Cabinet, board knew about Eskom corruption – and did nothing

Cabinet #Cabinet

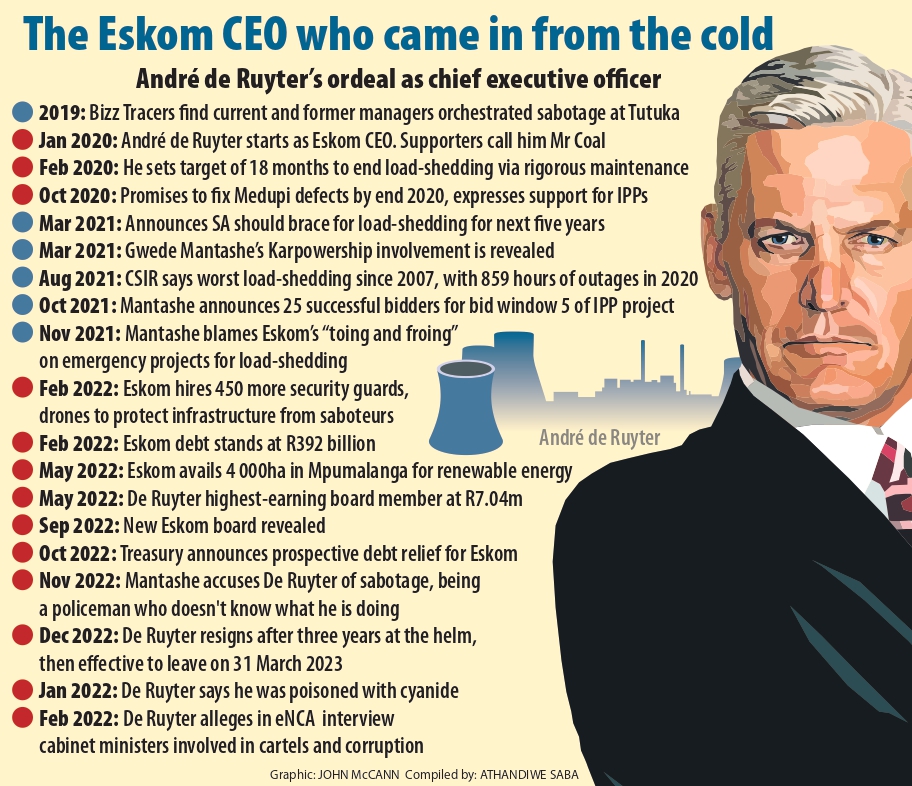

The corruption bombshell dropped by Eskom’s former chief executive, André de Ruyter, has been an open secret in the corridors of the power utility and the government for months.

Several high-ranking sources in Eskom and government have told the Mail & Guardian that everyone from the board of Eskom to ministers Pravin Gordhan, Gwede Mantashe and even President Cyril Ramaphosa were aware of not only the allegations but also the findings of investigations into the rampant corruption at Eskom.

The new Eskom board, announced in September, was also made aware of the damning allegations and a source internally said its “hands were tied” because of political pressure.

The source added that when the new board was elected, its members were well aware of cartels operating in Eskom because they are a “known secret within the management of the utility”.

“De Ruyter just blew the lid open. This cartel business has been in the utility way before he joined, even during the times of the former CEOs,” the source said.

Another Eskom source said the revelations had sparked “damage control”.

“This does not bode well for the ruling party, so what is currently happening is we are trying to close all gaps that will appear. People are being bought to be silent about this matter,” they said.

“Eskom can’t afford any bad publicity but everyone knew about this. That is why it was difficult to support De Ruyter in his quest to clean up the corruption. Everyone toes the line. De Ruyter stepped out of line and that is why he was alienated and that is why the likes of Rhulani Mathebula also left.”

A board member, who asked not to be named, said: “Everyone is running around like madmen. It is a mess, and threats are following, people are planning to jump ship because they are implicated somehow. Many are planning to leave the country for the safety of their families, it’s a mess.”

Last week several publications reported that De Ruyter had sourced private investigators to track the cartels that have brought the power utility to its knees. These investigators were paid by private funders, it is understood.

They revealed a vast network and several cabinet members are allegedly involved and driving the syndicates.

In his interview with eNCA, De Ruyter declined to name the senior ANC politicians involved in — and leading — the syndicates.

