History of Gainsborough Old Hall

English Heritage #EnglishHeritage

Gainsborough Old Hall is a medieval manor house in Lincolnshire, the surviving structures having been built by Sir Thomas Burgh II in the late 15th century. The hall was the seat of the Burghs from 1430 until 1596, and then sold to the merchant Hickman family, who resided there until around 1730.

Over the next two centuries the building was leased for various purposes – a fascinating mix of residential use, workshops and businesses, a theatre space and civic institutions. Throughout it has been intimately connected to the town of Gainsborough.

The great hall at Gainsborough, built by Thomas Burgh II, retains its original medieval timber ceiling

Burgh’s new hall

Thomas Burgh II (c.1430–1496) inherited the manor of Gainsborough in 1455 from his mother – his father had died shortly after his birth. Over the next two decades, he began rebuilding works on the estate. Archaeological investigations indicate there were earlier structures on the same site, but there is no evidence as to the date of those buildings.

Thomas’s works included the rebuilding of the main hall range, with the central great hall at ground level flanked by two-storey wings at each end. At the same time a long east range was raised at right angles providing extended private apartments.

Tree-ring dating conducted in the 1980s indicates building likely began in the later 1460s, perhaps reflecting Thomas’s knighthood in 1461 and his growing status at court. But it is also possible that it began in the early 1470s following an attack on his estates by men loyal to Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, where forces ‘pulled down his place, and took all his goods and chattels that they might find’.

Towards the end of the 1470s work was begun on a three-storey lodging range, erected on the footprint of the earlier west range. The next decade saw the addition of a fashionable brick tower at the north-east corner, and a vast new brick kitchen. These have been seen as discrete phases of work, but it may be more accurate to understand them as a single prolonged campaign to realise Sir Thomas’s ambitions for the manor.

Sir Thomas Burgh’s coat of arms, painted on a brass plate on the stalls reserved for Knights of the Garter in St George’s Chapel, Windsor © Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Sir Thomas Burgh II

Thomas was an agile and effective servant to four kings. He was adept at shifting his allegiance at critical points and maintained a trusted relationship with first Edward IV and later Henry VII. In around 1463 he married Margaret Ros (c.1425–1488), whose aristocratic heritage and independent wealth brought him a new level of status and respect. In 1487 Thomas was made 1st Lord Burgh by Henry VII, the culmination of an assiduously managed career that placed the Burgh name firmly on the national stage.

Thomas’s will provides some sense of his character and preferences. It is clear he held great affection for his wife, Margaret, and was generous towards, if watchful over, his four children. He appears to have held his servants and household staff at all levels in regard.

Thomas comes across as a man of clear intent, who thrived on detail – a hands-on administrator who probably paid close attention to the design and construction of the new buildings at Gainsborough. He was also a pious man, making bequests to nunneries and friaries, and leaving funds to establish a chantry chapel in All Saints Church, in the village of Gainsborough, for a priest to say a daily mass for his soul.

Portrait of Henry VIII based on a work from around 1542. Gainsborough Old Hall had two royal visits – one from Richard III in 1484 when Thomas Burgh II was lord of the manor, and another from Henry VIII with his fifth wife, Catherine Howard, in 1541 when Thomas III was the owner © National Portrait Gallery, London

The Later Burghs

When Thomas died in 1496, the estate was inherited by his eldest son, Edward (1464–1528). Despite careful preparations put in place by Thomas, Edward failed to forge the same degree of close personal relationship with Henry VII as his father had.

Edward soon found himself in debt to Henry and subject to suspicions of involvement in plots against the king. He was imprisoned in 1497, and in 1510 declared insane – ‘distracted of memorie’. After Edward’s death, his son Thomas III (c.1480–1550) inherited the hall at Gainsborough.

Thomas III was married to Agnes Tyrwhitt, daughter of a prominent local knight, Sir William Tyrwhitt, giving him useful contacts as he shored up the Burgh name in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

By 1540 Thomas seems to have moved the household to Euston in Suffolk, the seat of his second wife. Though Henry VIII stayed at the hall in 1541 with Catherine Howard, Gainsborough was no longer the centre of Burgh affairs.

William Hickman’s changes to the hall mainly focused on the east range, shown here, including encasing much of the structure in brick

New Ownership

Thomas III’s son William (1522–84) also lived away from Gainsborough and focused his attentions on his southern estates. Thomas IV (1558–97), William’s son, also seems to have given little attention to the estate, though the fine newel stair and gallery added to the southern face of the great hall may date to his ownership. Increasingly saddled by debt, and with complaints that his estate was in disarray, Thomas IV was forced to sell a number of holdings.

