After 30 Years, Shelley Novak Learns When to Leave the Party

Shelly #Shelly

click to enlarge

After three decades, Shelley Novak says goodbye to South Beach.

On a Saturday night in February 2020, two black Payless heels trail onto a short stage at Las Rosas. From them sprout a chiseled set of unshaven calves concealed beneath an electric-blue, floor-length dress.

Shelley Novak may stand only 5-foot-4 with a stocky physique she likens to Barney Rubble, but her calves are statuesque. To the 55-year-old, they are her prized possessions — hard-won trophies from three decades of performances in platforms and pumps. She would have shown them off to her audience at the Allapattah bar had she not planned for a formal outfit. At Las Rosas, her signature feathered blond wig, fake mole, icy-blue eyeshadow, and bright-crimson lipstick are paired with an embroidered cream cardigan atop her glittering gown. A mat of black chest hair sprouts from a small cutout on her breastbone.

A crowd has gathered for the 27th annual Shelley Novak Awards. Everyone came to hear brazen award acceptance speeches from established and up-and-coming queer artists, but they will stay for Shelley.

The self-proclaimed outcast has never conformed to beauty standards — not even in a community that pushes the boundaries of expression. While the mainstream drag world remained hyperfeminized when she rose to local renown in the early 1990s, Shelley stood out as fearlessly gender-bending (mostly owing to her resentment of shaving).

Related Stories I support

Local

Community

Journalism

Support the independent voice of Miami and help keep the future of New Times free.

She’s hairy. Her voice is husky. Her jokes are bold as brass. She proudly advertises her “fuck you, pay me” attitude and insatiable desire to stand under the spotlight. A five o’clock shadow usually peeks out from underneath her foundation, and her makeup routine has stayed the same since 1992. The grit she embodies is contagious. What more traditional drag performers once called a mockery of the art form is now what emboldens incoming queens.

“She was who I was — just in the ‘90s,” drag performer Karla Croqueta tells New Times. “I started going out and partying with a hairy chest and a beard. And Shelly was like, ‘I used to do something similar and people just used to fucking yell at me all the time.’ We’re on the same side of the fence.”

As Shelley stands at the dive bar dressed as what she describes as “the Madeleine Albright of drag,” she grabs hold of the microphone. Stage lights blaze to life in a fierce flash of red, then dim. In true fashion, Shelley opens by belting Ethel Merman’s “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

Like everything Shelley does, it seizes and holds her audience’s attention.

click to enlarge

In June, Tommy Strangie packed up his South Beach apartment and moved north to Florida’s Space Coast.

Photo by Natalia Galicza

The Short Goodbye On an afternoon in June, Tommy Strangie is packing his Miami Beach apartment into boxes. Action figures, comic books, fashion books, and disposable photos all sit in organized piles. Of the items relegated to the donation bin are secondhand dresses with storied pasts — and a familiar pair of Payless pumps.

A Billabong T-shirt and Bermuda shorts take the place of a gown. Sans wig and heels, Strangie’s missing a few inches, and without the painted black brows, his face softens.

Strangie admits that he has contemplated retiring from his second life as Shelley Novak for years. Several instances have nearly pushed him over the brink, from the nightlife slump that followed the 1997 murder of Gianni Versace to his Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis in 2013. But each time he tried to leave, he felt called to come back.

Still, if surviving a generation of designer drugs and dancing at discotheques has taught him one lesson, it’s that you have to know when to leave the party.

“Miami Beach is a place where I belonged,” he says. “It’s a city where I never needed a car, where I could walk to my gigs or whatever bar I needed to go to. But now it’s just becoming a little too much for me. And it’s not the city; it’s not the people. It’s because I’m looking through the eyes of an older person.”

Since the dawn of Shelley Novak, Miami’s drag community has expanded. Performers in full beards and body hair, though they still face hostility, are easier to find. From Queef Latina to Karla Croqueta, performers care less about morphing into a conventional archetype of femininity and more about creating a new character altogether.

He’s proud to have helped pioneer the city’s current drag scene, but Strangie stumbled into his first gig entirely by accident. Amid the ruckus of the early ‘90s, when models, celebrities, and drug peddlers all laid claim to being kings of Miami, a queen was born.

