Console: The inside story of a con that shook the nation

Paul Kelly #PaulKelly

In court today, Patricia Kelly, the wife of the founder of Console, Paul Kelly, was fined for actions relating to her role in the charity.

It ended a chain of events that began with an RTÉ Investigates broadcast in 2016. This is the inside story of that investigation and the activities of what was then one of Ireland’s most prominent charities.

Tommy Morris called the Prime Time office in 2012. He had some information about the head of Ireland’s leading suicide bereavement charity, Console.

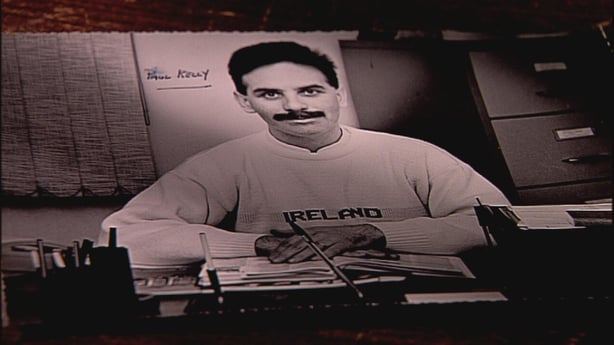

Paul Kelly, the co-founder of Console, had grown up in the same neighbourhood as Mr Morris, in Dublin’s Ballyfermot.

At the time of the phone call, the Console charity was in receipt of hundreds of thousands of euro in funding annually from the State, mainly delivered in the form of grants from the Health Service Executive.

Mr Kelly had long said publicly that he set up the charity to honour a sister who died by suicide, to provide quality counselling services to families equally bereaved.

He was awarded the prestigious People of the Year Award in 2014, and Console attracted celebrity figures as supporters. RTÉ’s Miriam O’Callaghan and Ray D’Arcy, as well as the late Keelin Shanley, were among those who gave their time free of charge at Console events.

President Mary McAleese was a patron of Console, so was her successor, Michael D Higgins.

But Tommy Morris knew that Paul Kelly had a long history as a scammer. In his phone call to Prime Time, he gave information about Mr Kelly’s past and alleged wrongdoings. The information was believable, but not verifiable to the standards that our defamation laws require.

But, like all investigations, one thing led to another. Mr Morris told Prime Time that back in 1990, RTÉ had broadcast a lengthy report for a consumer show about another charity founded by Paul Kelly, long before Console.

That programme, called ‘Look Here’, was a relatively short-lived series, lasting only two seasons. The report about Paul Kelly was in the first programme of the first season and the reporter on the show was Mairead McGuinness, now a European Commissioner.

Shay Howell was the researcher on the programme. By 2012, Mr Howell no longer worked in RTÉ, but he had kept reams of documents relating to the programme in his attic.

Most of the documents had been delivered anonymously in boxes to RTÉ’s TV reception days before the broadcast. They turned out to be a journalist’s treasure trove.

Former RTÉ researcher, Shay Howell

Former RTÉ researcher, Shay Howell

In the boxes was a newspaper clipping about a case where Paul Kelly had pretended to be a doctor and got a job at the Royal City of Dublin Hospital in Upper Baggot St. It detailed how he had used the medical registration number of a doctor with the same name, and even opened a bank account in the name of Dr Paul Kelly. He worked at Baggot Street hospital for around three weeks as a doctor until gardaí were alerted.

He subsequently admitted to the fraud in Dublin District Court on 17 June 1983 and was given the benefit of the Probation Act.

No longer claiming to be a doctor, by 1986, Paul Kelly was claiming to be a counsellor and he set up Christian Development Services which counselled people for problems ranging from marriage difficulties to sexual abuse.

Like most of those who did counselling work for Christian Development Services, Mr Kelly had no professional qualifications. He did, however run a very professional fundraising operation.

There was a “Bible for contacts,” said Mr Howell, containing “the names of one thousand companies and the estimated donations that each company would be expected to give.”

Some donations came from philanthropists and companies like a then little-known bank called Anglo Irish Bank, which, for example, gave £200 in one donation. Carrol Tobacco gave £250 in another, EBS gave £500, Digital Equipment International gave £1,000. Ryanair donated two free return tickets to London. One philanthropist gave £5,000.

