Robbie Robertson obituary

Robbie Robertson #RobbieRobertson

In the autumn of 1968, when rock music seemed in imminent danger of succumbing to excess of all kinds, a single album – the Band’s Music from Big Pink – provoked a wholesale reconsideration of its priorities. As well as implying a claim to special status, the group’s name was chosen to suggest the ego-less collective endeavour of five individuals, four Canadians and one American. By the time the Band made the cover of Time magazine in 1970, however, Robbie Robertson had emerged not just as their guitarist and chief songwriter but as their musical architect and the engine of their ambition.

Robertson, who has died aged 80, was a superlative guitarist who restored a sense of economy to a craft that had become obsessed with empty virtuosity. As a songwriter, he created small masterpieces of mood, character and narrative, tailored to the expressive voices of Levon Helm, the Arkansas-born drummer who delivered The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down as if the civil war were a personal memory, of Rick Danko, the bassist, who invested It Makes No Difference with ineffable sadness, or of Richard Manuel, the pianist, who evoked a lost world of backporch comfort and joy in Rockin’ Chair.

When he had them alternating verses and singing choruses together, as in The Weight, their first single, Robertson created a kind of rough-hewn vocal polyphony influenced by gospel groups but new to rock music. “I pulled into Nazareth, was feelin’ ’bout half-past dead” was the memorable line given to Helm, the first of the three lead voices, opening a song whose lyric revealed Robertson’s love of southern gothic novels – William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor – as well as the influence of his friendship with Bob Dylan.

The Band, left to right: Garth Hudson, Robertson, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel and Rick Danko, in June 1971. Photograph: Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns

Refreshed by the wellsprings of blues, rockabilly, country as well as gospel, the homespun sound of that first album offered a paradoxical but convincing vision of an older America as a signpost to the future. Practically overnight, having seen the Band dressed as gamblers, outlaws and backwoods preachers from the previous century, a significant proportion of the rock world ditched its silk blouses and snakeskin boots along with overextended displays of instrumental prowess.

The Band’s apotheosis came in 1976 with a gala concert filmed by Martin Scorsese and released two years later as The Last Waltz. In San Francisco’s Winterland ballroom they were joined on stage by a galaxy of stars, including Dylan, Joni Mitchell, the Staple Singers, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, Eric Clapton and Neil Young.

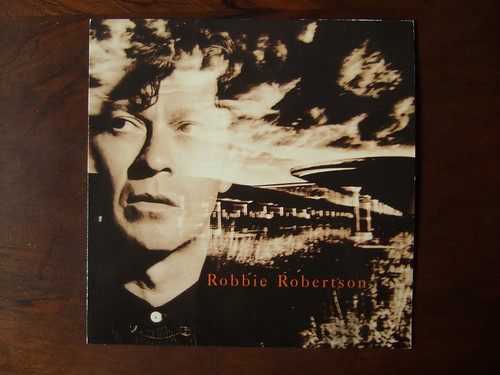

Robertson would embark on a solo career, beginning with an eponymous album in 1987, featuring his own singing, and a hit single, Somewhere Down the Crazy River, followed in 1991 by Storyville, while his interest in cinema and his friendship with Scorsese would lead him to work on the music for such films as Raging Bull, The King of Comedy, The Color of Money, Casino, Gangs of New York, The Wolf of Wall Street and The Irishman.

He was the only child of Rosemarie (nee Chrysler), known as Dolly, and James Robertson, both workers at a Toronto metal-plating factory. Dolly, of Mohawk and Cayuga descent, had been raised on the Six Nations Indian reserve, where her son heard the campfire stories that, he later said, would shape his songwriting. When he was in his teens, and his parents had separated, his mother divulged the identity of his biological father: a professional gambler named Alexander Klegerman, who had been killed in a road accident. The 20-year-old Dolly was pregnant with her son when she married Jim Robertson in 1942.

From left: Van Morrison, Bob Dylan and Robertson in the finale of The Last Waltz. Photograph: United Artists/Getty Images

Guitar lessons from the age of nine led to his first electric instrument, a Christmas present when he was 13, and a year later he was playing in his first bands. His professional apprenticeship began at the age of 16, playing bars and clubs in Canada and the American south with the Hawks, the backing band for the extrovert American rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins. The Hawks had been joined by Helm, Danko, Manuel and an organist named Garth Hudson by the time Robertson played a memorably scorching lead part on Hawkins’s recording of Bo Diddley’s Who Do You Love?.

In 1964 the band left the singer to strike out on their own. The Stones That I Throw, a Robertson song released under the name Levon and the Hawks, had the beginnings of an original sound. But in 1966 it was Robertson who encouraged them to join Dylan on a tumultuous world tour that exposed them to the fury of fans enraged by the singer’s espousal of electric instruments.

After Dylan retreated to Woodstock, in rural upstate New York, Robertson and the others joined him to work on songs that became known as the Basement Tapes, plundering a variety of archaic idioms. Big Pink was the large wooden house in whose basement they rehearsed the 11 songs that became their own first album, four of them written by Robertson.

Its success, due as much to praise from such rock gods as Eric Clapton and George Harrison as to their record company’s advertising campaign, was followed in 1969 by a second album, recorded in Los Angeles, called simply The Band (and known to many, thanks to the sepia hue of its cover, as the brown album). The inclusion of such seemingly ageless and finely detailed Robertson songs as King Harvest (Has Surely Come) and The Unfaithful Servant convinced many that this was their masterpiece, while live performances underlined the qualities that set them apart.

But in a hint of the problems that would undermine the collective spirit, eight of the second album’s 12 songs were solely composed by Robertson. On Stage Fright (1970), there were seven, with eight on Cahoots (1971). On most of the other songs he was credited as a co-writer with Helm, Manuel or Danko. By the time a fifth studio album, Northern Lights – Southern Cross, was released in 1975, all 12 songs were written by Robertson alone. He was now earning far more than the others, which created distrust.

He could legitimately point out that his colleagues’ work ethic had been corroded by the temptations their success had made affordable, particularly after the move to California. By avoiding heroin, in particular, he remained productive. But after the mid-70s, in which a triumphant reunion tour with Dylan (and their appearance on his album Planet Waves) was followed by The Last Waltz, Helm’s bitter resentment over the way Robertson had handled their song-publishing affairs kept them apart. Manuel took his own life in 1986, Danko died of heart failure in 1999, and Robertson and Helm would not be reconciled until, according to Robertson’s account in his 2016 autobiography, Testimony, a meeting just before the drummer’s death from cancer in 2012.

Robertson’s last album, Sinematic, was released in 2019, the year in which his company produced Once Were Brothers, a documentary telling his side of the Band’s story. Before his death he was working on music for Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese’s forthcoming film about the struggle of the Osage Nation to retain control of the oil rights on their land in Oklahoma in the 1920s.

He is survived by his second wife, Janet Zuccarini, whom he married this year, by the two daughters, Alexandra and Delphine, and son, Sebastian, of his first marriage, in 1968, to Dominique Bourgeois, which ended in divorce, and by five grandchildren.

Robbie (Jaime Royal) Robertson, guitarist, songwriter, born 5 July 1943; died 9 August 2023