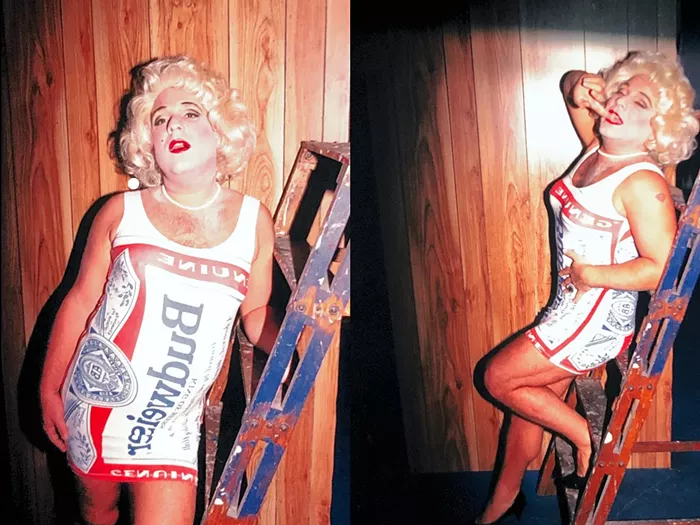

click to enlarge

Shelley was discovered in 1992 when she danced on the flat top of a sound system while scarfing down pizza.

Photo courtesy of Dezi

Accidental Drag In October 1992, Tommy Strangie made a hasty decision to ditch the freezing climate of his hometown of Everett, Massachusetts, just north of Boston, for sunny Miami Beach. He’d broken up with his boyfriend a few months prior and could not fathom what shape his future would take. He needed a new home, a new job, and someone new to make out with.

One evening while lamenting the dissolution of his relationship in a phone conversation with an old friend, he caught wind of promising news: Three familiar faces from Everett had moved into an apartment building that was Miami Beach’s version of Melrose Place, and Strangie was invited to join them.

His mother already had the pleasure of listening to him sing Carol Burnett and Barbra Streisand into a hairbrush from a young age. She supported the idea of Strangie branching out — though she didn’t know he was gay or open to the idea of doing drag. What she did know was that he was a natural-born entertainer, and perhaps it was time for him to entertain elsewhere.

By the week of Halloween, Strangie had settled in South Beach. The 17-block island oasis immediately proved itself the polar opposite to chilly Everett. The rent was far cheaper (just a tad over $300 a month), the gay community far larger.

Also, no one donned a puffy jacket. Kate Moss-like models were in every coffee shop. Art deco homes were painted in pastel hues. Drag queens were saluted as they strutted down sidewalks, and gay clubs were strewn throughout the city like a massive constellation, one that Strangie observed in awe.

“When I was in the Boston area, it did not embrace the misfits. Then I came to Miami, and it was like when Dorothy opened up the door after the house dropped and she went from sepia tone into Technicolor,” he recounts. “And the yellow-brick road with the overgrown set of Munchkins was all gays in short-shorts.”

What Strangie marveled at — a city that had blossomed into the gay mecca of the ‘90s, and the palpable urgency of its drag performers — was a culmination of decades’ worth of queer resistance.

LGBTQ+ advocates organized what is considered Miami’s first Pride Week in 1972. The unabashed celebration of queer existence struck back against policies that stifled diverse gender expressions and sexualities. It felt even more imperative to continue commemorating queer life in the ‘80s, as the HIV/AIDS epidemic hit the city in full force. The desire for the LGBTQ+ community to rise anew from the ashes of the ‘80s led to Miami’s bacchanalian spirit of the ‘90s. Strangie found himself at the head of the banquet table.

There was no better city to whip out the drag costume Strangie had assembled back in Massachusetts: a sequined, seafoam-green dress with matching heels — “The kind your grandmother would wear on Easter” — and a blond wig.

The name to accompany the clothing, Shelley Novak, was an amalgamation of Shelley Winters and Kim Novak.

“[Miami] was like when Dorothy opened up the door after the house dropped and she went from sepia tone into Technicolor.”

A few weeks after arriving in Miami, Shelley made her South Beach debut at the Winter Haven Hotel’s Halloween tea dance. She was nudged onto the flat top of a booming sound system, where she danced in her Mentos-colored ensemble while scarfing down pizza.

Unsurprisingly, she attracted attention.

