“Stats Bros” Are Sucking the Life Out of Politics

Nate Silver #NateSilver

Politics / September 12, 2023

In their attempt to serve as objective purveyors of fact and reason, Steve Kornacki, Nate Silver, and other data nerds are misleading the left-liberal electorate.

Ad Policy

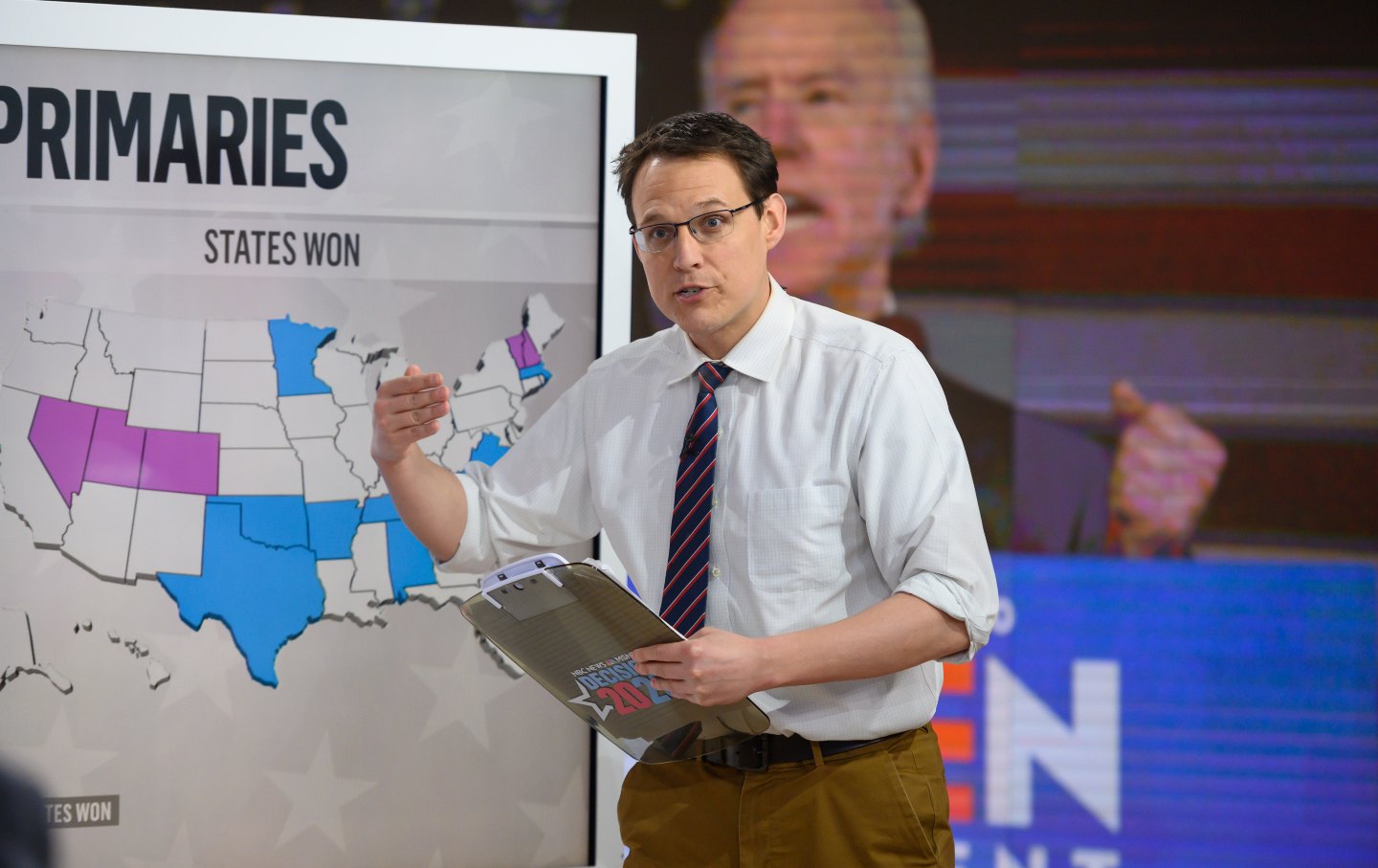

Steve Kornacki.