Gainsborough was sold to William Hickman (1549–1625), a London merchant, who moved in with his first wife, Agnes, and his mother, Rose, in 1596. Agnes died childless three years later, but William was quickly remarried to Elizabeth Willoughby, 32 years his junior and with whom he had four children.

William and Elizabeth invested in the hall, fashioning a more modern and serviceable family residence. They focused on the east range, creating a suite of rooms at its south end and encasing much of the structure in brick, with wide windows and new fireplaces. Inside, their tastes were displayed through fashionable oak panelling and painted walls with intricate foliage patterns, tapestries and other fine fabrics, rich furniture and jewelled ornament.

Detail of a portrait of Sir William Hickman from 1596, when he moved into Gainsborough Old Hall © Private Collection

Faith and Business

William Hickman adopted the fervent Protestant faith of his parents, Rose and Anthony, who had sheltered radicals persecuted during the reign of Queen Mary, before fleeing with their young son to Antwerp. Fifty years later William appears to have been supportive of local preachers at odds with the established Church, possibly aiding members of a local Separatist congregation before the pressure for him to desist became too great.

William was also an astute and ruthless businessman, asserting his rights as the owner of the manor and manipulating his authority to maximise both his control and income. He was not a popular man, being called a ‘threadbare fellow’ by one complainant. William persisted, enclosing areas of common land, contesting local market rights, levying tolls on river goods and seeking to open up the Gainsborough market to traders from London.

His tactics, continued under his son Willoughby (1604–49), are estimated to have helped increase income from tolls alone from £10 per annum, under the last Lord Burgh, to near £250 in 1640.

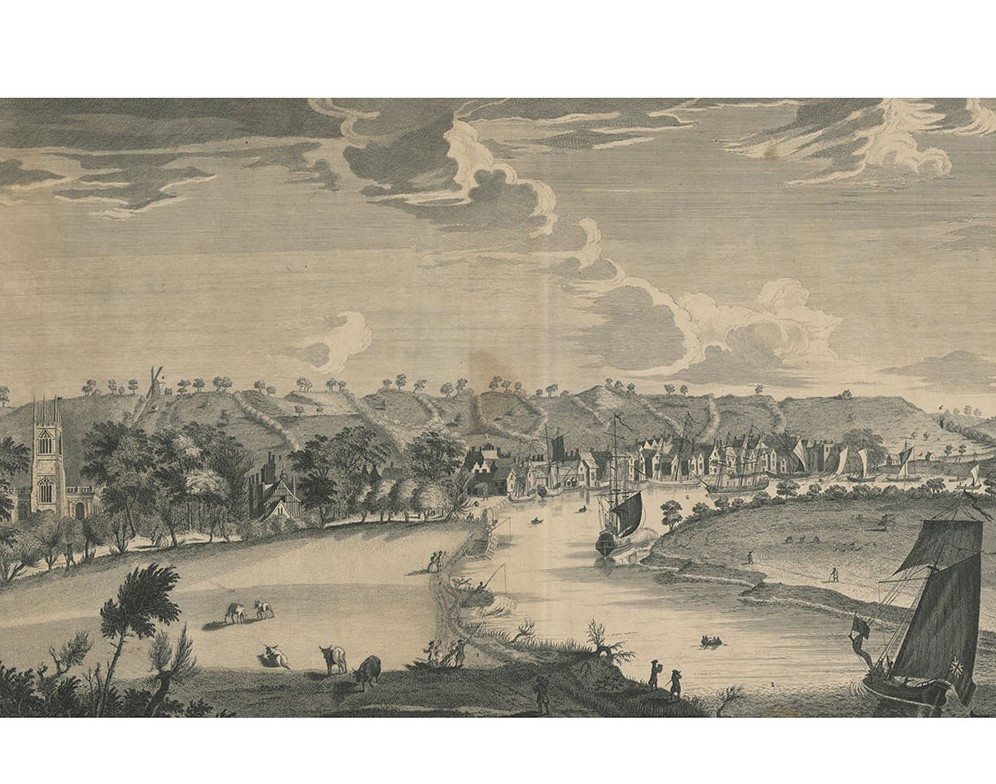

A view of the town of Gainsborough from the north-west from 1747. All Saints Church is seen in the middle distance (far left) with the Old Hall to its right © The British Library

A New Role

During the Civil Wars (1642–51), Willoughby Hickman kept a low profile, managing to be made baronet by Charles I in 1643 whilst also retaining his estates under the emerging Commonwealth. Willoughby’s heirs, his son William (1628–82) and grandson Willoughby (1659–1720), established roles as Justices of the Peace, Commissioners and MPs, and were important regional players.

