically lead to a suspension or termination of the agreement.

As well as the practicalities, there are warnings that leaving the convention could damage the UK’s reputation as it would be left in the company of only Russia and Belarus as countries which have left the ECHR.

The two nations were expelled following the invasion of Ukraine, meaning quitting the bloc could also affect the strength of the international response to the war.

Leaving would also make it difficult for the UK to urge non-European states to operate in line with an international rules-based order, a longstanding foreign policy priority.