(Nathan Congleton / Getty Images)

As we stare down another presidential election cycle, I have been reminded of that week in November 2020: Steve Kornacki, awake for several days, was jumping up and down at MSNBC’s infographic board, pointing breathlessly at counties in Nevada and doing mental math as the votes rolled in. His nerdy charisma made him the object of liberal heterosexual lust, and he briefly became “Twitter’s boyfriend.” He seemed, for a moment, like a hero. And it all worked out: Biden won the election by more than 70 electoral votes and four meaningless popular-vote percentage points.

That week plays on a reel like a sentimental movie in the memory of the American liberal: fear, loathing, and relief. But the irony is that while Kornacki was wildly gesticulating at pie charts, it was already over—Biden had won on Election Day. Kornacki in the end, was not predicting anything, but rather telling us a weird story about how vote-counting works in this country.

Rather than a system wherein we learn the result of an election all at once, we have a numbers theater based on which counties in Iowa or Nevada are slowest to report. Don’t get me wrong: I was glued to cable news right through to the call on November 8, but the nervous and hopeful energy was all manufactured. In the United States, these types of election data performances are more histrionics than science. And they go beyond just generating Election Day anxiety; they’re helping to destroy left-liberal politics.

Over the last decade or so, we’ve seen the rise of a media figure I like to call the “stats bro.” Around the 2008 presidential election, Nate Silver, now a best-selling author of books on social statistics, burst into political commentary by using sophisticated algorithmic techniques to crunch polling data and predict elections. Nate Cohn, who heads up the stats section at The New York Times, has established, taken down, reinstated, and endlessly commented on the “needle,” which gives live percentage calculations of candidates’ chances both before and as election results pour in. These men—and they’re always men; usually white, middle-aged, establishment liberals—cut a charming, yet sober, figure in a polarized political landscape.

Stats bros claim to be the foil: “epistemically modest” purveyors of fact and reason. In reality, they conflate data and politics, taking their tools for precise descriptions of the actual world, all the while tending to the neuroses of the liberal electorate. In 2016, Silver’s statistical model gave Trump better chances than other predictors were willing to, grasping that working-class votes across the Midwest would cause a domino effect across the country. This fact is crucial to understanding our political landscape today, but it’s one part, not a whole: Silver’s model told us nothing about why Democrats fumbled the bag on the working class.

Theodor Adorno accused philosophers called “positivists” of the same mistake: They posited a reality and could not distinguish their methodology from the real world. Stats bros need to understand that politics isn’t data; it’s passion, stories, and rhetoric.

When stats bros claim to be “epistemically modest,” they’re articulating a politics we might call the “statistical center”—a voice that promises to provide knowledge backed up by “objective” data to fight increasing misinformation. The promise is well-intended, but it has gone badly wrong.

Silver’s rise to prominence after a series of successful predictions in the 2008 national election has been part of a more general trend toward a statistical method named after the 18th century theologian Thomas Bayes, who included subjective expectations—or “priors”—in probability calculations. Bayes included them in his new mathematics of probability because he saw that humans are not all-knowing, and that imperfection is a part of the world. Bayesian techniques are used widely in our data-heavy era, not only in politics and sports but also in finance and artificial intelligence. The breadth of digital data at our disposal allows statisticians and data scientists to press “refresh” continually, updating our collective priors by producing endless snapshots of markets, politics, and games.

Bayesians tend to think that this refreshing action is what thinking in general is. Silver, who came to politics from baseball statistics, goes a step further, reducing thinking to gambling. In his 2012 book, The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail—but Some Don’t, he claims that “the most practical definition of a Bayesian prior might simply be the odds at which you are willing to place a bet.” I think of this as “casino cognitivism.” Silver exemplifies this metaphor with recommendations for betting on politics, as when he tweeted that “shorting RFK nomination is the freest money on earth.” The stakes of prediction are clear here: They are not meant to foster a healthy political culture, but instead are thought to be accurate enough to put money down on outcomes.

In sports fandom as in election watching, being inside the stats machine is like driving with Google Maps. Digital maps update as you go, using real-time data collected mostly from other drivers. While it’s not actually using Bayesian techniques, it shares something in common: updating predictions at every point in your drive. This isn’t as much a “prediction” as a digital child shouting “Are we there yet?” every 30 seconds. A constantly updated prediction isn’t about the future, it’s about where we are in the present. Everyone knows what it’s like to see that predicted time of arrival slide later and later into the future while sitting in traffic caused by a new road accident. This type of “prediction” isn’t really what we mean by that word, or what we want from a forecast. I needed to know when I left how long it would take to get there.

