Bud Fowler and “Buck” O’Neil, two baseball greats finally welcomed to Cooperstown

Buck #Buck

For the true fan, entering the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, is like being admitted to a shrine.

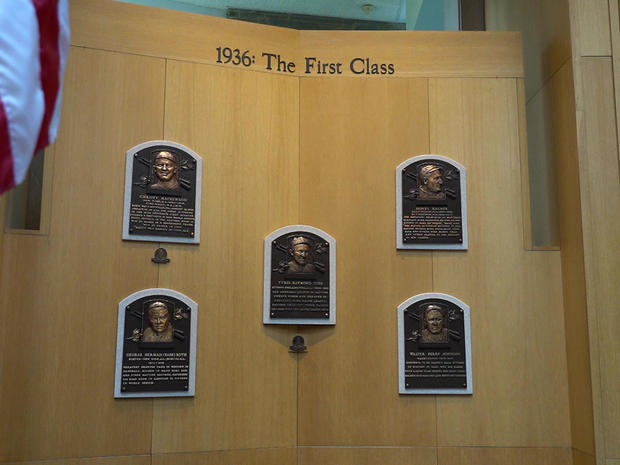

Hall of Fame president Josh Rawitch showed correspondent Mark Whitaker the plaques honoring the patron saints of the game, five gentlemen who were the first class of inductees in 1936: Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Christy Mathewson, Honus Wagner and Walter Johnson.

Cobb, Rawitch said, “got the most votes. That’s why he’s there in the middle.”

They were the greatest players of their era.

The first inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. N.Y. CBS News

The first inductees into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. N.Y. CBS News

The blank spots on a nearby wall will be filled by seven players who are being inducted today – six of whom were chosen by special committees set up to highlight players who haven’t gotten their due. It’s a sign of how the Hall of Fame is increasingly trying to tip its cap to the diverse history of the game.

Whitaker asked, “Is this all an effort to make up for past sins?”

“No, I wouldn’t say it’s an effort for past sins,” Rawitch replied. “I would say it’s really just to make sure that everybody’s given a fair shake. In some cases it may just be that the lens of time has changed the perspective of baseball.”

One inductee coming into focus played way back in the 1870s: John W. Jackson, better known as Bud Fowler. Said Rawitch, “He was the first Black professional player to help integrate white leagues.”

If you thought Jackie Robinson was the first to break the color barrier in 1947, think again: Bud Fowler, a Black player from the Cooperstown area, was playing in white professional leagues 70 years before that.

Yankees Hall of Famer Dave Winfield is going to give the speech this morning welcoming Fowler to the Hall. “He found a game that he loved,” he told Whitaker, “and it was with him throughout his life, as a player, a coach, a promoter, a person who loved the game in a very different time in America.”

“So, he played for integrated teams in that period, after the Civil War, is that correct?”

“They weren’t integrated until he showed up!” Winfield laughed.

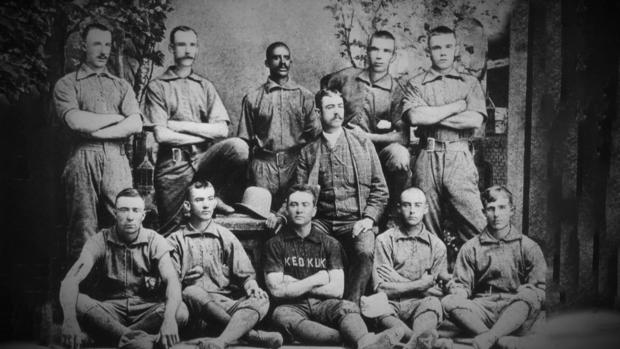

Bud Fowler (top row, center) was the first professional African-American baseball player. Among the teams he played with was the Hawkeyes, the Keokuk, Iowa team of the Western League, in 1885. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Bud Fowler (top row, center) was the first professional African-American baseball player. Among the teams he played with was the Hawkeyes, the Keokuk, Iowa team of the Western League, in 1885. National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Just a few days ago, Winfield visited Fowler’s grave not far from Cooperstown. “He was born in 1858. I know a little bit about my genealogy and heritage, and I know that my great-grandparents were born at the same period of time. Slavery was still intact, how about that? So, I can only imagine what Bud Fowler went through at that time.”

Fowler played alongside whites for about 10 years, before the racial door slammed shut. In 1920 the Negro Leagues formed teams of professional players who roamed the country. One alumnus is another of this year’s inductees: the Cuban-born Minnie Miñoso, who became known as Mr. White Sox. Others include Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and, yes, Jackie Robinson.

Sixteen years ago, the Hall of Fame honored some of the players from back then, inducting 17 Negro Leaguers in 2006. At the time, there was one Negro Leagues veteran who was considered a shoo-in: John Jordan O’Neil Jr., known far and wide as Buck.

Whitaker asked Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, “What was Buck O’Neil like as a player?”