Part of Paul Kelly’s success was that he falsely claimed that well-known people were on the board of Christian Development Services. These included co-founder of the Central Remedial Clinic, Lady Valerie Goulding, and then-Minister for Labour, Bertie Ahern.

Mr Ahern told RTÉ’s Look Here programme in 1990 that the charity had claimed him as a trustee after he “attended a meeting that they held” in 1988.

Archive image of Paul Kelly

Archive image of Paul Kelly

“For several months a number of business people were continually ringing my office,” he said, “saying they believed I was a trustee, saying people were ringing to collect donations and they were using my name as a person closely involved [with the charity].”

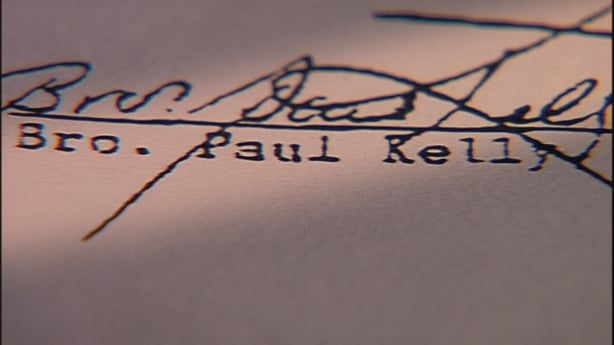

The documents also showed that Paul Kelly raised money under false pretenses. He sought donations while dressed as a priest and signed letters seeking funds as Fr Paul Kelly, Fr John McCarthy, Fr John McKenna OSD and Brother Paul Kelly SP.

The OSD acronym he used referred to ‘Order of San Damiano’ while SP stood for ‘Servants of the Poor.’

Both orders were based at a house Mr Kelly rented in Clondalkin. Despite the plurality implied by “Servants of the Poor” Paul Kelly was the only member of this order. Likewise for the Order of San Damiano. Both orders existed only in Paul Kelly’s head.

“He actually had a Dominican robe,” former RTÉ researcher Mr Howell recalled. “And he wore that when he was going around looking for money. The main modus operandi was to collect money, purporting to be for charities. But, in fact, it was for himself, basically for his own lifestyle,” Mr Howell said.

“It was like a rehearsal, if you like, for his later activities in Console.”

Suspicions by staff at Christian Development Services that Paul Kelly was embezzling money from the charity were strengthened when, despite presenting himself as an unpaid volunteer, he took a two-month holiday in Australia.

He wrote a postcard to staff at the charity telling them that he was “enjoying every moment of my stay” and that he had “travelled extensively throughout Western Australia.”

In another postcard, he wrote about “having a wonderful time.” He signed both postcards as ‘Paul.’ Upon his return in May 1989, he wrote a letter to one of his main donors, thanking her for her “generous support, help and assistance throughout our financial crisis.”

He began the letter by falsely claiming that he had recently returned from Australia “having spent a period of two months developing an assessment programme for a series of crisis centres in Perth and Sydney.” He signed that letter as ‘Rev Paul Kelly OSD.’

A document in which Paul Kelly refers to himself as ‘Brother’

A document in which Paul Kelly refers to himself as ‘Brother’

Paul Kelly had made one significant mistake in this time, however. While Christian Development Services did not have Bertie Ahern on its board of directors it did have real directors, who worked for CDS.

In December 1989, some of them convened a meeting and forced Paul Kelly to resign as an employee and as a director, alleging that he had “misappropriated funds” of the charity.

Mr Kelly denied this accusation.

Paul Kelly learned a valuable lesson from his ejection. When he founded Console 13 years later, he never had a proper, independent board of directors.

Soon after CDS, Paul Kelly set up a short-lived charity called Community Care. He continued to masquerade as a priest, and used different priestly or brotherly names. But he remained a successful fundraiser, using religious phrasing to show appreciation.

In one letter thanking a company who had donated £500 to Community Care, he wrote “…may the Lord grant you the graces and blessings you so richly deserve.”