Slice still in hand, Shelley was approached by DJ Mark Leventhal, who asked her to return to the Winter Haven the following week for a paid gig. Shelley would earn $200 to liven the party — a service she would have provided for free. The pay was more than double Strangie’s paycheck at the time. More than that, the chance to earn a living by expressing the traits society had previously attempted to suppress felt like an opportunity for liberation.

Strangie had grown up an only child, and even though his parents were oblivious to his sexuality, bullies in primary school had sniffed it out to use as ammunition for insults. He felt lonely, but he had a line of defense: making people laugh. Humor is what made everyone gravitate toward Shelley.

The ‘90s in Miami marked a period when the rich and famous searched for drag performers to hire as entertainers for their private parties. Gigs were abundant and lucrative.

In 1993, Shelley debuted the Shelley Novak Awards, which spotlighted local drag artists — something no one else in Miami had yet attempted. It connected her with her community. She networked with well-known queens, showcased and mentored newcomers, and continued to get her jollies through hosting and performing.

More people learned Shelley’s name. More jobs rolled in. She got to meet Robin Williams, who sought her out to learn about Miami drag for his role opposite Nathan Lane in The Birdcage, which was filmed on Ocean Drive. She found herself in a lengthy conversation about cake with George Harrison at a party thrown by a Brazilian NASCAR driver.

All Strangie’s life, he’d wanted to feel seen. As Shelley, he felt he belonged no matter where he went or to whom he spoke. When she talked, people listened.

The more Strangie experienced drag — the lightheartedness, the grit, the testament to individuality — the more he longed to embody and protect it.

Then, in 1997, Gianni Versace was found murdered in his mansion. The death of the fashion designer sent the herds of Miami models flocking elsewhere, taking the rock stars and millionaires with them.

The assassination of the gay icon also triggered a momentary lull in queer nightlife, as the community was left to question its safety. Some fled north to queer-friendly Wilton Manors. Some considered the finale of the ‘90s as a signal to slow their pace and move to a less pulsating locale. Others simply followed those who departed en masse in search of a new city with a new set of thrills.

But Shelley was just getting started.

click to enlarge

Much of the period between 2000 and 2007 has been erased from Shelley’s memory.

Photo courtesy of Dezi

Nightlife in Decline Kremlin. Paragon. Warsaw Ballroom. West End. The beloved ‘90s gay clubs that connected South Beach into a constellation slowly burned out. Rising rents and commercialism ushered in their demise.

In drag, an industry founded on a gig economy, queens must follow the money. If a steady stream of jobs isn’t to be found in this city, they vanish to another just as quickly as they appeared.

But Shelly had made a name for herself in South Beach. She did not plan to let it be forgotten, nor did she intend to move in order to preserve it. When the new millennium kickstarted the rise of social media, she resolved to casting her first digital footprint.

In 2006, one year after Facebook and YouTube came into being, she hosted a radio series with a childhood friend from Everett. The pirate radio program, Kenneth’s Freakquency, was a talk show Shelley describes as Howard Stern-esque. She had her own segment, during which she could be as nonsensical as she wished.

Shelley never thought to continue honing her digital presence; her heart resides in the intimacy of an in-person venue. Nothing beat the rush of watching shock unfurl in another’s eyes, widened in response to her absurdism.

Nothing except Ecstasy.

Much of the period between 2000 and 2007 has been erased from Shelley’s memory. She tells New Times that she once calculated how much Ecstasy she’d ingested over the span of seven years. She tallied it up at 18,000 pills.

The drug led Shelley to throw up on Ricky Martin’s shoes at Crobar. It also led her to begin dealing drugs for a Cuban crime family. She became partial to marijuana in 2007 after the Miami Beach Police Department raided her home: An acquaintance of the crime family had been found wrapped in plastic and floating naked in the Everglades, the corpse bloated by the heat and marsh.

The news was sobering. Life, Shelley realized, is fragile.

“I just wanted to give a voice to a lot of the queens that don’t have a voice. Some of these young queens are working for drink tickets.”

With a fresh perspective, she pondered the city’s changing infrastructure, which in turn made her rethink the trajectory of her career. She was duly convinced that she’d retire in 2008. She struggled to select nominations for her eponymous awards show, crediting the difficulty to feeling that she’d aged out of the scene. Money grew thin, as gigs became fewer and farther between.

