A playbook for the black experience

tannie #tannie

I grew up in what was called a “coloured” location in Pietermaritzburg. There, I quickly got to understand that there was a particular bounce or edge one had to have when wandering around the streets to show you belonged and was not to be picked on.

It was a swagger, accompanied by particular slang words and a manner of dress — baggy jeans — that if I didn’t ascribe to, I’d certainly be picked on for either my “bus head” or my African “snot”, as a result of my darker skin colour.

It’s something that I wasn’t very good at pulling off — I mean, how does one have a bounce on one specific leg, and not look silly in the process, or wear T-shirts back to front without looking ridiculous to one’s older siblings?

Still, I managed an air of cool. I’d like to imagine a cool enough air to let me enjoy my childhood in Woodlands, my Idaho on the perimeter of my small town.

My mother, who was exposed to much of this attempt to find street cred, would be most amused by her only son’s attempts at fending off the dangers of that little township, where “Danny Boy” from Ghost Town would every now and then chase my best friend, Marvin, and me home from school — just because of our geekiness, I suppose.

There were many ground rules for my behaviour on the streets of my little world and, more critically, outside the local grocery store where some of the older Jack Purcell-wearing boys and men gathered to smoke cigarettes all day, in the absence of anything else to do, because the few textile and woodwork factories that surrounded my neighbourhood were shutting down as cheaper Taiwanese and, later, Chinese goods flooded into the country in the early 1990s.

No matter how small one’s chest — and mine was critically small — you had to push it out, and I pushed mine out as if I owned the piece of earth my little feet were walking on.

Notorious B.I.G perfroms

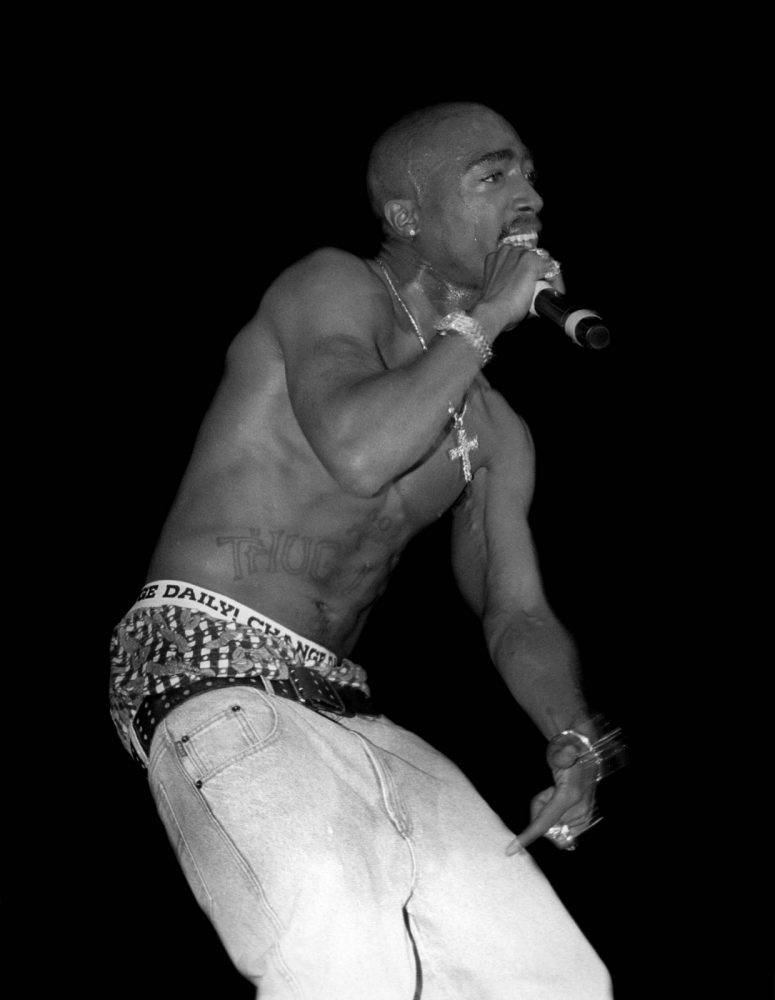

Notorious B.I.G perfroms  Tupac Shakur performs

Tupac Shakur performs  Jay-Z performs

Jay-Z performs

In truth, you just didn’t want to be too noticeable or appear too meek or your bike could get stolen when you inevitably had to leave it outside Tannie’s shop while buying a loaf of bread. Mine was stolen. Enough said.

I thought about these images of my big-headed self, with a Zulu-speaking family in an “English’’ ghetto, in the final throes of the abnormal racial and economic experiment that was apartheid, and just how important it was that I subscribe to a playbook of how to act to thrive or, at the very least, survive, without being constantly challenged on my toughness — an exhausting enterprise.

It’s a playbook that I imagine every young black child in an urban setting had to ascribe to as our parents flocked to urban centres despite designs meant to keep them out or in the “bantustan” experiments that emerged in the early 1970s.

By apartheid design, interaction between the races had to be minimal and especially with white South Africans. Black people had to be kept far away from the cities, transported in and out by trains, buses and taxis. It was an experiment bound to fail by simple arithmetic as townships grew bigger and ever closer to cities where, much like in the US, the white populace had escaped to suburban bliss.