In 1990, £500 was 30% above the average industrial weekly wage.

The ‘Look Here’ programme researched by Shay Howell was broadcast that year, but by that point it appeared Paul Kelly was in Australia.

With little follow-up from newspapers, and no online search engines yet operating, the details were quickly lost from the collective memory.

Come 1993 and Paul Kelly had returned to Ireland, using the name Seamus O’Ceallaigh (the Irish-language version of his father’s name), he was involved in an alleged scam involving door-to-door hawking of pictures which he allegedly duped businesses into purchasing.

In 2002, he set-up Console, and over the following decade grew it into one of the most prominent charities in the country.

Tommy Morris’s call to Prime Time led us to Shay Howell’s boxes of documents. They painted a damning picture of Paul Kelly’s past behaviour, but also raised the question: had the leopard changed his spots? Was there proof that Paul Kelly was still scamming people and was Console his vehicle?

By then, Paul Kelly was no longer publicly engaging in blatant fraudulent fundraising by pretending to be a priest or using multiple aliases.

Getting evidence that he was still a conman would be a challenge that – hindered by various legal and editorial concerns, research cul de sacs, mixed results from multiple freedom of information requests, and the demands of other projects – took four years.

Gradually, however, repeated FOI requests over years yielded documentary evidence that Paul Kelly altered audited accounts to hide the fact that he had been paid over €200,000 in director’s fees. Payments to directors are not allowed under the law.

Accounts sent to State funders were also changed to mask the fact that his wife, Patricia, was on the board of Console. In accounts submitted to the Companies Registration Office, she signed her name as Patricia Kelly. But in accounts to State agencies seeking grants, she used her maiden name, Dowling, masking any connection to her husband.

Under the rules of the Revenue Commissioners, which gives tax-free status to charity income, charities should not have connected people, such as family members, on their board.

Having a board made up of related people is a red flag for a charity’s governance.

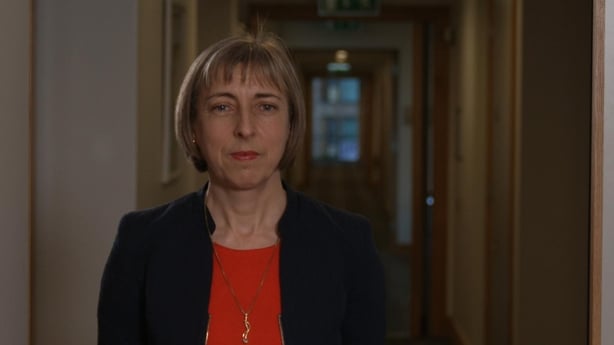

“That means there’s no independent voice in that charity,” Professor Oonagh Breen of UCD’s Sutherland School of Law, told Prime Time.

“There’s perhaps a greater temptation to think of your own interest and not have that constructive irritant, that other person on the board who says, ‘is this okay? And should we be doing that?’”

Financial records also included different dates of birth for Mr Kelly and his wife Patricia, registered for different companies.

Professor Oonagh Breen of UCD

Professor Oonagh Breen of UCD

Console accounts obtained from funding agencies under FOI, and from the Companies Registration Office, showed that there were six different sets for 2012 accounts for the Console, all apparently prepared by the board (Paul and Patricia Kelly) on the same day.

Forensic accountant Jim Luby told RTÉ Investigates in 2016 that in his three decades of professional experience he had “…seen lots of things, I can’t ever say I have seen six sets of accounts for the same year, with such variations.”

Former Console counsellor Jean Casey shared her concerns with RTÉ about poor governance of the organisation. And when we informed former Senator Jillian van Turnhout that Console had falsely claimed her as board member along with five others in a funding application to the HSE, said she was “stunned”.

“I have never been a member of the board of Console… the height of my interaction has been to tweet their helpline number,” she said.

In its financial accounts, including those sent as part of grant applications to agencies like the HSE, Department of Health and the Family Support Agency (now part of Tusla), Console often included another name as director, Joan McKenna or Joan Burke McKenna.