At the end of the 2000s, though, something shifted. RuPaul’s Drag Race debuted in 2009. The reality show mainstreamed drag culture by blasting it on television. Once viewers were offered the chance to view the art form as a respected trade rather than a running joke, an increase in the number of budding artists followed.

The influx of fresh faces, whether shaven or not, reignited Shelley’s mission to assist newcomers in drag. She no longer felt tasked with just her own career but with aiding the evolution of an industry. Drag culture has always revolved around the creation of chosen families and the formation of communities among outcasts. Shelley wanted to give back what she’d been given: a trustworthy team of supporters and an encouraging push in the right direction.

“I just wanted to give a voice to a lot of the queens that don’t have a voice. Some of these young queens are working for drink tickets. So I’ll give them an opportunity to get out there and speak their mind, say what they have to say. It can be so moving. I will nominate everybody in town. And if you’re not nominated, I will make you a presenter so no one’s left out.”

The same year Drag Race first aired, Miami Beach Pride became a city-sanctioned annual event. Now an official festivity, Pride brought a rush of LGBTQ+ faces back to South Beach, helping to compensate for those who’d fled at the end of the millennium.

Shelley excitedly looked toward the future once more — until she found a lump in her neck.

click to enlarge

Shelley with Juleisy and Karla Croqueta in 2015.

Photo by Chris Carter

The Prophecy At the onset of the 2010s, everything seemed to be going wrong. As soon as Shelley had found her footing, life threw a vaudeville hook to yank her off-balance.

South Beach’s status as the focal point for the area’s nightlife began to slip. Across the causeway, Wynwood, with its kaleidoscopic murals adorning nearly every square inch of stucco, was generating a lot of buzz. Partygoers swarmed the burgeoning neighborhood and the nearby downtown area.

Consequently, it became difficult for Shelley to land a gig in South Beach. She didn’t own a car and didn’t adore the idea of taking public transit all the way into Wynwood.

One of the last-standing gay clubs in South Beach, the Palace, still brought in drag performers regularly. Those performers were typically young, with extravagant clothing and bold choreographies.

Shelley admired them, but she couldn’t relate. Never one to fret over appearing perfect or polished, she kept her attire simple, with outfits purchased at Ross Dress for Less or Goodwill or supplied by friends proffering hand-me-downs. She also did not dance often. Her calves may look like they’re etched from stone, but they’re not built for much beyond strutting and stomping.

“I mean, if I ever do a death drop, truly call 911 because I probably have died,” she says.

Since there weren’t enough opportunities for her to feel stable in South Beach, she again resolved to retire, announcing her leave just two years after her last false alarm.

Because her scruffy-chic appearance makes her more of an outlier, Shelley’s friends in California told her she’d make it big in Los Angeles. People embraced the oddities there, they assured her. So with speed and impulsivity, Shelley moved to L.A. in 2011.

Starting fresh meant she would not initially be offered the privileges to which she’d grown accustomed. Drinks were no longer free, and she wasn’t allowed to bypass the velvet ropes. Shelley may be a performer of the people, but she’s not keen on paying for her own cocktails or wasting any amount of her precious time in line.

She lasted one year before she came back to Miami.

Her 2012 South Beach comeback coincided with the ancient Mayan prophecy that predicted the world would be destroyed at the close of that year. Shelley, of course, thought it was complete bullshit.

Then Strangie remembered the lump in his neck that he’d ignored, which grew from one mass to two without his noticing. Just to be safe, he got them checked out.

The lumps were Hodgkin lymphoma. Strangie instantly suspected the years of Ecstasy.

He didn’t want to think too much or stress about it, so he handled the diagnosis the best way he knew how: by having sex with strippers and getting belligerently drunk. One night, while availing himself of just such a therapeutic rendezvous, Strangie mentioned the cancer to his conquest. The stripper started crying.

“I had a friend who had cancer, and he ignored it. And he died, and I don’t want you to die,” they told Strangie between strangled sobs.

It was a mood killer, but it was also a wake-up call. Strangie concluded that he would decamp to Everett to pursue treatment.

At Massachusetts General Hospital, Strangie found out that his cancer fit the criteria for a study that was being conducted at Harvard University. He had the opportunity to try out a then-experimental drug, brentuximab vedotin, at no cost. It didn’t make him anxious that the drug was unproven. It was better than sitting around and doing nothing.