If we take it on a broader scale, over the past two decades, cities and towns across Southern Africa have grown by 100 million, with reports that there are about 179 million people living in urban spaces today — 47% of the region’s population.

This migration exposes the difference between my parents’ generation, and mine — they had to navigate very different growing pains.

Their environment, especially that of my father, was the rolling hills of KwaZulu-Natal while mine was the hard tar of an urban landscape with many different shades of black, and in my early teenage years, white South Africa in Model C schools when they opened to me at the advent of democracy.

I had to have a different playbook to my father’s and hip-hop fit the bill — it was a cloak.

When watching the early music videos of DJ Jazzy Jeff (Jeffrey Townes) and The Fresh Prince (Will Smith) in the 1980s, I saw a sass in young men not much older than myself that I could emulate. They carried an air of confidence in navigating their urban jungle and made black the cool thing to be.

Michael Jackson was just too Neverland to be real for my generation. But here were two of the most commercially successful rap artists of the time, rapping with Tempo haircuts, colourful T-shirts and baggy jean-shorts that said, “Looking like me is cool — and I belong.”

Simply, there was nothing to apologise for about being black.

Inspiration: The videos of DJ Jazzy Jeff in the 1980s showed that black was the cool thing to be. Photo: Brian Stukes/Getty Images

Inspiration: The videos of DJ Jazzy Jeff in the 1980s showed that black was the cool thing to be. Photo: Brian Stukes/Getty Images

When I was no longer going to school in the relative safety of my “coloured” township, and became part of the experiment of multi-racial schooling in the very early 1990s, hip-hop and its culture would become a much, much more important playbook, in particular its harder edges, when dealing with a new sort of bully, prone to calling me “kaffir”.

When Eazy-E (Eric Wright) brought his gangster rap to form N.W.A. with the legendary Dr Dre (Andre Young), the red plaid shirts made famous by Snoop Dogg in the videos from his critically acclaimed Doggystyle album were the clothes to wear every casual day at Linpark High in Maritzburg.

The message being sent by my motley crew — of two, really, me and my best friend Sifiso — was that we weren’t to be messed with.

On my pencil case, I remember writing, in Tipex, New York giant Notorious B.I.G.’s line “Black and ugly as ever” to express my edgier side, to impress upon whoever read it how dangerous this skinny 14-year-old was.

It didn’t work too well on my favourite English teacher. For this was all theatre, really, as I admit all I cared about was some good laughs, girls, football, rugby and for Sifiso to continue dominating athletics to attract more girls.

There were no thoughts of carrying guns or representing gangs — such as the Crips or the Bloods in Los Angeles thousands of kilometres away — which was, and continues to be, the hallmark of West Coast rap.

Between the ages of 14 and 16, I experienced the loss of both of my parents and my taste in hip-hop changed, looking for a darker moon, perhaps.

That’s when the late Tupac Shakur swallowed me whole. His music spoke primarily of his own death, and the pain of loss. It was of great comfort and shadowed me throughout my teen years. It led to a dropping of my shoulders and dragging of my feet as I contemplated the great loss of my life.

I started emerging from this very cold winter as South Africa’s transition was playing out against a backdrop of a buoyant economy, and the Africa-first narrative of Thabo Mbeki’s early administration, and hope of better, more conscious, rappers such as The Roots and Common took hold.

By this time, the plaid shirts of Snoop Dogg had long gone and there was a return to wearing belts, at the very least, which would have pleased my father no end.

By this time, a South African interpretation of hip-hop had matured to better incorporate local musical tastes. TKZee, Stoan of Bongo Maffin and the late, but not forgotten, Zimbabwean rapper Mizchif had begun to make hip-hop our own.

The likes of HHP, Tuks and the whole Maftown gang made it fashionable to rap in Setswana. KwaZulu-Natal also had a huge hip-hop base. They were the inspiration for latter-day heroes, such as the K.O, Cassper Nyovest and the late AKA.

Today, standing as the embodiment of hip-hop and its 50-year journey is Jay-Z. He, of all the many practitioners of the art form, encompasses the journey from a “black male misunderstood” to one who has finally been understood.

He went from selling drugs on the streets of Brooklyn as a 13-year-old to becoming a man respected for his art and his business acumen. It’s a path that could have easily seen him end up in Rikers Island prison like many of his peers who pounded the hard concrete pavements of New York.

Anyone who has followed hip-hop understands the importance of Jay-Z to the art — he is to hip-hop what Miles Davis is to jazz, Frank Sinatra to swing and big band music.

He is the most updated playbook of how to navigate the urban jungle for a “black male misunderstood”, as the The Notorious B.I.G. once rhymed.

The genre will have other totem poles. I imagine men such as Burna Boy or Wizkid from Nigeria might lead that charge as the rapidly urbanising African continent gains traction in global culture.

The growing prominence of our own amapiano tells of how much of an influence the continent will have on how black children carry themselves, not only in Johannesburg, Lagos and Nairobi, but in New York, Los Angeles, Paris and London.

They are competing and, to some extent outperforming, Travis Scott, Kendrick Lamar, Childish Gambino, Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion, who are America’s younger crop of hip-hop ambassadors.

Hip-hop is black urban culture, a cloak for any young person finding themselves in a new world, with rules on slang, dress and, most importantly, attitude.

Hip-hop’s home isn’t New York. At its core, it’s a mic to black lives in the latter half of the 20th and the 21st centuries.