Paul Kelly has a sister called Joan McKenna (the name Joan Burke McKenna was a fiction), but she was unaware that she was on the board. Ms McKenna was not involved in Console and did not derive any financial benefit from it.

Mr Kelly registered her using his home address, not hers. He signed her name on company documents, sometimes clumsily.

In a funding application to State agency Pobal in 2014, he signed a “P” before switching to “Joan”, resulting in the signature “P Joan McKenna.”

By June 2016, RTÉ Investigates had enough evidence to broadcast, including some hugely significant details from a HSE audit that revealed that charity money had been spent on travel by Paul Kelly to Hong Kong, New Zealand and Australia as well as lavish spending by he and his wife using charity credit cards on designer clothing and restaurants.

Mayo woman Anne Lynch watched the programme in “shock and… disbelief,” she said.

After selling a thriving restaurant she ran with her husband during the Celtic Tiger period, she retrained as a psychotherapist and became an enthusiastic believer in Console’s mission. She donated a cottage in her native Swinford for use by the charity as a counselling centre, and later worked as the charity’s Suicide Bereavement Liaison Officer for Sligo and Leitrim.

“I was sitting by my fireside with my husband – married to him for 48 years, an absolute gentleman – he looked at me, and I thought, ‘this is the worst thing that could have happened’, because as it was like, I felt he thought I had deceived him, but I knew nothing about it.”

After the RTÉ broadcast, Console went into freefall. David Hall, who has a long history of involvement in charities such as the Make-a-Wish Foundation and the Irish Mortgage Holders Organisation, was appointed as an emergency CEO for Console.

Console’s solicitor had phoned him on the day of the Prime Time broadcast to say: “‘Prime Time are going to run a programme, the charity is going to need some help.’”

“Staff were devastated, donors were devastated, donors affected by suicide – devastated, people receiving counselling that day by staff – devastated,” Mr Hall said.

David Hall

David Hall

The charity went into liquidation three weeks later. Subsequent examinations showed that its financial controls were virtually non-existent. Massive, but ultimately untellable amounts of donations from the public, had been spent by the Kellys on personal items.

An analysis by the liquidator of credit card spending, seen by Prime Time, shows that over a 12-year period, €27,306 was spent on clothes, including designer labels. Some €39,385 went on groceries, €57,447 on restaurants, and €69,230 on hotels.

Over €213,000 was taken out in cash withdrawals on cards held by Paul and Patricia Kelly.

Little or no documentation existed as to the reasons for the withdrawals.

One statement for a credit card in Patricia Kelly’s name shows that within the space of four days in September 2012, transactions included €79 at Marks and Spencer, €96 at a pub, €223 at Ralph Lauren, and €590 booking a room at the Marina Bay Sands Hotel in Singapore.

The audit showed that charity money was used to pay for travel to Sydney, Barcelona and Dubai, a stay at a five-star Hong Kong hotel for Paul Kelly, admission to Singapore Zoo, shopping visits to the men’s suits specialists, Moss Brothers in London. As well as restaurants and supermarkets near the Kelly home in Clane. And, for Patricia Kelly’s use, a €57,000 Audi.

Much of the charity’s income was in the form of cash donations. While Console branches kept records of cash donations, HSE auditors noted that Console’s headquarters in Kildare did not. There, Paul Kelly was in charge of handling donations, and opening the post.

Based on conversations he had with donors, David Hall estimates that aside from the lavish credit card spending on clothes, food and travel, that “in excess of €700,000 in cash” disappeared from Console, pocketed, he believes, by Paul Kelly.

“There was a cycling event not too far from the time of Console’s collapse,” he told Prime Time.

“€70,000 was raised, I could only find €8,000 in the accounts. Where is the rest gone? Those people who cycled half-way round the country to raise money for a cause they believed in, many of whom had been affected by the intentions and purposes of charity – and yet, that cash never materialised. Money’s gone. 100%, money’s gone.”

Paul Kelly took his own life as he was facing imminent criminal charges relating to his theft from the charity he founded.

Console was one of Ireland’s most prominent charities

Console was one of Ireland’s most prominent charities

His wife, Patricia Kelly, was in court on Thursday, having pleaded guilty to ‘failing to keep proper books of account other than willfully.’ She was fined €1,500.

