How Disney and Warner Bros. Are Causing Internet Piracy to Boom

Warner #Warner

In our digital era, movies and T.V. shows were supposed to get easier to watch, not harder. But it turns out, media companies are fickle—and media distribution can get complicated as it crosses borders.

Warner Bros. Discovery has purged a bunch of high-profile movies and shows, either canceling them in post-production or deleting them from the Max platform. The sci-fi show Westworld disappeared from Max after its fourth and final season. WB killed off the completed superhero flick Batgirl without ever releasing it. Hulu, Disney+, and Paramount+ have also conducted their own, smaller purges.

So what are a viewer’s options when a studio or streamer abruptly yanks a film or series from distribution or, eyeing a tax writeoff, cancels it right before release? These issues are also compounded as physical media like DVDs and Blu-rays disappear from more and more stores and movie-distribution remains fractured by geography.

For a growing number of people, the answer is: steal it. After dipping in recent years, online piracy is on the rise again. And a not insignificant contingent of filmmakers and their fans believe this theft is justified.

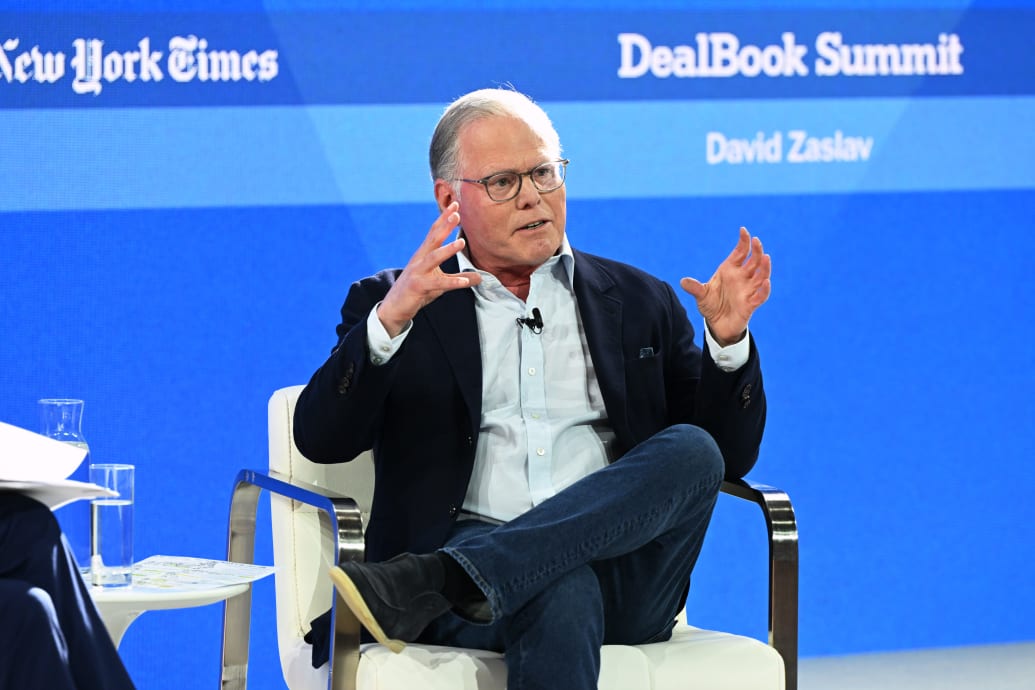

David Zaslav speaks onstage during The New York Times Dealbook Summit 2023 at Jazz at Lincoln Center on Nov. 29, 2023 in New York City. In Jan. 2023, he told reporters at Variety that the “Batgirl” movie wouldn’t be launching on any platforms because it was “unreleasable.”

Slaven Vlasic/Getty Images

Actor and director Werner Herzog may have best expressed this attitude. “Piracy has been the most successful form of distribution worldwide,” Herzog said at a Swiss film festival in 2019. He was responding to a comment from Ukrainian movie-producer Illia Gladshtein, who admitted that while in Ukraine he could only get ahold of Herzog’s movies via torrent websites.

Torrent sites allow users to quickly download large files. Today they’re synonymous with T.V., music, and movie piracy.

“If you don’t get [movies] through Netflix or state-sponsored television in your country, then you go and access it as a pirate,” Herzog said. “I don’t like it because I would like to earn some money with my films.”

“But,” he added, addressing Gladshtein, “if someone like you steals my films through the internet or whatever—fine, you have my blessing.”

