Can Morrison cash any pandemic, or economic recovery cheques?

Morrison #Morrison

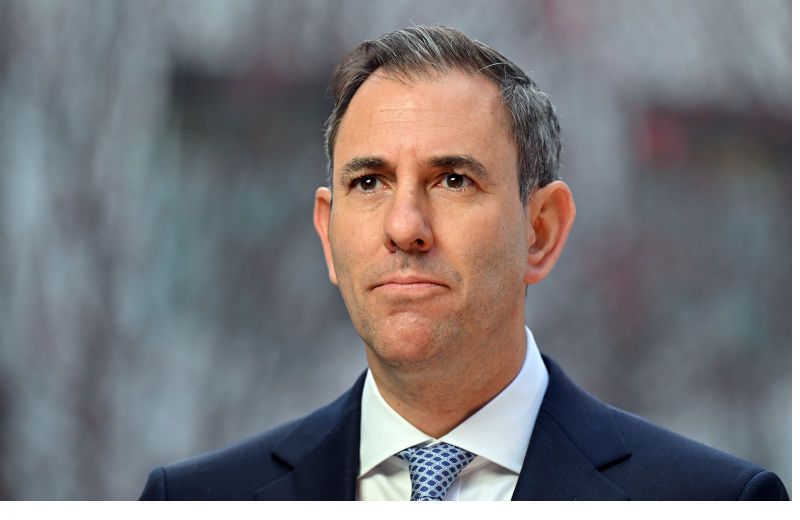

Shadow Treasurer Jim Chalmers has had the measure of both Frydenberg and Morrison on economic issues. Image: AAP

Once Morrison was in an advantageous position to exploit Australia’s apparently successful management of the coronavirus pandemic and the economic shutdown it involved. He lost much of his advantage by his conflicts with the states over pandemic management, local responses and his determination to restart the economy before the pandemic was under control, as well as by a host of failures over vaccine ordering and distribution.

Even his economic measures, including Jobkeeper and the taking on of debt and deficit – an amazing turn-around from among economic ideologues – seem to have ceased to work for him as pluses. It ceased to work because debates have resumed over accumulating debt and deficit. And rising interest rates have dampened confidence in the recovery.

Morrison’s problem is in re-inventing and re-marketing his achievements, but he has left it too late. From his point of view, however, it could be a more positive tale than a recitation of his achievements over reducing emissions, promoting electric cars, building girls’ lavatories and changing rooms at sporting ovals, and changing the equations over violence against women and sexual harassment at parliament house.

Morrison’s celebrated marketing nous is not working for him. He has a major credibility gap. The key to the Morrison style lies in his capacity to thoroughly believe anything he is saying now, even as it is plainly, the opposite of what he said yesterday – a fact he will indignantly deny. In time, however, his prevarication, and what Barnaby Joyce has called his capacity to reconstruct facts, has become obvious. Even as he faces a mainstream media far less critical of him than I have ever observed of any prime minister in recent history, his capacity to bluster, to make it up, or to deny the truth is declining. At this stage most of his well-rehearsed lines are failing, and his awful run of luck continues to dog him. Attempts to artificially ramp up some issues – conflict with China for example – also threaten to revive memories of his great capacity to crisis management, as manifest with bushfires and floods.

Chalmers has neutralised Morrison and Frydenberg’s claims to economic nous.

Shadow Treasurer Jim Chalmers has had the measure of both Frydenberg and Morrison on economic issues. He has more than made up for the poor impressions caused by Albanese’s alleged “gaffes” of failing to remember statistics. I doubt that such “gotcha” moments have long-term effect, even as they underline the combativeness of most of the mainstream press, including some ABC and Nine (Fairfax) journalists. Yet Albanese needs a better way of responding than looking like a deer in the headlights.

For Morrison, it shows Albanese as skimpy on detail, and not experienced enough in economic management. But if by contrast he is a master of detail, it underlines his tendency to micro-manage his ministers. And it also draws attention to the key Morrison problem: not his command of the facts, but his judgment in applying them to the problem at hand. And his failures to follow through after making announcements.

Albanese had shadow ministers whose job is to be masters, or mistresses, of the detail within their portfolio areas. As ringmaster, he is supposed to know what is going on, but not necessarily to the point of understanding each bit of arithmetic or every dot-point. His team is able – on the face of it more competent than the Morrison team, which is overfull of factional, religious and personal mates.

And complete liabilities Morrison refuses to dump for fear of giving a win to the opposition. Some of these should be terrified about the prospect of a national integrity commission. Albanese’s team has rehearsed what would happen if the leader caught Covid (as Malcolm Fraser did, with measles, in 1977).

By contrast, some of Morrison’s more useful ministers – such as Frydenberg and Peter Dutton – are focused on their own survival, and others, apparently recognised as the liabilities they have always been, are being kept well out of the spotlight. Morrison has extraordinarily little to sell, and he himself is not regarded as an electoral asset in many electorates, particularly, as it turns out, in the inner-city ones where the Teal Independents have put incumbents under such pressure.

The last thing that Albanese should be doing is cruising confidently to victory. If the polls suggest that he is comfortably ahead, he should be redoubling his efforts to confirm the good impressions and to deal with the perception of limited and narrow vision, a meanness of perspective and a refusal to take chances. He should also be alert for a ruthless enemy attempting to regroup, who will throw everything at him before the contest is over. And not necessarily by Marquess of Queensberry rules.

Leaving aside the caretaker rules, Morrison may have as little as 16 days of power left. While there is mud on the floor, arrows in his quiver, public dollars in his purse, he will fight on. He may even win, or so handicap, or booby-trap, his successor, that the change of power changes nothing very much. It could be Morrison’s greatest legacy that his defeat produced a government so timid and unadventurous, so committed by self-denying promises, so contaminated by the new traditions of government by discretion, that it was hardly worth the effort.