After two infusions, Strangie was clear of cancer. Eight months of chemo followed. He lost every last hair on his Italian-American body. The thick, black carpet that graced his décolletage disappeared for a year. A small price to pay for being cancer-free, but bittersweet nonetheless.

When he finally made it back to Miami, he found a new legion of drag queens who looked more like Shelley, body hair and all.

“There are many things a woman can look like and be, and I really think that Shelley gave a platform to myself and other newcomers to show that.”

Ironically, Shelley was still almost entirely hairless. But she didn’t care. She’d hoped the incoming generation of young drag artists would be able to experience a generation of greater range and inclusivity in their lifetimes than she had in hers.

Queef Latina’s beard is not only dark brown and thick but lengthy. It juts out in a curtain of straight strands that add a few elongated inches to her heavily contoured face.

Karla Croqueta, a nonbinary performer who likewise centers their style on being bewhiskered, has a dark thatch of a beard and a black blanket of fuzz on their chest — regularly shown off from beneath a cropped, sleeveless, or low-cut plunging top.

Where drag performers once played it safe and aimed to blend in, the modern goal is to stand out and break the mold.

And the new performers revere Shelley — an unsinkable force of nature who carved out a space for the less-than-traditional artists long before it was in style to do so.

“There’s been a lot of resistance from the more pageant-style drag queens,” Karla says. “But there are many things a woman can look like and be, and I really think that Shelley gave a platform to myself and other newcomers to show that.”

Double Stubble, Counter Corner, Wigwood; more events popped up that aimed to celebrate the fact that the new cavalry of drag queens aren’t all of a single caliber. There’s nuance, complexity (albeit gigs are still geographically concentrated in Wynwood and downtown). Shelley wondered about the fate of her precious South Beach, whether it would ever return to the gayborhood it once was.

She remained loyal to South Beach for the Shelley Novak Awards for as long as she could, but even she shifted her sights elsewhere. The two most recent shows, in 2019 and 2020, took place on the other side of the causeway, at Gramps and Las Rosas.

Nothing and no one can force the curtains closed on Shelley Novak. But now that her work is complete, her dearest goals accomplished, she might be ready.

click to enlarge

The past three decades have been challenging and life-changing for Strangie

Photo by Natalia Galicza

Life After Shelley Strangie describes the décor of his South Beach apartment as “what you would find in the alley.” It’s hodgepodge and miscellaneous, with stolen bar stools and splotches of unmatched prints and colors. He had to get rid of it all. In June, he watched a young family move into the unit above him. They had one suitcase of belongings and a baby. Strangie decided to give the bright-eyed parents everything: his couch, his bed, the seven loaves of Trader Joe’s focaccia in his freezer. Where he was going, he wouldn’t need it.

The past three decades have been challenging and life-changing. Strangie cherishes the lessons he has learned in the glamorous city whose siren call beckoned him back no fewer than three times. This goodbye, he promises, will be the last.

Despite having previously acted as a battery pack of pure, unbridled energy, Strangie felt ready to unplug, to settle somewhere more serene.

“I got all of my ya-yas out with Shelley Novak, but you can’t keep doing it,” he says. “A top looks amazing while it’s spinning, but at some point, the top has to roll over on its side. It can’t keep spinning forever.”

Shelley Novak had become one of few drag stars to stay in Miami for nearly a lifetime and reinvigorate the scene with such fervor. But with Strangie’s move north to Florida’s Space Coast, Shelley would be put to rest. The wig would be traded in for a bucket hat, under which Strangie would tuck his tanned face.

His house is on the beach, temporarily filled with wicker and rattan furnishings. He falls asleep to the sounds of crashing waves instead of drunkenly crying clubbers and sex on his front steps. On his to-do list: writing a book that tells the Shelley saga.

It feels refreshing to Strangie — to blend in after a career of flaunting Shelley in others’ faces. He can relax while doing so because he knows what he has left behind: a scene that grows more shocking and sanguine as the seconds pass, and a generation of queens who proudly carry it forward on their shoulders.

“The kids have so much freedom nowadays, and I’m so glad they’re taking advantage of it. They’re making the scene better for the next generation that’s coming up so that one day, everything is just going to be normal,” he proclaims. “What I hope for the future is that we get right back out there and into people’s faces — that these kids keep pushing the envelope to make things more and more punk-rock, and less and less safe.”