125 years later, is Dracula antisemitic — or is he just another vampire?

Stoker #Stoker

The silhouetted figure of the vampire Count Dracula, raises his cape in batlike-fashion, circa 1970. Photo by Getty Images

By Benjamin Ivry May 23, 2022

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the publication of Bram Stoker’s horror novel “Dracula” and the centenary of “Nosferatu,” the classic silent film inspired by it. Should Jewish readers kvell along with all the Transylvanian wannabes who adore everything vampirish?

The Tel Aviv Cinematheque is commemorating the anniversary of Stoker’s book with a special festival of vampire movies. As the Jerusalem Post cheerily announced earlier this month, the “celebration of all things bloodthirsty and undead runs until May 16.”

The cultural impact of “Dracula” in hundreds of films, TV adaptations, video games, animated cartoons, comic books and dramas, is undisputed. Yet in recent decades, academic researchers and bloggers have repeatedly published claims that antisemitism, itself often bloodthirsty and undead in today’s world, can be discerned in the pages of “Dracula.” Juxtaposing “Dracula” and Jews somehow seems incongruous, as the comedian Bill Hader showed on “Saturday Night Live” a few seasons ago, jocularly mentioning a Jewish Dracula named Sidney Applebaum.

As is often the case, readers and filmgoers see what they wish to see in any text or film. In “Nosferatu,” a manuscript page is fleetingly shown with mystical symbols on it, including a six-pointed star and what may possibly be a few Hebrew letters amid dozens of other signs.

Bela Lugosi prepares to bite the neck of an unconscious young woman in a still from director Tod Browning’s film, ‘Dracula’. Photo by Getty Images

Bela Lugosi prepares to bite the neck of an unconscious young woman in a still from director Tod Browning’s film, ‘Dracula’. Photo by Getty Images

In the 1931 Hollywood sound remake starring Bela Lugosi, the Count wears a six-pointed medallion of nobility, which some observers, including The Times of Israel and Jewish Currents, have insisted must be a Star of David.

This misapprehension was echoed in 1987, when General Mills was obliged to redesign cereal boxes for its Count Chocula breakfast food, as they contained a caricature of Dracula wearing the same six-pointed medallion, again decried by some Jewish media as a Star of David.

The context for this imagery was particularly fraught, because for centuries antisemites have employed the notorious blood libel to falsely accuse Jews of murdering Christian children to use their blood in the performance of religious rituals.

So it is understandable that critics are sensitive to any potential allusion to Jews in this blood-obsessed novel, especially since it was published at a time when an influx of East European Jewish emigration into the UK was also causing controversy. Count Dracula was, after all, the ultimate outsider, even if his aristocratic status separated him from 19th century Jewish refugees.

Essentially, discussions of antisemitism in “Dracula” rely on historical subtexts, since there are only two mild references to Jews in the novel of over 400 pages. Neither mention can be called complimentary, but popular literature in the UK well into the 1940s usually contained derogatory statements about Jews, Asians and other minority groups.

In terms of racism, Stoker was comparatively unemphatic. He is far nastier about Slovaks, termed “barbarian” with a theatrical metaphor: “On the stage, [Slovaks] would be set down at once as some old Oriental band of brigands.”

By contrast, trying to track down Dracula’s possessions, the protagonists discover that one item was received by Immanuel Hildesheim, a “Hebrew of rather the Adelphi Theatre type, with a nose like a sheep, and a fez.”

The theatrical reference was natural for Stoker, whose day job was as business manager for the celebrated Victorian actor Sir Henry Irving, whose performances at London’s Lyceum Theatre were widely acclaimed.

Irving’s roles included an unusually dignified Shylock in Shakespeare’s traditionally antisemitic “Merchant of Venice,” that reportedly later inspired the performance by Laurence Olivier in Jonathan Miller’s 1973 film version.