Herzog isn’t alone in giving his blessing to piracy, when piracy is the only way to watch a certain movie in a certain country. “I don’t pirate much, but I honestly don’t care if people do,” Alfred Giancarli, the New York City-based director of the award-winning drama Weeknights, currently on the festival circuit, told The Daily Beast.

“The people I know who do [pirate] are some of the most rabid cinephiles I know.”

— Alfred Giancarli

“I think there are lots of reasons why people download or use digital file sharing to access movies,” Giancarli said, “from ease-of-use, cost- and space-saving, because the film may not be available where they live or may be too expensive to obtain through traditional means.”

But Giancarli noted an ironic twist: “The people I know who do [pirate] are some of the most rabid cinephiles I know.” They’d happily pay for a movie if they could.

Herzog and Giancarli aren’t alone in reaching this conclusion. “The irony of this situation is that the most avid [paying] consumers are also most likely to pirate,” Ernesto Van der Sar, the editor of the trade publication TorrentFreak, told The Daily Beast. “They simply can’t pay for everything they want to see.”

“In a way, it makes sense because people who are not interested in films [or] T.V. have no intention to pirate, either,” Van der Sar added.

Piracy of movies and T.V. shows really took off when torrents first appeared in the early 2000s. It seemed to peak five or six years ago, as new streaming services proliferated.

This made sense. Streaming promised to make practically every movie and show available to everyone, all the time. Sure enough, The Software Alliance—a Washington, D.C. anti-piracy organization—claimed digital piracy declined by 37 percent in 2017.

According to the European Union Intellectual Property Office, piracy bottomed out in 2021—before increasing again. “Current piracy levels are still nowhere near what they were five years ago,” Van der Sar wrote in a recent article. “However, a trend reversal is notable and may suggest that we’re at a pivotal point in time.”

Geography is a factor. Studios sell media-distribution rights by territory for defined spans of time. One distributor might handle North American distribution for a particular film for 10 years while another sells the same movie in Europe or Asia, but only for five years.

In other words, certain media is available in certain countries at certain times. These licensing “silos” help explain why, for a while, you could watch Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight on Netflix in the U.S., but not in the U.K..

But the industry’s own fickleness is to blame, too. “Streaming services have the power to promote or bury movies based on their objectives,” film critic Travis Bruce told The Daily Beast.

It might not make sense to movie fans that Warner Bros. would prefer to cancel the completed Batgirl than to release it, even after spending $90 million to make the film. But it made sense to Warner Bros. The company described the cancellation as part of a wider “restructuring” it anticipated would help it save $2 billion.

Most people don’t care about corporate restructuring. They do care about movies and T.V. shows—and the growing difficulty of finding some films and programs. “Subscribers feel exhaustion and frustration when they can’t access ‘their content,’ or when titles—even titles produced for a streaming service—are dropped from that streaming service, or when titles bounce around from one streamer to another,” Giancarli said.

Not everyone turns to piracy when a streamer abruptly drops a movie or show. While overall sales of DVDs and Blu-rays are still declining—and could take a big hit next year when Best Buy removes the last discs from its shelves—some movie distributors report a growing interest in physical media from the most committed cinephiles.

“The streaming industry has to converge towards a system where consumers can watch pretty much everything they like for an affordable price.”

— Ernesto Van der Sar, TorrentFreak

After all, you can’t lose access to a film if you own it. “People are always surprised when we tell them that we still pick, pack, ship, and sell DVD movies every day in quantity,” Sam Napolitano, the vice president for sales at BayView Entertainment in New Jersey, told The Daily Beast.

“The market will hit a bottom,” Napolitano said, “but for quality movies, we are not there yet. The market will start to pick up again as a new generation of film-lovers with disposable income will find that they can actually own a physical piece of their favorite movies.”

But not every distributor bothers to release a new movie or show on DVD or Blu-ray. And some older films or programs might be on some out-of-print DVD, but aren’t on the newer, higher-resolution Blu-ray format.

If a movie or show isn’t on streaming or currently in print on some physical media, what’s a fan to do—if not steal? There’s an obvious way for the industry to head off this theft. Obvious, but not simple.

“The streaming industry has to converge towards a system where consumers can watch pretty much everything they like for an affordable price,” Van der Sar said. “That sounds straightforward, but in an industry that’s built around licensing silos with billions in revenue at stake, that’s easier said than done.”