‘A well deserved celebration’: Charting Toni Morrison’s path to creativity

Morrison #Morrison

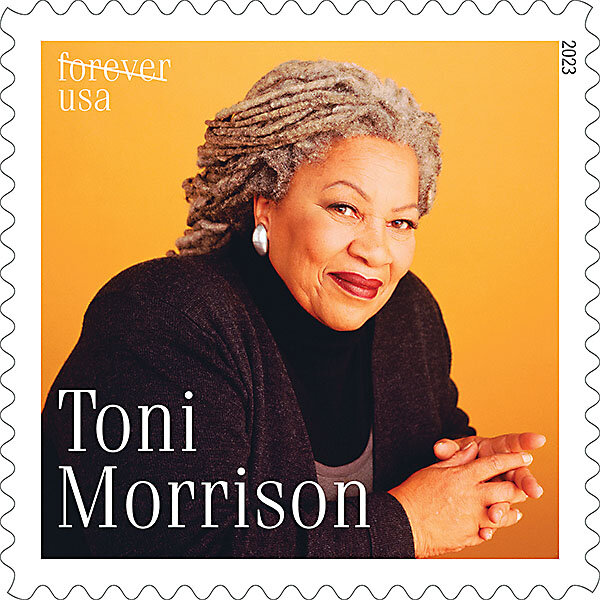

Some school districts are banning Toni Morrison’s books, but Princeton University is celebrating the work of the late author – whose legacy was commemorated this month by the United States Postal Service with a “forever” stamp.

A new exhibit at the school, where Ms. Morrison was a professor, offers a trove of background material on what inspired the Nobel laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner – for “Beloved” – and led to her literary milestones.

Why We Wrote This

Decorated author Toni Morrison’s approach to creativity involved drawing her settings and jotting inspiration on paper scraps. What does her process tell us about her path toward influencing American culture?

“Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” at Princeton’s Firestone Library through early June, draws on archival material acquired in 2014, including manuscript drafts, sketches, musings, correspondence, and photographs.

“Toni Morrison transformed how we, as a culture, talk about history, slavery, and memory,” says the exhibit’s lead curator, Autumn Womack, via email. “A book like Beloved, for example, created an entirely new framework for thinking about how the past is always haunting us.”

“My hope is that visitors will leave with a sense of Morrison’s creative practice,” adds Dr. Womack.

Ilene Renshaw has traveled from nearby Pennington, New Jersey, to come read the musings of one of her favorite authors. After at least 45 minutes of taking in posted material and watching a video, she is satisfied with making the trip to campus.

“This is a well-deserved celebration,” she says.

Some school districts are banning her books, but a prominent American university is celebrating the canon of work by the late Toni Morrison – who won literature’s highest awards and whose legacy was commemorated this month by the United States Postal Service with a “forever” stamp.

Most people turn to her books, like Pulitzer Prize winner “Beloved,” to better understand the author and the history she depicts. But a new exhibit at Princeton University, where Ms. Morrison was a professor, offers a trove of background material on what inspired the writer and led to her literary milestones.

“Toni Morrison transformed how we, as a culture, talk about history, slavery, and memory,” says the exhibit’s lead curator, Autumn Womack, via email. “A book like Beloved, for example, created an entirely new framework for thinking about how the past is always haunting us.”

Why We Wrote This

Decorated author Toni Morrison’s approach to creativity involved drawing her settings and jotting inspiration on paper scraps. What does her process tell us about her path toward influencing American culture?

“Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” at Princeton’s Firestone Library through early June, draws on archival material the university acquired in 2014, including manuscript drafts, sketches, musings, correspondence, photographs, and a taped interview.

“My hope is that visitors will leave with a sense of Morrison’s creative practice, not only what she wrote, but how she wrote, how she moved from what she describes as a question to published masterpiece,” adds Dr. Womack, an assistant professor in the department of English and African American studies at Princeton.

Brandon Johnson/Princeton University Library

Materials on display at the “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory” exhibition at Princeton’s Firestone Library include papers, photographs, sketches, and a video interview.

As a working mother to two sons, the author often had to snatch bits of time to formulate story ideas during commutes to and from work. She kept paper handy in the car to write her musings. “If you know it really has come, then you have to put it down,” she once told the Paris Review.

She collected jottings throughout her career. In a note to herself when she was writing her 1992 book, “Jazz,” Ms. Morrison scribbled a reminder to research the first Black police recruit for New York City and when a gun silencer was first available for purchase. A photo of a girl, labeled “Pretty girl in a coffin,” from a Harlem funeral, is featured near her notes for the book.

Words were her main creative material – but she also drew images. Pencil and pen renderings of interior and exterior scenes detail how she envisioned settings. Her sketch of the house in “Beloved,” set in the 1800s, included its store room, cold room, and bathtubs.

“Seeing her original thought process, to me, is fascinating,” says Kristin Eck, on a visit from Denver to see her daughter, who attends Princeton.

Ms. Eck uses words like “raw” and “emotional” to describe Ms. Morrison’s writing. “I’m from the Midwest. Thinking back to when she’s talking about books or writing, and the things that I read growing up, and how much society steered you away from anything that was open. She was open,” she says about the topics the author explored in her fiction.

Brandon Johnson/Princeton University Library

Curating team Rene Boatman (left), Andrew Schlager, and Autumn Womack work with archive materials at Princeton University.

“The Bluest Eye” is Ms. Morrison’s first novel, published in 1970 and frequently banned for its inclusion of incestuous sexual assault. A typewritten letter from an editor at Doubleday in 1966 urged the writer to continue working on it, but to consider it for short stories instead of a novel. The author’s real-life friend Eunice is the inspiration for the story’s 11-year-old African American main character, Pecola Breedlove, who wishes her eyes could be blue. Descriptions of Eunice come alive in Ms. Morrison’s notes.

“She’s thinking about how to create a character and then how she wants us to read that character,” says Rachel Sturley, a Princeton senior who is visiting the exhibit as part of a presentation for English class on the author’s novel “Song of Solomon.” “So having this context while we’re reading these books and studying in class has been really interesting.”

Ms. Morrison, who was the first African American woman to win a Nobel Prize in literature, says in a filmed interview in the exhibit that her love of reading started in childhood. She explains that even her grandfather – who had no formal education – loved to read and learned by reading the Bible.

On March 7, the United States Postal Service unveiled a new “forever” stamp featuring Nobel laureate Toni Morrison.

Her efforts to publish Black writers such as Toni Cade Bambara and Angela Davis – when she was a senior editor at Random House in the 1970s – shifted the literary landscape and ushered in a new generation, Dr. Womack notes.

“It is hard to overstate the extent to which Morrison influenced American culture,” she explains.

Decades after she was first introduced to Ms. Morrison’s writings, Ilene Renshaw has traveled from nearby Pennington, New Jersey, to come read the musings of one of her favorite authors.

“I have signed first editions [of her books] that I really value,” says Ms. Renshaw, standing near a framed draft of one of Ms. Morrison’s short stories.

She points behind her to a screen where the author is being interviewed and comments on how much she loves her voice because of how distinctive and serene it sounds. After at least 45 minutes of reading through posted material and watching a video, Ms. Renshaw is satisfied with making the trip to campus.

“This is a well-deserved celebration,” she says.