Buffalo shooting: How far-right killers are radicalised online

Buffalo #Buffalo

By Shayan SardarizadehBBC Monitoring

Image source, Getty Images

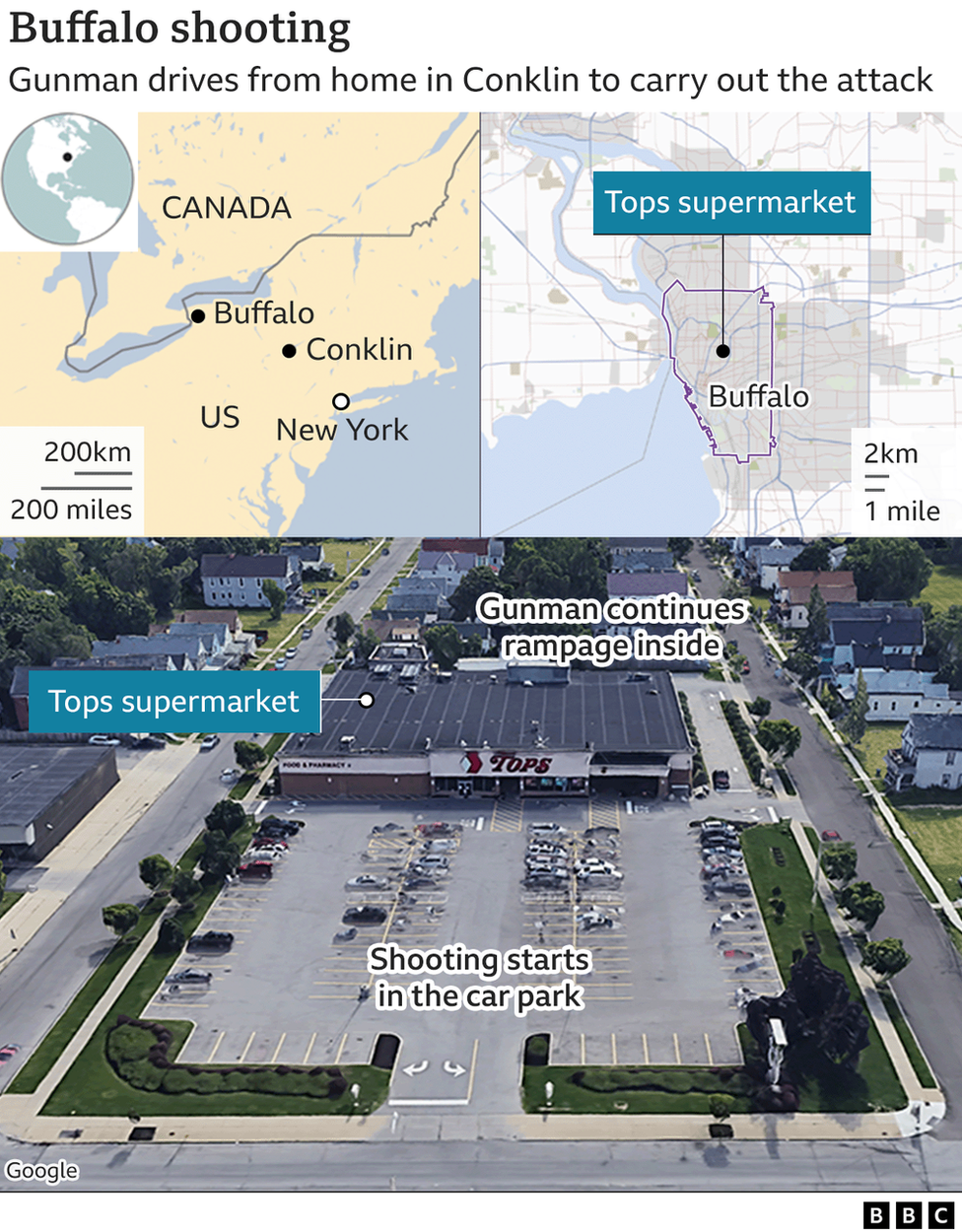

The racially motivated attack that left 10 people dead at a New York state supermarket is just the latest example of violence inspired by online extremism.

The shooting spree in Buffalo followed the exact blueprint of similar attacks around the US and the world.

It’s also happened in Pittsburgh, Christchurch, Poway, El Paso and Halle – internet-radicalised racist white men deliberately targeting members of a specific community, leaving extensive trails chronicling their extreme views online.

How did the perpetrators get immersed in extremist online subcultures? And what can be done to tackle the violence that springs from these groups?

Radicalised online

Like others before him, Payton Gendron, 18, the main suspect behind the Buffalo attack, posted a lengthy so-called “manifesto” explaining his motives and beliefs.

Some of the text is copied and pasted from similar racist manifestos written by 2019 Christchurch mass murderer Brenton Tarrant and other violent assailants. Gendron cites Tarrant as his main inspiration and gateway into the world of online extremism and white supremacy.