He said he had “expressed my concern” to a senior government minister about what he saw as attempts to “water down governance” in the more than $8.5 billion in climate change funding.

“The response was essentially, ‘You know, you have to be pragmatic, you have to, in order to pursue the greater good you have to enable some people to eat a little bit’,” De Ruyter said.

He said he had pointed out to a cabinet minister — since revealed to be Gordhan — that syndicates at Eskom were linked to a cabinet minister and a high-level politician. De Ruyter did not name those involved, citing libel concerns.

A former board member said they were aware that more than two cabinet members were implicated.

“There is one that is being forgotten, and this minister keeps escaping in situations, because the member is a mafia and owns the Mpumalanga province,” the former board member said.

“Even without cabinet powers the members will still succeed in this business because they have something on everyone,” another former board member said.

Gordhan was not the only cabinet member who was aware of the syndicates and corruption in Eskom.

A former high-ranking Eskom leader said Ramaphosa had knowledge of the corruption at Eskom from first-hand interaction with its executives and managers. They said De Ruyter had also informed Gordhan on several occasions of the corruption that involved politicians.

The source recounts how, during one of Gordhan’s oversight visits to Tutuka last year, Ramaphosa, together with Police Minister Bheki Cele, Gordhan and Mantashe, were told of the extent of criminality at the power station by Eskom executives and the station’s managers.

The Tutuka station manager showed Ramaphosa that they had to wear a bulletproof vest for fear of being shot.

During the visit, Rampahosa said the government team had been well briefed on the work and problems at the power station. He added that corruption and fraud were pervasive at Tutuka. “Theft and fraud makes it very challenging for the power station to operate optimally. That is being attended to now where

corruption is being dealt with and people are getting arrested as a result of the action that is being taken by management,” Ramaphosa said.

By the time of publication, Gordhan, Mantashe and the Eskom board’s spokespeople had not responded to questions regarding their knowledge and failure to report or further investigate what they were told close to a year ago.

Instead, in response to questions during a post-cabinet briefing on Thursday on whether Gordhan had reported what De Ruyter told him to the police, Minister in the Presidency Mondli Gungubele said this “doesn’t change the fact” that De Ruyter had a responsibility to report criminal activity to the police.

“We will leave that matter there. We take serious[ly] what this CEO has raised, but we also argue that a CEO can do better. A CEO is put in a position of power, and power to deal with that information unlike an ordinary citizen,” Gungubele told journalists.

He said the cabinet believed De Ruyter should “go further and give us more information” and ensure that law enforcement agencies followed up on what he had disclosed.

Ramaphosa taking a tour of Tutuka power station

Ramaphosa taking a tour of Tutuka power station

“We request that we leave this matter there. Dealing with individual ministers is neither here nor there,” Gungubele said.

He said names had been mentioned in public in connection with the matter, allegations had been levelled against a number of ministers in the past — himself included — with no proof being proffered.

“There are institutions to take care of these things. We take very serious[ly] what De Ruyter said, taking into account the position he held.”

He said De Ruyter’s allegations showed that he was concerned about the situation, which was something cabinet supported.

But two Eskom sources said De Ruyter brought law enforcement officials to Eskom’s Megawatt Park headquarters and showed them the growing evidence of cartels and corruption at the utility.

“They were shocked and angry. But nothing has come of it,” said one senior source.

Another source in the department of public enterprises also confirmed that several high-ranking politicians knew of the situation but said that De Ruyter “should have done more from the get-go”.

Presidential spokesman Vincent Magwenya said Ramaphosa had publicly acknowledged “many, many times” that there was corruption at Eskom.

“As the Presidency, we have communicated on progress being made in dealing with criminal syndicates operating in and around Eskom. And yes, when the President visited Tutuka power station and when he met with power station managers, he was briefed about criminal syndicates stealing diesel, diluting coal, stealing spares and equipment and sabotaging critical machinery.

“Government has deployed a multidisciplinary task team to Eskom that is made up of key elements of the security cluster, including SARS, SSA and the ID. There’s a dedicated Natjoints that sits regularly to monitor progress and allocates resources to respond to corruption and criminal cases at Eskom.

Magwenya added that Ramaphosa was not given the names of those allegedly involved in graft.

