Fernando Botero, Colombian artist of rotund and whimsical imagery, dies at 91

Fernando Botero #FernandoBotero

Comment on this storyComment

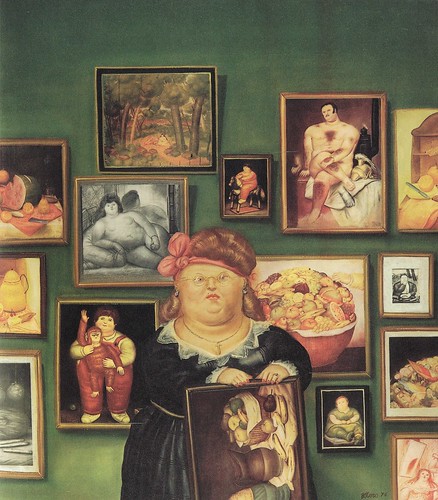

Fernando Botero, a Colombian artist who developed a signature style painting rotund, inflated yet sensuous figures with a whimsical or satirical edge, and who branched into monumental sculptures that adorned some of the world’s most iconic boulevards, died Sept. 15 at a hospital in Monaco. He was 91.

Mauricio Vallejo, co-owner of the Art of the World gallery in Houston and a close friend of Mr. Botero, confirmed the death and said the artist had pneumonia and Parkinson’s disease.

Mr. Botero’s aesthetic — often shorthanded as Boterismom— became a major draw at contemporary art museums and decorated the Champs-Élysées in Paris, Park Avenue in New York and Madrid’s Paseo de Recoletos, among other renowned thoroughfares, as well as parks and plazas from Buenos Aires to Moscow to Tokyo. His emblematic oversized figures helped turn global attention to Latin American artists in the second half of the 20th century.

With deadpan irreverence, he scoured Colombia’s bourgeois urban scenes for imagery of extravagance, pomposity and greed. Mr. Botero early in his career seized on sharp visual contrasts: Tiny snakes, parrots, flies, and bananas adorn his portraits of blimpy bullfighters, bishops, prostitutes, acrobats, ballroom dancers and politicians. Men with rotund faces sport tiny mustaches; hefty ladies smoke miniature cigarettes.

His figures on the canvas and cast in bronze were often voluptuous and slyly fanciful, although he would turn later to darker themes inspired by current events, such as drug violence in Colombia and torture at the U.S.-run Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

Mr. Botero’s work was highly popular and could fetch millions of dollars. Critics, however, especially in the 1960s, did not always approve of his work. Some dismissed it as gimmickry or caricature. An ARTnews reviewer once belittled his enlarged figures as “fetuses begotten by Mussolini on an idiot peasant woman.”

Edward J. Sullivan, a New York University professor who specializes in Latin American contemporary art, traced such animosity to the humor and accessibility of Mr. Botero’s public art installations, which challenged an establishment that often embraced inscrutability and jealously guarded its gatekeeper role.

“My popularity has to do with the divorce between modern art, where everything is obscure, and the viewer who often feels he needs a professor to tell them whether it’s good or not,” Mr. Botero told the Los Angeles Times. “I believe a painting has to talk directly to the viewer, with composition, color and design, without a professor to explain it.”

Mr. Botero’s cheekiness showed in his paintings of Marie Antoinette sauntering through the cobble-stoned street of a Colombian town, a humongous ballet dancer on tiptoe at the barre, and a serious-minded cleric lying in comical repose in a park. In a self-portrait, Mr. Botero depicted himself in full bullfighting regalia.

He rejected suggestions that he should move beyond the voluminous figures in his paintings and his bulbous sculptures.

“Everyone says, ‘When are you going to change styles?’ This makes me laugh,” Mr. Botero told the Miami Herald in 2000. “El Greco painted El Grecos his whole life. El Greco didn’t paint Michelangelos or Giottos.”

Fernando Botero Angulo was born in Medellín on April 19, 1932, the second of three siblings. His father, a salesman who sometimes made his rounds on horseback, died of an apparent heart attack when Mr. Botero was 4. His mother, a seamstress, struggled to maintain the family.

An uncle enrolled Mr. Botero in a bullfighting school, where pupils practiced passes before imaginary bulls. “We were about 20 pupils in the school. After much training, one day, the professor finally said, ‘Now, we’re going to experience with a real bull.’ Nineteen left the school, me included,” Mr. Botero told the South China Morning Post.

He began sketching scenes from the bullring, finding a passion outside his Jesuit school, where priests, scandalized by an admiring essay he wrote on Spanish artist Pablo Picasso, expelled him in 1949.