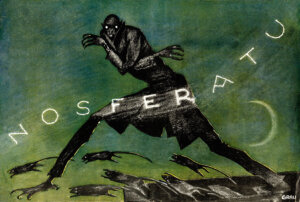

A poster for ‘Nosferatu;’ the 1922 silent German Expressionist horror film directed by F. W. Murnau. Photo by Getty Images

A poster for ‘Nosferatu;’ the 1922 silent German Expressionist horror film directed by F. W. Murnau. Photo by Getty Images

By contrast, Irving’s rival theaters, such as the Adelphi, were known for bloodcurdling melodramas and actors playing caricatures. This type of exaggeration seen at a vulgar house of entertainment is cited to evoke Immanuel Hildesheim’s appearance, like an unsubtle stage image of a Jew.

The nasal insult was clearly intended to mean that his proboscis was like the snout of a sheep, rather than resembling an entire sheep. Noses are another sensitive point for readers today, due to still another misleading stereotype involving Jews. Stoker describes Dracula’s own nose as “aquiline,” meaning with a prominent bridge that makes it look curved or slightly bent.

Yet Sherlock Holmes, a contemporaneous hero of popular literature, was likewise given an aquiline nose by his creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, without any hint of Yiddishkeit.

Stoker’s cryptic characterization, citing a theater of dubious artistic integrity, is an example of semi-humorous japes interwoven as slight comic relief in the thrilling narrative. As one reviewer of the original novel pointed out in Vanity Fair in 1897, although “Dracula” was terrifying, it also contained bits of comic deflation, such as the detail that the murderous vampire could be warded off by using garlic.

This intermittent lightness might be part of the second and final direct mention in the novel of anything associated with Judaism. After the vampire has shipped 50 boxes of ordinary soil to London, one of the transporters is asked about the cargo and notes in a working class accent: “… There was dust that thick in the place you might have slep’ on it without ‘urtin’ of yer bones; an’ the place was that neglected that yer might ‘ave smelled ole Jerusalem in it.”

The Jewish literary historian J. Jack Halberstam, in a detailed indictment of Stoker’s prose, commented: “The worker is quite specific: to him the smell is a Jewish smell. Like the diseases attributed to the Jews as a race, bodily odors, people assumed, clung to them and marked them out as different and indeed repugnant objects of pollution.”

It may also be that Stoker’s workman was likening the odor to ancient dusty aromas of old Jerusalem during Ottoman rule, as described in turn-of-the-century accounts of pilgrimages, typically unenthused about sanitary conditions.

Max Schreck starred as the vampire Count Orlok in ‘Nosferatu.’ Image by

Max Schreck starred as the vampire Count Orlok in ‘Nosferatu.’ Image by

Some literary critics delve into the all-too-common insult of calling enemies vampires, regularly applied in worldwide conflicts to a variety of opposing forces. With quasi-masochistic certainty, they conclude that Stoker must have been referring to Jews. Yet the author Hall Caine, a friend of Stoker’s, penned an obituary claiming that Stoker’s fiction had only one purpose: “to sell,” with “no higher aims,” and no other ideology.

Pot-boilers, created to generate cash, may contain implicit or explicit antisemitic messaging. Yet so much of the messaging that has been perceived in “Dracula” amounts to subtext, until one wonders if some well-intentioned Jewish readers may have overdone the self-flagellation. After all, there are far more plainly stated antisemitic slurs in English literature. There’s even a documented tradition of overtly Jewish female vampires, Estries, mentioned in the “Sefer Hasidim” by Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg, a twelfth century German Jewish mystic.

Perhaps one day, readers may see the notion of Dracula as a subliminal Jewish baddie as outdated, like previous suppositions that Stoker’s malefactor was inspired by the historical Vlad Drăculea, known as Vlad the Impaler, or by another historical figure, Elizabeth Báthory, a Hungarian noblewoman, accused mass murderer and vampire.

Most critics dismiss such concepts today, so the current fashion for spotting unspoken references to Jews throughout “Dracula” may likewise fade with time, unless it turns out to be as immortal as the vampire himself.