The statistical center has made politics like Google Maps: You want to know something that’s only possible to know once it happens. But the stats bros are treated as though they know what the future holds, when what they’re really doing is refreshing a data-driven picture of what’s happening now, modeled on what’s happened in the past. This might help you if you’re betting on how fast you can drive somewhere, but getting better at betting on politics isn’t exactly where we should be focusing our attention.

Ad Policy

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Stats and models allegedly make us “less wrong,” but politics isn’t about being right. Facts play a subordinate role to social goals in politics. This is why the overwhelmingly technical rhetoric the stats bros use is depoliticizing: The stats “know the truth,” and you probably can’t change them by trying, so you monitor the needle and you refresh FiveThirtyEight in hope and panic. The infographic doesn’t inform us about politics so much as it becomes its own form of politics.

Bayesianism, because it takes account of beliefs, including wrong ones, “revises” those “incorrect beliefs and quite wrong priors towards the truth in the end,” Silver tells us in The Signal and the Noise. But this tendency toward truth didn’t cause John Podesta to move resources into the Great Lakes states in the fall of 2016; it just gave readers of FiveThirtyEight a sense of satisfaction. Data should be useful, but it’s not clear that predictions really help voters or politicians.

On August 1, researcher Will Stancil tweeted that the economy was getting better under President Joe Biden, but Biden wasn’t getting more popular because of it. He was invoking the logic of Reagan’s famous quip, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” Or in other words, the logic that when the economy gets better, the president should be popular. This observation may have proven uncontroversial had Stancil not tacked on a snide aside: “This raises the question of where people get their ideas about politics, because it sure isn’t objective observation.” Angry exchanges have still not abated after more than a month. Stancil’s surprise at the difference between “people’s politics” and “objective observation” is symptomatic of a liberal culture lulled into data slumber. Rather than give people ways to be “less wrong,” the statistical center has performed “objectivity” about politics in a way that tempts liberals—and rarely conservatives—to think that the reality of politics lies in the data and the models, rather than with the people.

Over the past year, the numbers-centric crowd has bandied about the term “vibecession,” suggesting that real economic conditions are actually good, while only the “feelings” of average workers are inexplicably pessimistic. Voters say they are better off now than they were in 2020, but that the economy is bad anyway. The mainstream media has tended to blame this situation on the housing market and gas prices, as well as the spike in inflation over the last few years. Only the truly data-brained could think that “doing better since 2020” means anything like an overall optimistic view. Wages haven’t grown with wealth and capital over the last 50 years, and “high employment rates” don’t necessarily mean good jobs. This is the kind of tunnel vision data can produce, and “vibes” will always be better than the data when the data is collected by people operating in a vacuum. Stancil and his ilk gawking at the economy gets us nowhere. Data abstractions can be valuable only if we put them in the context of the end of the welfare state and the degradation of workplace protections in favor of capital.

Politics isn’t data; it’s stories: You can’t eliminate rhetoric and passion from the political arena, and you can’t observe them entirely in forecasts either. In their performance of objectivity, stats bros tend to disdain left populism and restrain the kind of ideas that we need to survive as a republic. Being “less wrong” is a selfish goal, not a social one: It serves to allay anxiety about the most important things happening in our world, but not to engage us in those things. We need politicians and voters to have a public dialogue about what social goods are necessary and how they can be realized, not just worry about how many white middle-class women exist in purple state suburbs.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t analyze political data: The last thing we want is a leftism based entirely on “vibes.” Even Adorno thought positivism was better than Romantic politics that slides easily into fascism. We should be harnessing stats for political purposes and using them in the service of ambitious social programs. Politicians should use polling data to see what’s needed to convince people. But we can’t do that by limiting our political imagination to trends.

If stats bros and their followers don’t step back from the spreadsheet and take a wider look, they will leave the majority of the US electorate with a profound misunderstanding of the politics of the moment. While Democrats are trying to tweak numbers, the increasingly unhinged right is engaging in a real political campaign that will destroy our democracy and probably our species. It’s up to the left to overcome data-driven tunnel vision to implement a politics for the future.

Leif Weatherby

is associate professor of German, director of Digital Humanities, and founding director of the Digital Theory Lab at NYU.