Mr. Botero graduated from a public high school, eventually moving to Bogotá, the Colombian capital, a breathtaking experience that thrust the young artist into a creative milieu — artistic and literary — far removed from provincial Medellín. When one of his paintings placed second at a national competition in 1952, he used the prize money to study art in Madrid.

He visited the Louvre in Paris and settled in Florence in 1953, delighting in Renaissance paintings. But upon returning to Colombia in 1955, Mr. Botero bombed in his efforts to sell his work.

Mr. Botero and his first wife, Gloria Zea, moved a year later to Mexico City, where Mr. Botero seized on what would become his signature style. A Botero painting from this era — depicting a mandolin with an improbably tiny sound hole that made the instrument appear out of proportion — signified the artist’s exploration of volume.

He told the South China Morning Post that he resented the tendency among some viewers to dismiss his subjects as fat. “For me, it’s an exaltation of volume and sensuality,” he said. “I’ve done the opposite of what most artists do today — I’ve given importance to volume. I’ve also given importance to subject matter and expression — poetry. I don’t want to shock people. I want to give them pleasure.”

His movement toward a more exuberant style grew upon his return to Bogotá, where artists and writers were beginning to blur the lines between the real and the fantastical. The movement would explode by the 1960s into a genre known as magical realism and most associated with the writer Gabriel García Márquez, a contemporary of Mr. Botero’s who won the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature.

“You can’t really understand the spirit of Botero without taking into consideration what obviously people like García Márquez, whom he knew, of course, were doing,” said Sullivan, the art historian. “It was really a small but hugely vital world. . . . García Márquez saw Botero’s paintings and drawings and profited, I think, quite a bit from that.”

Mr. Botero moved to New York in 1960, the year he divorced, but generated little interest among artists and buyers. “The great passion in America and the world was abstract expressionism,” he told Bloomberg TV in 2014.“But I remained loyal to my ideas.”

He was selling paintings for $200 to $300 each, barely making ends meet, until a curator for the Museum of Modern Art happened to see one of his pieces during a visit with another artist who lived in Mr. Botero’s building. The museum bought Mr. Botero’s “Mona Lisa, Age Twelve,” an interpretation of da Vinci’s masterpiece, and immediately boosted Mr. Botero’s stature.

Mr. Botero’s second marriage, to Cecilia Zambrano, ended in divorce. In 1978, he married Greek sculptor Sophia Vari; she died in May. Survivors include three children from his first marriage, Fernando, Juan Carlos and Lina; a brother; and several grandchildren.

Pedro, his 4-year-old son with Zambrano, was killed in a 1974 car accident in Spain while Mr. Botero was driving. “You know the barrier, in the middle of the autostrada? It fell on my car, killed him instantly,” he later told the South China Morning Post. “The whole family was lucky not to be killed.”

Mr. Botero lost parts of two fingers and some movement in his right arm, but grief propelled him into a frenzy of work, and he said the best painting he ever made was of his late son. “I still had the bandages on when I painted it,” he said.

In his later years, Mr. Botero lived and worked in Paris, Monte Carlo, New York and Pietrasanta, Italy. He routinely visited Colombia but grew alarmed by its rising levels of drug trafficking and violence in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1994, a squad of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, a Marxist guerrilla group, failed in a bid to kidnap Mr. Botero.

A year later, insurgents set off a bomb near his open-air bronze sculpture “Pájaro,” or Bird, which he had donated to his home city. The blast struck during an outdoor concert and killed more than 20 people.

Amid the violence, Mr. Botero, who had successfully returned to painting, took on more overtly political subjects. A series of paintings showed Pablo Escobar, the head of the Medellín narcotics cartel, dying on a rooftop in a hail of police bullets. Others portrayed car bombings, a rebel leader clutching an automatic weapon in a jungle clearing, a bar massacre, a kidnapping and other scenes of mayhem — usually without the mocking or satirical style of some of his other work.

He hoped, he told the New York Times, that his work would “be a testimonial to a terrible moment, a time of insanity in this country.”

In 2000, Mr. Botero gifted the nation artwork valued at more than $100 million, including 200 of his own works and scores of pieces by Chagall, Picasso and Dalí from his private collection. The works are now on display in the Botero Museum in Bogotá and the Museum of Antioquia, in Medellín.

The plaza in front of the Medellín museum, named for Mr. Botero, was the site of the 1995 terrorist bombing. After that attack, Mr. Botero donated a sculpture nearly identical to the one that was destroyed, “La Paloma de la Paz,” or the Dove of Peace. His only condition: that the mangled remains of the earlier sculpture remain standing nearby to remind Colombians of their tragic past.