Sir Neville Hickman (1701–33), the great-great-grandson of the first William Hickman, inherited in 1720. By around 1730 he had moved the family out to nearby Thonock Hall, leaving the now Old Hall to an uncertain future. Across the next two centuries the hall ceased to act as a unified building, the various structures being adapted to different uses that would change over time.

The east range was leased in 1733 to Willoughby Bertie, the future 3rd Earl of Abingdon. A century later the principal rooms of the range were reported to be in use as the workshop of Samuel Spray, a machine maker.

A drawing of Gainsborough Old Hall from the north-west in 1835, by J Rhodes Dell

Across the courtyard the lodging range was converted into a coarse linen factory by local businessman William Hornby. While that initiative was unsuccessful, a raft of other enterprises occupied the ground floor of the range and its outbuildings into the later 19th century. The upper floors of the range were converted into tenements, serviced with a row of wash houses above the drain and where a single room supported an entire family.

As Thomas Miler wrote in Our Old Town in 1857:

It had been let off for a long time in separate rooms for shops and dwelling places, to the great disgrace of the owner, for it was one of the finest old baronial mansions that could be found within many miles of this old-fashioned town. But excepting the walls and a few architectural ornaments, both within and without, there was but little left to proclaim its former grandeur beyond its massiveness and the immense space of ground it covered. You peeped in and saw its great ground floor apartments occupied by joiners, and coopers, and bricklayers – depositories of lime, hair, and bricks – and you turned away disgusted.

The Old Hall pictured in 1803 from the south, facing into the courtyard. The theatre stair (left) led to the gallery level on the west side of the great hall

Preaching and Performance

While the two side ranges of Gainsborough took on a multi-occupancy, multi-functional role, the great hall continued as a place of gathering, occasion and performance. John Wesley (1703–91) preached in the chamber and the yard outside on a number of occasions through to the 1780s. He recorded his first visit in 1759:

Preached at Gainsborough, in Sir Neville Hickman’s Great Hall. …At two it was filled with a rude wild multitude (a few of the better spirit expected) yet all but two or three gentlemen were attentive, while I enforced our Lord’s words ‘What shall it profit a man if he shall gain the whole world and lose his own soul?’

Then, in 1790, the great hall was leased as a new theatre for the town. Extensive changes were made to the medieval space, with a stage erected where the dais had been, the walls lined with brightly painted theatre boxes and a gallery constructed at the west end. The range of performances included dramatic productions, musical entertainments, lectures and public ceremonies. Travelling companies provided much of the programming, a precarious existence which, as reports on the Gainsborough theatre show, was not always profitable.

Gainsborough Old Hall pictured from around 1892–1933, showing the view from the north-west with the kitchen in the foreground, the west range stacks to the right and the central range to the left, by CG Harper © Historic England Archive

Later History

Sir Henry Bacon (1788–1862) adopted the Hickman name in 1826 as a condition of his inheritance from his cousin Lady Frances Hickman (1747– 1826). For 20 years Sir Henry seems to have had little input into the building, save for occasional appearances at the theatre.

In 1848, however, he struck an agreement with the town to commission repairs and convert elements to create three new institutions: the Great Hall was cleared to make way for the town’s Corn Exchange, and the first floor of the east range was overhauled as grand Assembly Rooms, with premises for the Literary Institute in the room below. The restorations were carried out by Denzil Ibbetson, a railway engineer.

Newspaper articles across the 1850s and 60s list a busy schedule of lectures, performance, grand balls and soirées, as well as earnest discussion, and commerce. By 1890 the Corn exchange and Literary Institute had closed, and the Assembly room seems to have been much less used. Outside, the vestiges of the outer courtyard and Hall gardens were lost to encroaching residential housing. The east range was now leased as a Masonic lodge.

A photograph of the Steward’s Room at Gainsborough. In the 1950s this room was used to display artefacts of local history collected by the Friends of the Old Hall Association © Courtesy of the Friends of the Old Hall Association

In 1924 Hickman Beckett Bacon approached Sir Charles Peers at the Ministry of Works with an offer to place the Old Hall into the care of the state. That offer was declined, but Hickman’s nephew Sir Edmund Castell Bacon continued to work towards the long-term protection of the building. In 1949 he handed responsibility for the buildings to a new group, the Friends of the Old Hall Association (FOHA). Over the next two decades the FOHA, an entirely voluntary group, raised substantial funds to carry out extensive restoration work to the building, and opened the hall as a visitor attraction and community resource. In 1969 the Old Hall was transferred into the care of the state and is now managed by English Heritage.

Written by Kevin Booth