She had faced 28 charges, including 25 under the Theft and Fraud Offences Act, but a trial was avoided through her guilty plea.

Patricia Kelly did not respond to a written request for an interview and as she left court, she did not respond to several questions put to her by Prime Time.

“It’s a very serious offence,” said charity expert UCD’s Professor Oonagh Breen.

“You must keep proper receipts. You must be able to explain where your sources of income came from and what you spent that money on. You must be able to show the chain of custody for that money through your accounts.”

The dominant force in the charity was not Patricia Kelly but her husband.

Patricia Kelly seen leaving court in 2016 (Pic: RollingNews.ie)

Patricia Kelly seen leaving court in 2016 (Pic: RollingNews.ie)

“Paul Kelly was completely in control,” said David Hall. He was “an individual who defrauded the organisation, controlled the organisation.”

He was not a man that many people involved in the charity got to know well. Anne Lynch remembers him as someone who seemed too busy to engage in deep conversation.

“Always on the phone,” she said, “never had time. But I thought, well, of course you’re busy if you’re such a fantastic organisation, you have so much going on.”

When another counsellor who worked with Console, Jean Casey, spoke to Prime Time she used the phrase “smoke and mirrors” to describe how the organisation was run.

Tommy Morris, whose original phone call to Prime Time sparked our investigation, says “I was always suspicious of him. I always felt that he wasn’t genuine.”

There are even questions about the basis for Paul Kelly setting up Console.

Tommy Morris

Tommy Morris

On 19 October 1995, Paul Kelly’s youngest sister Sharon died a grim death by suicide in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. She was found by a member of the public face down in the grass after overdosing on alcohol and drugs. She had written suicide notes.

At future Console events, Mr Kelly consistently cited her death as his inspiration for setting up the charity, but details he gave about his sister were incorrect.

Though Sharon Kelly died in 1995, Paul Kelly repeatedly stated that she died in 2001, the year before Console was founded, or even later, apparently to support his case that her death was the reason for founding Console.

He said she was a 21-year-old high achiever in college. In fact, she was 23 when she died and had left school before her Leaving Cert. Paul Kelly stated repeatedly if his sister “had been suffering from mental illness or chronic depression or had a trauma” in her life “we could have coped better.”

But, as Paul Kelly told gardaí after his sister was found dead, she had previously attempted suicide and had a long history of depression.

Two months prior to her death she was admitted to a psychiatric facility after attempting suicide, according to inquest documents.

Paul Kelly also repeatedly suggested that Console was his first involvement in a charity, and that his background was “in business.” That too was a lie.

Paul Kelly presented Console as “a new cause” said David Hall, “forgetting he had set up previous [similar] organisations.”

“It was sold based on personal family experience…” he added, “and that, to most people, would be reprehensible of a person to utilise such a genuine tragedy for such personal, devious, means.”

The Charities Regulator was only two years old at the time of the Console scandal and was largely a toothless bystander. After the Console scandal emerged, it gained extra powers under the Charities Act, with the commencement of ‘Part Four.’

“Part Four has three really important sections,” says Professor Oonagh Breen.

“It enables statutory investigations to be undertaken. It enables the charities regulator to apply intermediate sanctions, and it also enables the charities regulator to go to the High Court to seek protection of charity assets. That all requires resourcing. And after Console, the resources were found to give the regulator the necessary funds to commence those sections.”

However, concerns remain about governance in parts of the charity sector in Ireland, and further legislation to improve the regulation of charities is currently being deliberated on in the Oireachtas.

There is no guarantee however that it will pass in the lifetime of the current Dáil.

“We have waited a long, long time for this amendment bill to come about. Draft regulations started back in 2016. That is eight years ago,” said Professor Breen.

“Charity law, unfortunately, is not something that ever demands the Dáil time that it actually deserves. We have to wait… until we get a scandal. And when there’s a scandal, all of a sudden our flaws, the deficits in our regulation are held up, uh, to public scrutiny. And there is hue and cry for things to be better. But we shouldn’t wait for those mistakes to occur.”