“No one has ever given the President any name of either a politician or syndicate leader that’s involved at Eskom. Andre publicly made a claim about a politician, and rightly so the president has said he must present that information to law enforcement agencies and must open a case against any individual he has information or evidence against.”

There has been some debate about whether a duty to report knowledge or suspicion of corruption involving more than R100 000 in terms of section 34 of the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act applies to political principles, including premiers and cabinet ministers, but a senior advocate who specialises in corruption matters said the correct view was that it does.

The public enterprises senior official and the former Eskom leaders also told the M&G that De Ruyter and Gordhan’s relationship had soured over the past two years because the former chief executive had been sidelined by the minister amid demands that power stations be run at maximum capacity.

De Ruyter began “snooping” into the syndicates a few months after he was appointed. According to the sources, the former chief executive informed the now suspended director general of the department, Kgathatso Tlhakudi, about the extent of the corruption in about May 2020.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The source said De Ruyter had told Tlhakudi the programme to arrest load-shedding announced by the president when he had cut short his trip to Egypt in December 2019 was “going in the wrong direction”, in part because of the high level of corruption and theft.

De Ruyter had been “exasperated” by the situation and the fact that the theft “had a strong political element to it” and had been advised to beef up security and bring in investigators to come up with a plan to deal with the corruption and theft.

De Ruyter is also understood to have briefed Tlhakudi again in 2021 about a report on theft at Tutuka, including that of cable from inside the facility. The report was then given to the department.

In 2019, a company called Bizz Tracers was mandated by Eskom, at power station level, to investigate the repeated breakdowns at Tutuka.

The report found that a current Tutuka manager allegedly orchestrated sabotage at the plant so that companies close to him would get contracts from Eskom.

The report says current and former managers allegedly stole cables and destroyed other components to receive repeat business and contracts at Tutuka. There has been no progress after a case was opened by the investigators.

The source said De Ruyter had interacted more regularly with Gordhan than with Tlhakudi. Gordhan also interacted directly with other top Eskom executives, bypassing the then chief executive officer.

But this was not the only frustration Gordhan posed. He allegedly also scuppered plans to boost the department’s anti-corruption capacity and to create a database to track the implementation of findings of the forensic reports commissioned at Eskom.

“The plan was that we would create a database so we could consolidate the findings and recommendations from the reports. This would allow us to track what progress had been made with each and would assist us with our reporting to parliament,” the source said.

The initiative was “killed”.

“The department and the minister really have a lot to answer to South Africans. For four to five years they have made a lot of noise, but what has come of all those forensic reports? What happened to them? Who has been keeping track of all of those, to ensure that they are in reality addressed?” the source said.

This was confirmed by the former senior Eskom official who said Gordhan interfered and undermined De Ruyter.

“Whatever you do, he wants to take it and own it. The energy recovery plan, which is now the president’s plan, was De Ruyter’s plan with the board. We brought in five experts, economists, electrical engineers from the country and abroad and produced a plan,” they said.

“Because we had done that and excluded him, he went to the president and the president said he wanted to consolidate it. They just polished it with politics. Essentially it was Eskom’s plan and it was essentially the plan that De Ruyter had talked about in 2020; it’s just that Mantashe and Gordhan did not want it.

“The plan that they will now implement is the plan that will leave as a legacy for Eskom and it’s André’s plan,” the source added.

The Eskom source said Gordhan was part of the problem at the utility and that the current board had communicated to them the difficulties in dealing with the shareholder.

They said there was some opposition to an investigation by De Ruyter into the dealings of the ANC’s investment arm, Chancellor House, with the Medupi and Kusile power stations.

In 2006 the M&G broke the story that Chancellor House had targeted investments in sectors of the economy where government institutions dished out opportunities such as business rights or contracts.

A follow-up story in 2007 showed that a contract to supply steam generators for South Africa’s first new major power station in two decades had been awarded to a consortium led by Hitachi and included the ANC’s investment arm. About 60% of the contract was to be performed by local subsidiary Hitachi Power Africa, which is 25% owned by Chancellor House. The ANC company then had a R3 billion stake in the contract.

Recent News24 reports showed how the ANC benefited from R38 billion tenders awarded by Eskom to Hitachi Power Africa for the construction of boilers at Medupi and Kusile.