All of the recent far-right assailants cite the internet as the starting place for their journeys towards radicalisation. Their manifestos and writings show they were well-versed in the online subcultures, conspiracy theories and memes, and used those to deliberately “troll” or misinform.

Notably, all of them are committed anti-Semites and Holocaust deniers, and cite a wide range of conspiracy theories.

Nearly all of them reference “white genocide” and “white replacement” conspiracy theories, as well as their resentment of immigrants and minority groups, as the bedrock of their belief system and the main motivation for their violence.

“The idea of a ‘white genocide’ creates a sense of urgency and of the need for immediate action,” says Rajan Basra, a researcher from the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) at King’s College London.

“For white nationalists this can be a powerful motivator, and time and time again they have violently acted on it.”

Image source, EPA

The Buffalo attacker also posted nearly 700 pages of his private diary, dating back seven months – copies of which the BBC has read.

The logs are a window into the mind of a clearly troubled young man who regularly spoke about his addiction to gaming and surfing extreme online circles.

He carried out extensive research and several reconnaissance journeys to the grocery store in Buffalo to carefully plan the manner and timing of his attack, and practised mock versions.

He briefly mentions getting into trouble with authorities a year earlier after writing something that alarmed them.

3/ The most glaring example came during an online assignment at school, when he was asked the question:

“What do you want to do when you retire?”

The #Buffalo shooter wrote down: “murder/suicide”

— Rajan Basra (@rajanbasra) May 16, 2022 The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.View original tweet on Twitter

There are brief moments of doubt, as he wonders whether he will be able to carry out a mass shooting without “messing up”.

There are also graphic details of an act of animal cruelty and suicidal thoughts for failing to carry out the attack on the date he’d initially planned.

Packed full of racist and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, memes, hoaxes and and in-jokes, his manifesto is also clearly influenced by the message board 4chan, one of the biggest and most controversial hubs of internet subculture. It is the birthplace of many famous online memes, harassment and trolling campaigns, as well as social, political and conspiratorial movements.

Gendron references a 4chan board devoted to guns, and says he was radicalised by the /pol/ or “politically incorrect” board. He also mentions other extreme online spaces he visited, including the neo-Nazi website The Daily Stormer.

The attacker also live-streamed his killings on the video streaming platform Twitch with a camera mounted on his helmet. Like Tarrant, he wrote white supremacist slogans and racial slurs on his firearm.

The stream was only watched by 22 people and Twitch took it down within minutes. However, copies were in wide circulation online within hours, drawing millions of views on Facebook and other platforms.

Maximum impact

The combination of an online manifesto and video livestream is done to generate maximum media impact and spread the killer’s views as far and wide as possible.

Copies of the video and manifesto will probably be shared online for years to come, for propaganda purposes and as a recruitment tool. And although mainstream social networks will remove copies, there are many fringe websites where the video can be easily found.

Eliminating content from the internet is more or less impossible. For instance, after the violence in the US city of Charlottesville in 2017, the neo-Nazi Daily Stormer came under pressure from hosting and web protection companies.

But with enough effort, that site can still be found online, and the Buffalo attacker claims to have been a regular visitor.

And as previously seen with fringe platforms like 8chan – where the manifestos of three killers appeared in quick succession in 2019 – even if access to one website is cut off, new ones will pop up in no time.

“On the internet, there will always be a home – however niche or obscure – for extremist content,” says Mr Basra of the ISCR.

The rambling documents aim to inspire the next racist shooter, just as Gendron himself took inspiration from Brenton Tarrant, and Tarrant from Norwegian neo-Nazi murderer Anders Breivik.

“People once shunted to the fringes can form whole cultic [online] communities around the globe,” says author and journalist David Neiwert, who has been writing about far-right extremism for decades.

“One of the results of this is that far-right domestic terrorism has taken on a chain or serial aspect: one act of violence inspiring the next inspiring the next,” he says.

Federal preventative programmes

In response to the rise of home-grown terrorist attacks, many governments have attempted to draw up counter-terrorism plans to prevent such tragedies.

The UK government’s Prevent scheme is one example. Although criticised for failing to deter some people known to authorities, like Ali Harbi Ali, the Islamist extremist who killed MP Sir David Amess, the government claims it has stopped hundreds of would-be terrorists.

No similar scheme exists in the US. In June 2021, the White House released a national plan for countering domestic terrorism. The plan focuses mostly on law enforcement efforts and includes $77 million in grants for local police forces.

Mr Neiwert says that while US law enforcement is empowered to become engaged when criminal activities are being discussed online, there’s little they can do until a suspect takes action.

The assailant in Buffalo did not fly entirely under the radar. Last year, his brush with the authorities resulted in a short stay in a hospital undergoing a mental health evaluation.

New York state has a law that allows police to confiscate the guns of people considered dangerous. Local police and the FBI will now face questions about whether they could have done more.

But the larger problem remains: a global leaderless movement of young violent extremists, radicalised on the internet, some of whom are prepared to launch deadly attacks against innocent people.