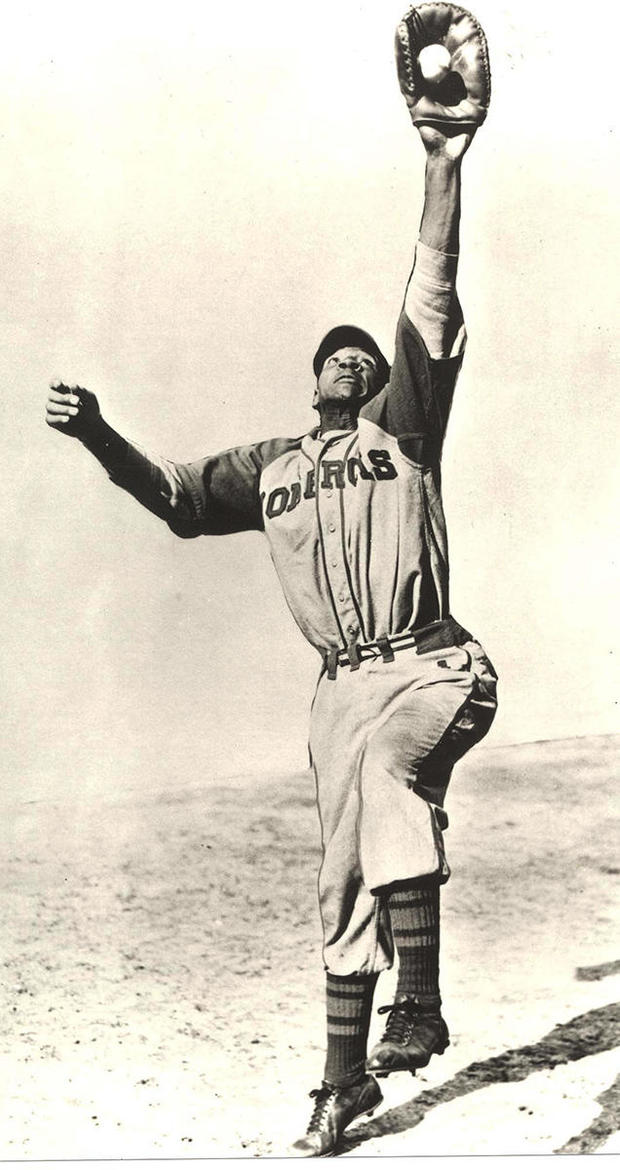

John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil Jr. Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil Jr. Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

“He was an outstanding player. A great defensive first baseman. I think he would be in everybody’s top-five all-time Negro League defensive first basemen. He told me one season in the Negro Leagues he made one error the entire season. If you got it over to Buck, he was going to pick it.”

O’Neil played mostly for the Kansas City Monarchs; then, was a major league scout, and finally the first Black coach in the majors, with the Chicago Cubs. But O’Neil was more than that. He remained a goodwill ambassador for baseball all his life, and co-founded the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

In 1998 he told David Letterman about playing ball as a kid: “My daddy was a baseball player, and I followed him around, watching him play. I always had good hands, see, and the old men would throw me the ball and I would catch it. I was a ham, you know, I enjoyed that!”

Kendrick said, “The thing that I remember most about Buck is that you always felt better leaving Buck than you did when you came to see him.”

Kendrick was with O’Neil when the Hall of Fame class of 2006 was announced – and somehow O’Neil didn’t make the cut: “And I say, ‘Well, Buck, we didn’t get enough votes.’ And he looks at me and he smiles. He said, ‘That’s how the cookie crumbles.’ And he asked me how many had gotten in. I said 17. He hits the table in utter jubilation. He was ecstatic that 17 of his colleagues had gotten their rightful place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Now I, on the other hand, was furious. I’m in disbelief that you could put 17 in and leave Buck out.”

And then, at the age of 94, O’Neil was asked to speak at the induction ceremony for those 17 players.

“I’ve done a lot of things I liked doing,” he said. “But I’d rather be right here, right now, representing these people that helped build a bridge across the chasm of prejudice. … And I’m proud to have been a Negro League ball player. Yeah!”

John “Buck” O’Neil speaks during the Hall of Fame Induction ceremonies at the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, N.Y. on July 30, 2006. Rich Pilling/MLB via Getty Images

John “Buck” O’Neil speaks during the Hall of Fame Induction ceremonies at the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown, N.Y. on July 30, 2006. Rich Pilling/MLB via Getty Images

Said Kendrick, “I’ve oftentimes said that it was one of the most selfless acts in American sports history, because baseball fans were saying, ‘This should be your Hall of Fame induction speech.’ And there was this very kind, gentle man, speaking on behalf of 17 others, all of them dead. They didn’t have a voice. And he became their voice.”

Buck O’Neil died two months after that speech. And now: a do-over. Sixteen years later, he’s finally in the Hall of Fame.

“He was a very special person,” said his niece, Angela Owen Terry, who will give his induction speech.

Whitaker asked, “You said you think the hardest thing about giving this speech is that you might cry?”

“Yes. I haven’t been able to rehearse it without crying.”

“Would they be tears of sadness, or tears of joy, or both?”

“Tears of joy and remembrances,” she replied.

Terry insists there’s no bitterness over the long-delayed recognition. “Well, of course I would prefer that he would be there. However, I have, nor any member of the family, has any lasting disappointment. He is in a place where he knows that he has attained his lifelong dream.”

“You feel like he’ll be there in spirit?”

“Exactly.”

Visitors to the Baseball Hall of Fame are greeted by a statue of Buck O’Neil. Listen closely, and you might hear his spirit echoing – a song he sang at the end of his Hall of Fame speech:

The greatest thing in all my life is loving you.

“Thank you, folks. Thank you, folks.”

For more info:

Story produced by Alan Golds. Editor: Ed Givnish.

See also:

Jackie Robinson, George Shuba, and the “handshake of the century” 06:20 More